Actually, Romance Novel Print Sales are Down

...compared to romance print sales from the last 40 years

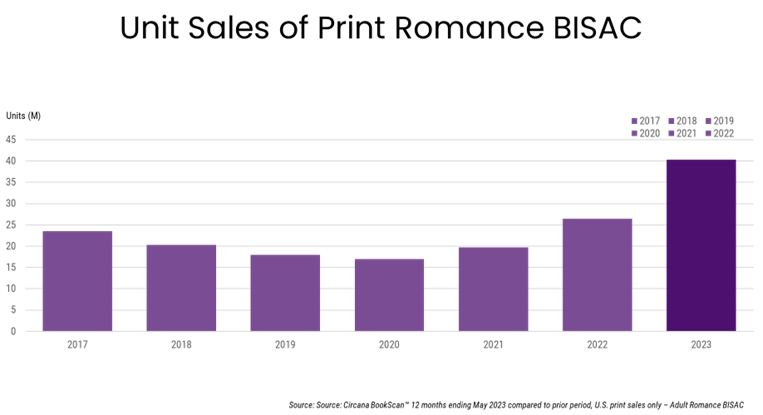

Romance print sales doubled from 18 million copies in 2020 to 39 million in 20231. Circana reported that romance unit sales were higher than they’d ever been since they started tracking the data in 2014. That’s amazing, right?! It seems to confirm a boom in interest in romance novels in recent years.

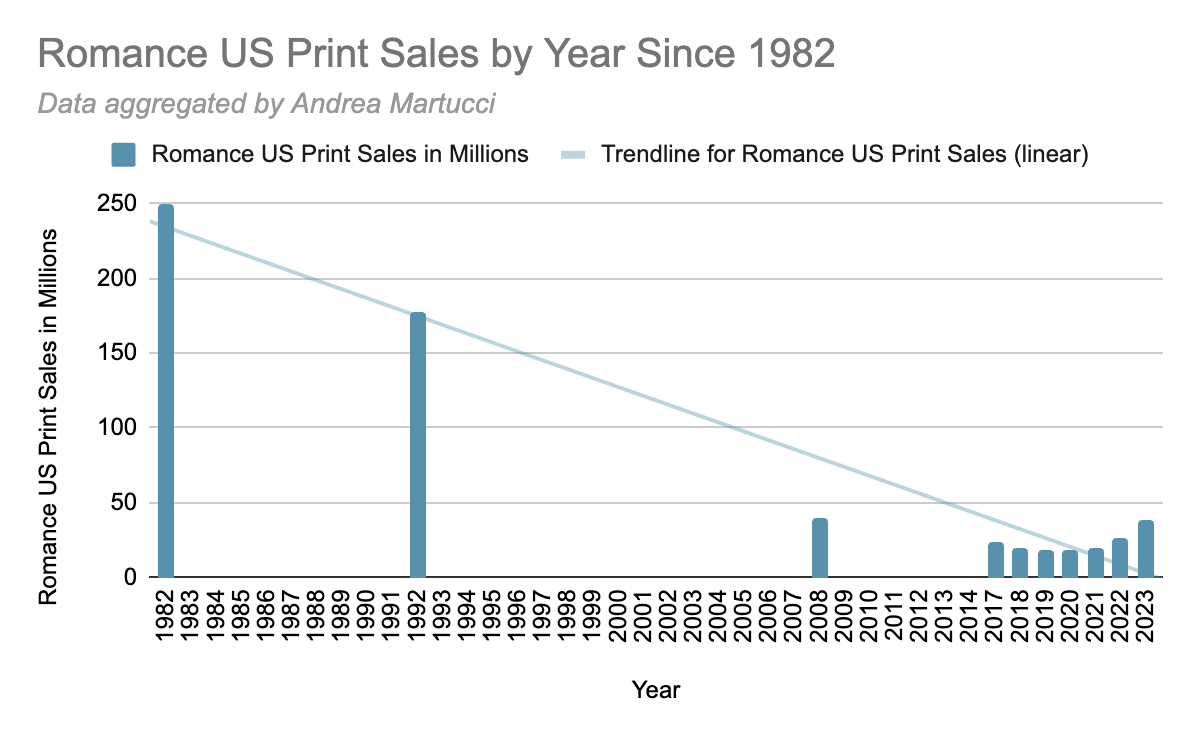

Except… if you look farther back in time, even just a little bit farther, data suggests that romance novel print sales are nowhere near where they used to be.

Today, I’d like to dispel the myth that romance in 2025 is bigger than it’s ever been before.

This is the latest in my Romance Data Mythbuster Series, which started with:

Quick note before we dive in — I will note throughout whether data describes print sales only vs. all units in any format, or if sales are US vs. worldwide. Before the 2000s, assume all data describes print only and represents all unit sales. At the end, I’ll address the digital revolution in romance.

1970s Best-Selling Romance Titles vs. 2020s Bestsellers

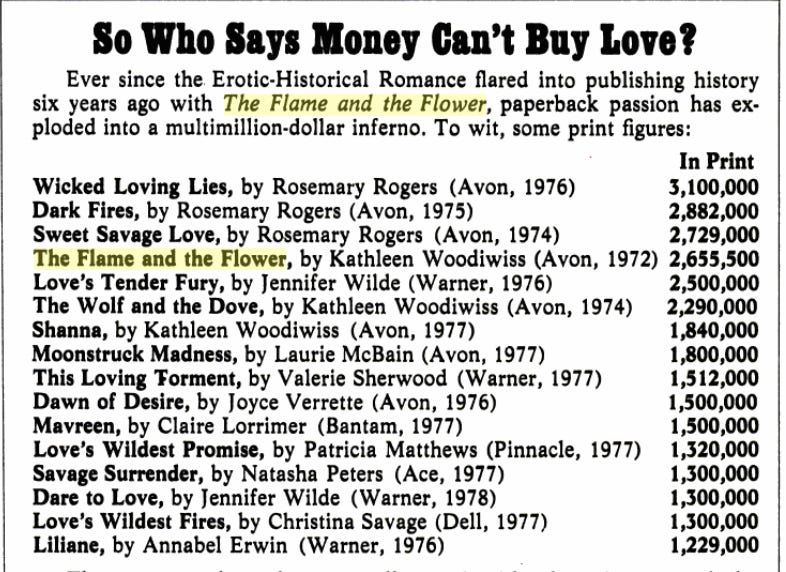

While erotic historical romance had a big moment in the 1970s, I’ve yet to find any data on the size of the entire romance genre at the time.2

However, it is instructive to compare sales of individual best-selling titles at the time to best-selling current romances, to get a sense of scale.

We do know that best-selling single-title paperback romance novels by authors like Kathleen Woodiwiss and Rosemary Rogers were selling between 1 to 3+ million copies each in the 1970s, making their total sales comparable to today’s bestselling authors like Sarah J. Maas (avg. 2.6 million copies over 15 books, likely in all formats) or Rebecca Yarros (avg. 2.6 million each over three Empyrean series books).

If you take into account that the US population is 63% higher today than in 1972, 1970s romance bestsellers would sell an equivalent 1.6 to 4.9 million copies each, if they penetrated the same proportion of the US population of available readers.3 That’s comparable to or higher than most of today’s bestselling romance titles. For example, current best-selling author Emily Henry’s 10 books have sold 9 million copies, averaging just under 1 million copies each.

This rough population inflation calculation still has 1970s romance bestsellers falling short of sales of recent break-out romance titles like It Ends with Us, by Colleen Hoover, which reportedly sold 10 million copies in all formats (worldwide), helped along by a film adaptation.

Never let it be said that I cherry pick data to fit my narrative — there are definitely a few examples of recent best-selling romance titles that blow 1970s numbers out of the water. Bear in mind, though, that these examples are the exception and not the rule: they are outliers that skew the overall picture.4

Conclusion: the most popular romance titles from the 1970s were selling fairly similar quantities compared with bestselling romance titles from the 2020s. It’s hard to say that the most popular romances today are significantly more popular than in the 1970s.

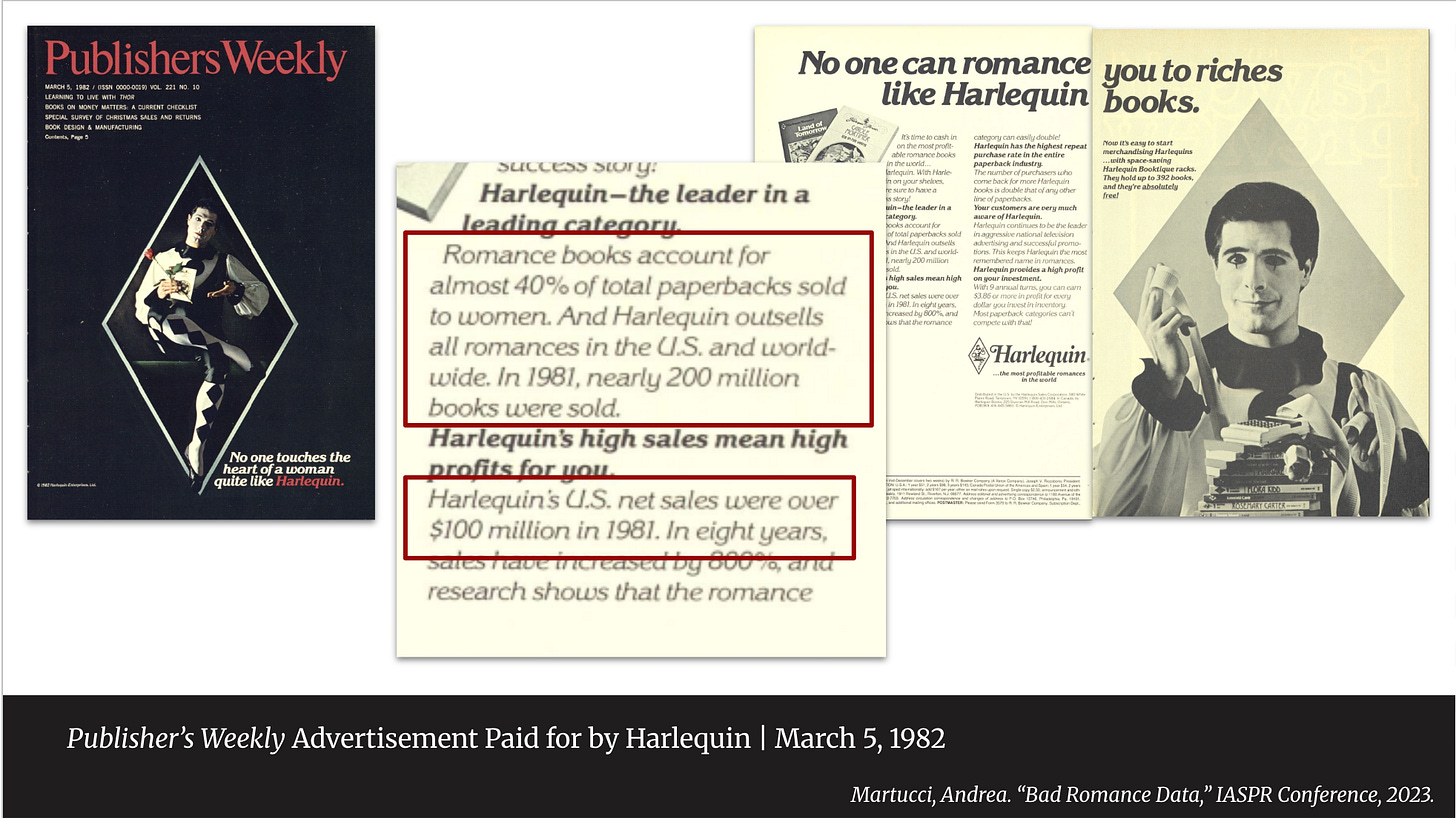

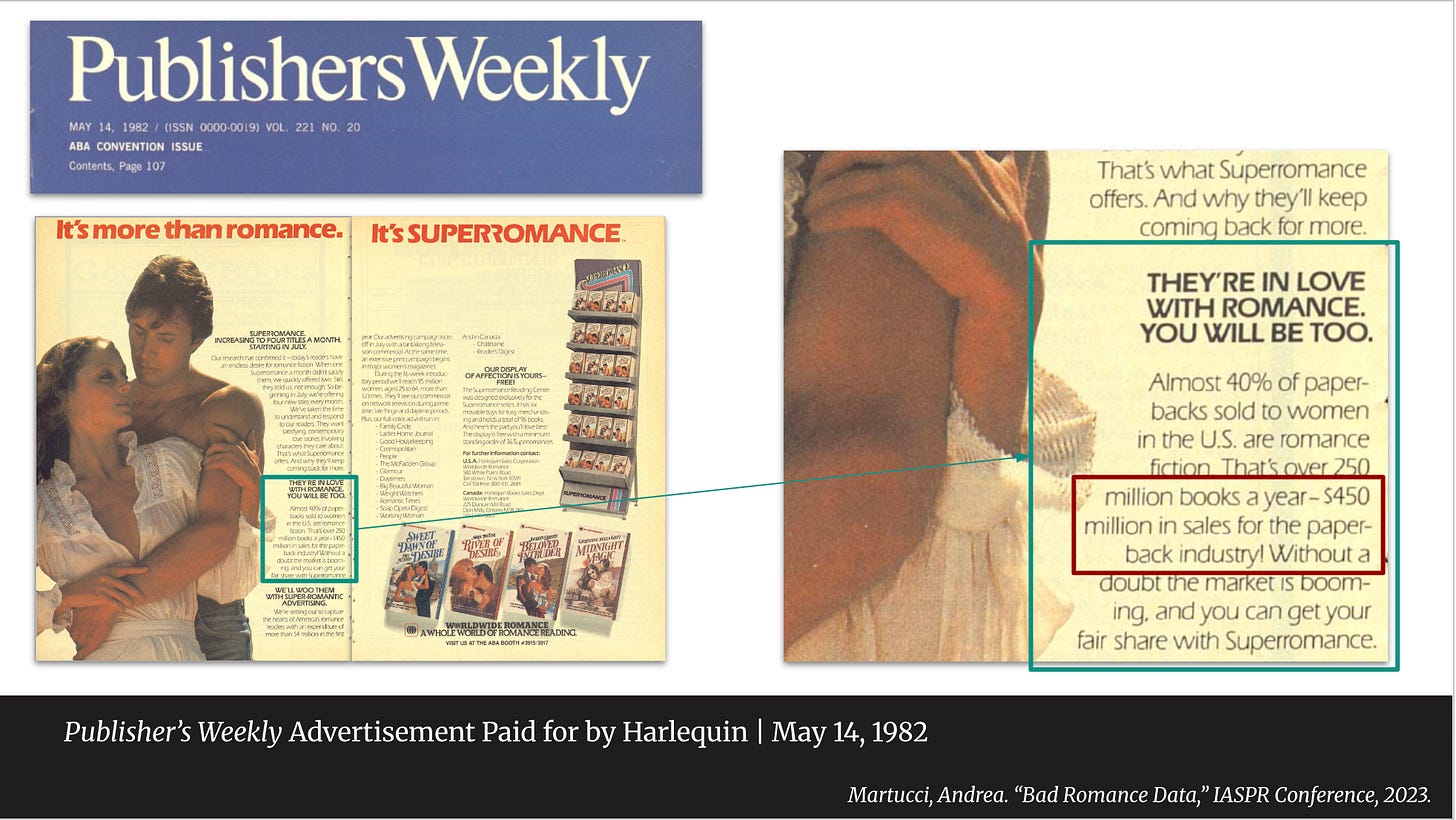

In the 1980s, Romance Boomed Bigly

In March 1982, Harlequin placed an ad in Publisher’s Weekly claiming that they sold nearly 200 million romances worldwide in 1981. Just 2 months later, another Harlequin ad was printed with the claim that romance fiction overall sold 250 million paperbacks a year in the United States alone.

If this was true, then the high of 39 million romance print sales in the US in ~2023 is barely 16% of romance print sales in 1982.

The proliferation of romance media and online discussion, romance bookstores, or romance community events in the 2020s are often cited as evidence of a current romance boom. Is this unique, in the grand scheme of romance history?

In the 1980s, the romance boom garnered much media attention, and publishers threw money at creating brand awareness for themselves and romance. This was also the era when romance professionalized — the Romance Writers of America organization was founded, media publications like Romantic Times sprung up to serve romance enthusiasts and editor Kathryn Falk became a Queen-maker in the industry. Independent bookstores that catered to romance readers, like Rainy Day Books in Kansas City, owned by Vivien Jennings, created robust local romance communities and also made influencers out of romance-friendly bookstore owners. Romance events like bookstore author signings and romance novel fan conventions had a moment, documented in 1987’s Where the Heart Roams documentary.

Conclusion: based on print sales data alone, the 1980s romance boom was over 6 times bigger than the current surge in popularity. Digital sales of romance and self-published romance sales in the 2020s would need to be 84% of the entire market for those avenues to make up the difference and enable today’s romance unit sales to match the 1980s, not even accounting for population growth.

1990s Romance: Echoes of the Boom

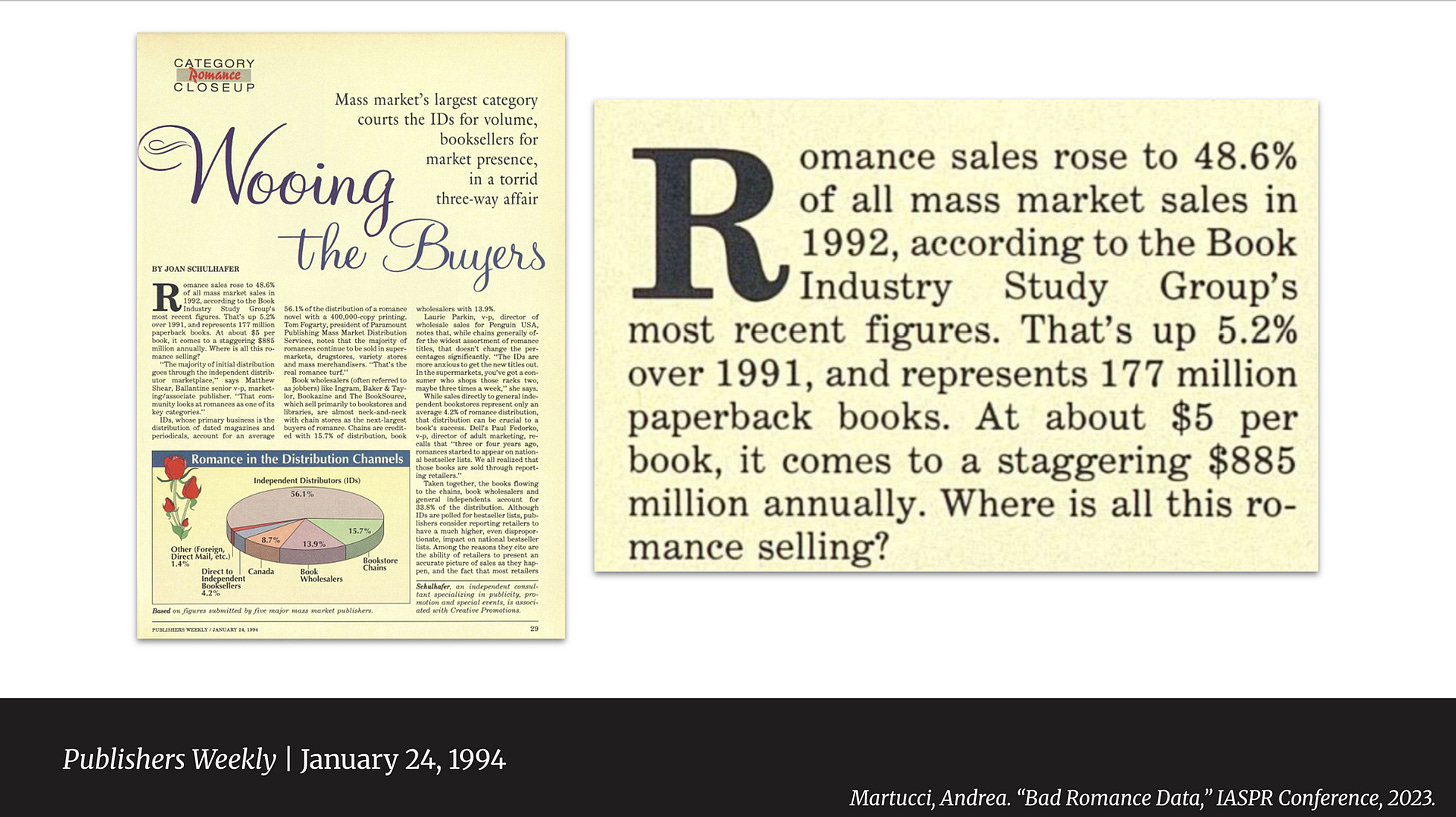

Let’s jump ahead a decade into the 1990s. An article about romance novel distribution from Publisher’s Weekly in 1994 extrapolated from Book Industry Study Group data that 177 million mass market paperback romances were sold in 1992.

If accurate, romance in the 1990s had declined 30% compared to the big 1980s boom. That’s pretty significant! And yet, 177 million paperback romances in 1992 is still 4.5x the size of 2023’s print romance market.

Conclusion: the print romance market in 2023 is just 22% of print romance sales in 1992.

2000s: Y2, Brute?

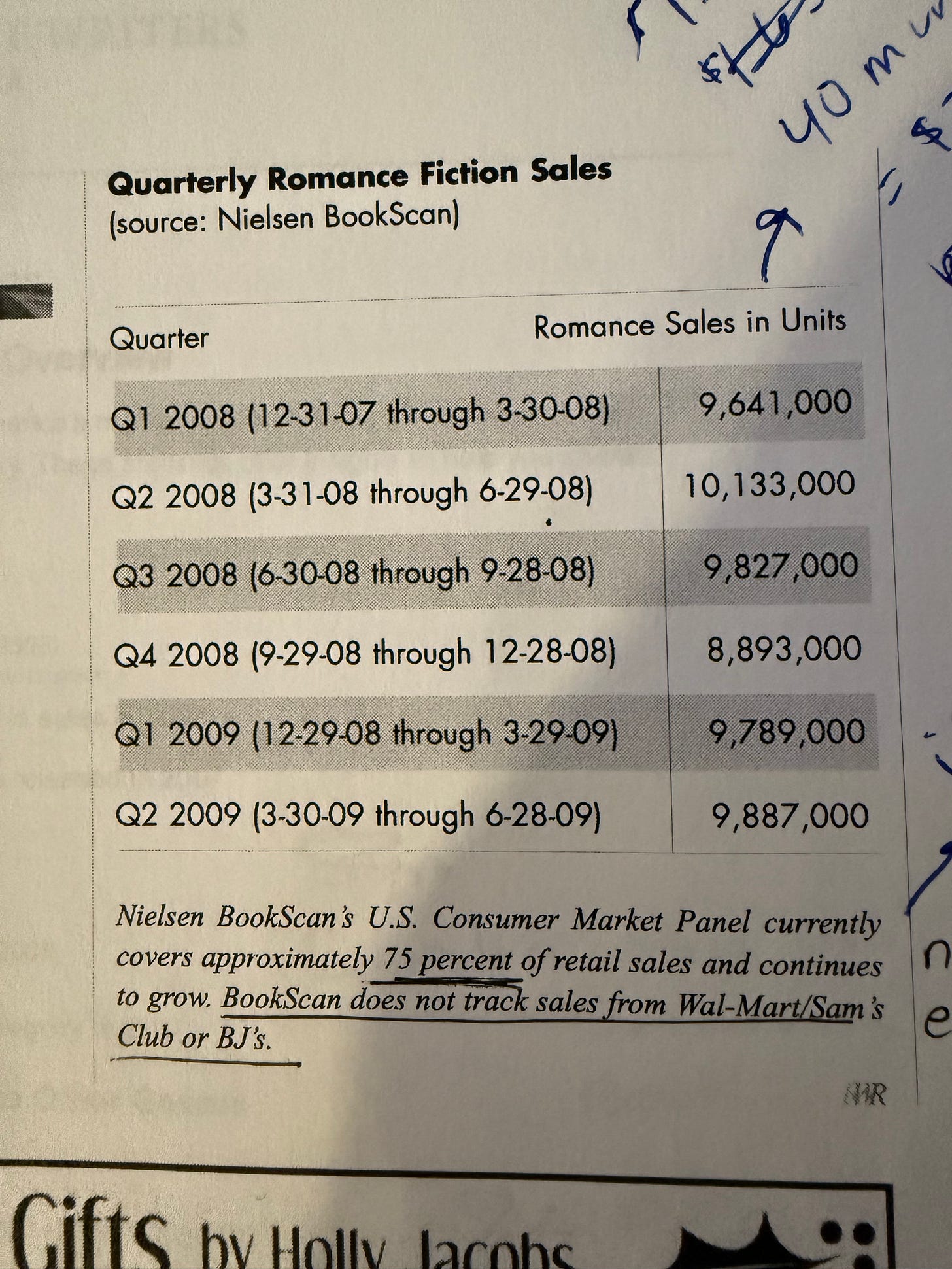

The 2000s were tumultuous for the publishing industry and the economy. I’ll bring in one available data point, reported in RWA’s 2009 RomStat report.

According to Nielsen BookScan data (Nielsen is now Circana, the source of most of today’s romance and book industry data), romance unit sales in 2008 were about 40 million.

That means romance dropped a whopping 137 million sales in the 16 years since 1992’s data, yet they were still 1 million units higher than today’s print sales of romance.

Conclusion: romance was not booming in 2008, compared to previous decades, but unit sales were still slightly higher than 2023 print sales.

2020s - a Romance Whimper

I mean, I think I’ve proven my point, but let’s get visual, because a picture paints a thousand words.

Here’s a nice bar chart from Circana, showing the current romance “boom.” Impressive recent growth!

Now, let’s zoom out a bit. I made this bar chart:

Is romance bigger than it’s ever been? Not if by “ever,” we go back farther than six years.

But What About Digital Romance Sales?!

Obviously, in 2025 you can buy a romance book in more formats than print, so maybe digital romance sales make a huge difference in the overall romance boom.

It’s possible! I certainly read lots of eBooks and audiobooks of traditionally-published romance, plus I read tons of self-published romance in digital formats. This brings me to three big complicating factors that make it really hard to compare historical romance data and today’s romance data.

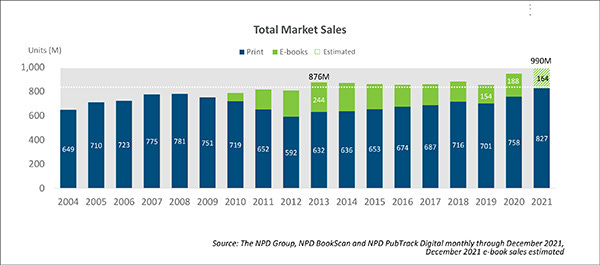

Print vs. Digital Trad Pub Sales

According to Nielsen’s data (now Circana), recent eBook sales of all books (not just romance) peaked in 2013, declining overall and as a proportion of overall unit sales since then. The 2020 data showed 188 million ebooks sold, ~20% of all units sold that year. I’m assuming this data is largely or entirely representing traditionally-published books as NPD PubTrack Digital reported on retail data, including Amazon, but I don’t think it includes self-published ebooks.5

Anecdotally, it seems like romance readers are more likely to consume their books digitally compared with format choice for other types of books, so maybe the proportion of romance sold digitally is higher than 20%. Maybe!

But even if 50% of traditionally-published romance sales were digital, at best that would bring trad pub romance unit sales to 78 million — still far below 1980s and 1990s numbers.

What About Self-Published Romance?

To this, I must throw my hands up in the air and say that really, we have no idea. Nobody has any idea how much self-published romance is selling every year, except for Amazon, and believe me, they are not sharing that data.

What About New Romance Content Formats?

Lots of content we’d consider “romance novels” is consumed via subscription- or coin-based platforms like Wattpad and Radish, as well as Kindle Unlimited, which counts consumption as page reads, not books sold.

Again — this is essentially impossible to understand via publicly-available data. The technology platforms own this data. I will preserve my sanity and not attempt to explain it.

Are Romance Novels Bigger Than They’ve Ever Been Before?

Probably not!

Romance print sales are bigger now than they have been in the last 20 years, however in the historical sense, the current surge in public interest and engagement with romance novels is not representative of the biggest romance boom the US has ever experienced.

This is, arguably, a romance novel podcast/Substack, so my point here isn’t to hate on romance — it’s to remind you, me, journalists, the romance curious, and the old-time romance fans, that romance novels, their history, and the data about them, is a bit more nuanced than it may seem at first glance.

I obviously think it’s important to contextualize what’s happening in romance now in the wider history of time and the genre — it’s kind of what I do here. Engaging with the romance booms and busts of the past can help us better understand why the romance novel genre and its readers are so interesting, and also help us meaningfully interpret the narratives spun about romance and its readers and their function, when they differ from reality.

This is from a NYT article, although they don’t cite the source of the information. This is similar enough to other data I’ve seen from Circana, so I trust it to the degree that I trust any of this information, and also assume Circana was the source: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/07/07/briefing/romance-bookstores.html?smid=url-share

This is at least in part because the sweet contemporary category romances of the time, primarily distributed in North America by Harlequin and by Mills and Boon elsewhere, was not necessarily seen in many people’s minds as being the same genre as the erotic historical romances. The 1970s boom in more sexually adventurous stories laid the foundation for the 1980s sexy contemporary category romance boom, which also led to the professionalization of the romance writer, and reasons for many to put clearer boundaries around the romance genre.

For context, the US population was 209 million in 1972, and is currently 340 million in 2023 — a 63% increase.

I could speculate about why the environment in 2020s enables massive bestsellers to a greater degree than in the 1970s, but it’s a bit off topic.

It’s hard to find data on this — if anyone can point me to a reliable source explaining what Circana does/does not include, I’d appreciate it!

Fascinating context—thank you for digging into all these historical sources.

I can help explain Circana/NPD/Nielsen PubTrack Digital figures: When they report ebook or digital sales, that's coming from publishers' own reporting and not retail or through-the-register sales like print books. So that graph you have does not reflect the self-pub sales on the ebook/digital side. They've never been able to capture the self-pub market except for its print retail sales.

Great post! Thank you for sharing this historical data. I’m continually shocked by how little data is available about book sales beyond the dribs and drabs that Circana chooses to share.

I did a poll on my Instagram (which targets romance readers) about primary reading format and 63% said ebook, so I think romance readers likely do consume more ebooks. But not enough to explain the significant drop. (Romance readers also appear to be big library borrowers too).