Why is Fourth Wing so popular now? Why was Fifty Shades of Grey so popular a decade ago? Why was The Flame and the Flower a New York Times bestseller in the 1970s?

These books have all inspired trend pieces in their own time that point to the popularity of these particular books signaling something important about the romantic tastes of the masses.

They’ve also all been touted as starting and popularizing new subgenres of romance: Romantasy (aka Spicy Books), BDSM Romance (Mommy Porn), and Historical Romance (Bodice Rippers).

At every turn, the bewildered journalists ask:

Why is this book popular?

The less nuanced takes conclude that “sex” is the answer to “why is this popular,” and the derisive monikers given to the subgenres reflect that. But let’s be honest: outsiders always flatten the appeal of popular romance fiction down to “sex.”

Even inside the genre, romance readers also ask the same question, but perhaps put the emphasis in a different place:

Why is this book popular?

Do Best-Selling Romance Novels Represent Romance?

Mass media platforms tend to take the singular example and attempt to make generalizations about the whole of a genre. “Fifty Shades is popular, and it’s a romance, therefore: the reason Fifty Shades is popular (if we can figure it out) is also the reason why romance novels are popular.”

Within the romance genre, though, I think romance readers are trying to understand why this book has achieved a level of popularity outside the regular audience of romance readers, especially when we can often identify other authors and books that seem to do the same things but better.

Back in 2012, for example, Sarah Wendell of Smart Bitches, Trashy Books was interviewed by the LA Times about the popularity of Fifty Shades:

Wendell, an enthusiastic romance reader, didn’t think much of ‘Fifty Shades of Grey’ when she read it in November. ‘I found it to be melancholy and meandering, and the heroine narrator is so maudlin and wimpy I grew more and more irritated with her and with the story and had to stop.’1

Wendell does also offer some thoughts on why it’s popular, offering the secret world element (BDSM scene), the similarity of Christian to “old skool romance heroes,” and the deep first-person point of view.

Recently I spoke with Sarah Skilton on the podcast about Fourth Wing2. I think we both enjoyed reading it more than Wendell seemed to enjoy Fifty Shades, and experienced firsthand how the breathless pace created a compelling read. This is to say: we could acknowledge the appeal.

Did we spend 20+ minutes trying to make sense of one framing choice on page 1? Yes. Yes, we did. And yeah, ultimately we concluded that “it’s just not that deep,” and moved on.

It’s just not that sexy or romantic compared with other romance we’ve read and the world building is flat compared with other fantasy or romantic fantasy we’ve read.

So why is this book popular? Sarah Skilton’s hypothesis:

It's commercial enough that people who don't read either [romantasy or fantasy] can pick it up and not feel like they're adrift and feel like they have to be a “romantic reader” or a “fantasy reader” to enjoy it, and that's partially why it's so popular.

I think Sarah’s theory begs the question: is Fourth Wing a popular romance despite not being a great representation of romance, or because it’s not a great representation of romance?

To achieve a level of ubiquitous popularity, the kind that is remarked upon and written about in every major media publication, something must be accessible to the masses. For the most popular romances to be legible to the average consumer, the text can’t rely on a reader’s genre competence — therefore, it must assume the reader has none.

It’s ironic that romance novels, which are often derided as populist drivel, are actually not populist enough to be familiar to The New York Times audience.

Does Popularity Last? Let’s Look to the Past…

Recently, I reviewed most of the New York Times Bestsellers lists from the 1970s. I was trying to see something: does popularity last?

How come I couldn’t name more romance novelists with popular books from the 1970s?

I knew that Kathleen Woodiwiss’s The Flame and the Flower, published by Avon in 1972, was a huge bestseller and kicked off the American erotic historical romance boom in the 1970s. I read Woodiwiss’s catalog in the early 2000s when I was a teen haunting used book sales. Her books popularized the one man/one woman heterosexual pairing that has dominated the genre since then.

(Modern readers who are newer to the genre and familiar with the current norms may be surprised to learn that sexier adventure-focused historical epics from before and after this time frequently depicted heroines engaged in both both violent and consensual sexual encounters with many men other than her eventual mate. This is understood as a total no-no today: you decide if this is progress.3)

I knew that Rosemary Rogers followed closely behind with her “sweet/savage” strain of romances, bucking the one man/one woman trend. I never read her books but knew of her since I’ve become a part-time romance scholar.

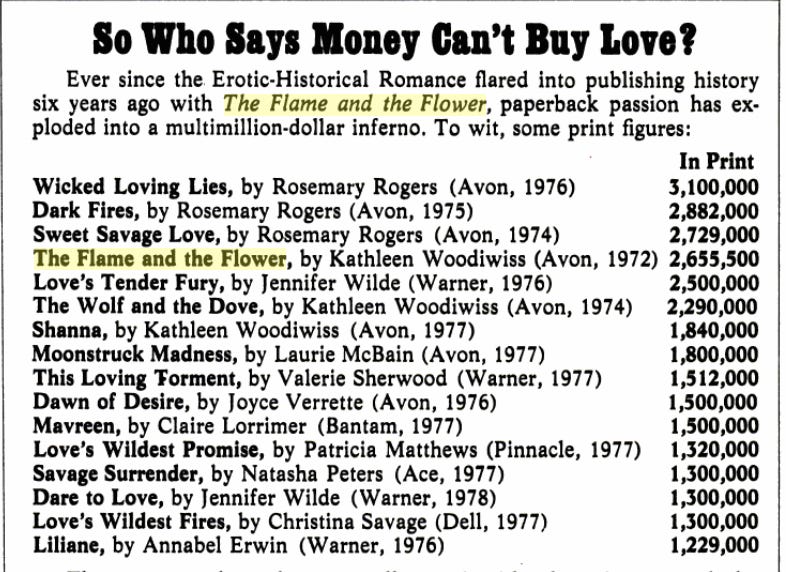

In 1978, New York Magazine published a 2-page spread on romance with a sidebar calling out books in print for top-selling historical romance authors at the time. Rosemary Rogers tops the list, although Woodiwiss is well-represented with multiple titles on the list. At least I recognize Patricia Matthews and Jennifer Wilde, and I’ve recently stumbled on Laurie McBain when reviewing the NYT lists from the ‘70s.

While Rosemary Rogers’s books outsold even Woodiwiss in the 1970s, in the long run the “sweet/savage” strain died out and the dominant mode followed in Woodiwiss’s image.

As Carol M. Thurston wrote in The Romance Revolution (published 1987):

By the late 1970s, the macho stud patterned after Rosemary Rogers’s Steve Morgan — inarticulate and unknowable, demanding, cruel, even sadistic — had begun to fall out of favor, and by 1980 he was more often than not the villain in the piece. (page 72)

Perhaps many of these other titles and authors that I wasn’t super familiar with were similar: they were hot, hot, hot for a period but didn’t get incorporated into the genre’s memory because they were on the wrong side of the longer-term trend?

From reading sources from the 1980s, it seems that it didn’t even take 50 years for some of these authors to fade from the popular memory within romance and outside of it: less than a decade was sufficient.

Woodiwiss was named a favorite author by 27% of the [502] readers surveyed in 1982 and by 23% in 1985…. Patricia Matthews, a multimillion-copy seller during the 1970s who is still writing today, was listed as a favorite by only one reader, and Jennifer Wilde (a pseudonym for Tom Huff), also a bestselling author during the 1970s and still writing, was named by three.

The Romance Revolution by Carol M. Thurston (page 171)

Does popularity last? It seems that being a bestselling author, within and beyond the romance genre, isn’t a guarantee that you’ll make a lasting impression.

Woodiwiss’s books broke the mold at the time, influencing the direction of the romance genre for decades (whether you like it or not). She’s left a legacy.

Is Woodiwiss known outside of the audience of romance readers who have a sense of genre history? I am learning…no.

Anecdotally, I had a question in my Boston LitCrawl event Who is Fabio: Romance Novel Jeopardy about Woodiwiss and nobody knew the answer except for one die-hard romance reader in the audience. The very sweet group of early 20-something contestants came up to me after the game and I asked them if they read romance. “Like Colleen Hoover?,” they asked.

Final Thoughts

The relative scale of popularity with my three bestselling examples varies quite a bit.

This is one of those Substack essays where I leave you with more questions than answers. I’m not even going to pretend to bring this home with a rousing conclusion. Byeeeeeeee

This text in the LA Times article seems to be borrowed from a post on the Smart Bitches site: https://smartbitchestrashybooks.com/2012/03/50-shades-of-grey-why-is-it-so-increasingly-popular/

“You have a podcast?!” https://shelflovepodcast.com/episodes/season-2/episode-160/romantasy-fourth-wing-with-sarah-skilton

Regencies were decidedly chaste (and category length) up to 1979, when Catherine Coulter debuted on-page sex scenes with The Rebel Bride paving the way for today’s standalone full-length sexy Regencies from authors like Julia Quinn, Tessa Dare, and Lisa Kleypas.

Actually lower, if you combine the sales of any two of Woodiwiss’s books on the list to compare with Yarros’s 2 books in the series.

Time reports 2 million copies in 2023 (https://time.com/6332608/iron-flame-rebecca-yarros/), while Publishers’ Weekly reports another 1.1 million copies in the first half of 2024 (https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/financial-reporting/article/95444-with-fantasy-on-fire-print-book-sales-are-catching-up-to-2023.html).

I was just having a very similar conversation with Vicky, Charlotte, and Hannah on Saturday while we discussed our most recent Romance History Project selection, Playing the Odds by Nora Roberts. None of us liked it, to put it mildly. But it was Nora's first bestseller and she's basically been a bestseller ever since. So clearly readers were responding to something in that book! We all wish we knew more about what else was popular at that time.

On the other hand, I keep going back to how I feel about today's bestsellers, most of which are not my cup of tea. They seem more for people who don't read all that much and maybe don't know that other, better books exist. (I feel so snobby saying this!) The page-turner element and simpler prose has to be a large part of the appeal, whether we're discussing Nora Roberts, SJM, or Colleen Hoover.

This is an awesome post. This line will stay with me for a long time. "It’s ironic that romance novels, which are often derided as populist drivel, are actually not populist enough to be familiar to The New York Times audience." So true!!!!!!