We can likely thank social media censorship for the term “spicy books.”

Platforms like TikTok, Instagram, and Twitter use secretive algorithms and filters, and, occasionally, stated policies and terms of service, to influence what we talk about, but it really just ends up shaping how we talk about them.

For example, content creators will replace “sex” with “seggs” in captions on Instagram or Tiktok to prevent their content from being suppressed or replace words with emojis (hello 🍆 ) or replace letters with symbols (le$bian).

Clock app (TikTok). Panini (pandemic). Unalive (kill). B00bs (boobs). 🌽 (porn).

Ever wonder why dark romance promotions are riddled with misspellings, emojis, euphemisms, and intentional malapropisms?

Part of me wonders if this Substack post will be suppressed by your email services or in Google search results, which I opposite of love (hate).

Literally Can’t Say That

A 2022 article in The Washington Post called this “internet algospeak,” and notes that getting around moderators is a tradition as old as the internet, and heck, even predates the internet. After all, “oh my goodness” is just a way to say “oh my god” without angering parents or religious figures who forbid “using the lord’s name in vain” — our speech has always been moderated by powerful forces in the communities we live in.

“‘…it leads to collateral damage of literal speech.’ Attempting to regulate human speech at a scale of billions of people in dozens of different languages and trying to contend with things such as humor, sarcasm, local context and slang can’t be done by simply down-ranking certain words, [Evan] Greer argues.”

Internet ‘algospeak’ is changing our language in real time, from ‘nip nops’ to ‘le dollar bean’ by Taylor Lorenz, The Washington Post

Like, it’s literally a problem that when leveraging the awesome power of the internet to broadcast messages that we can’t just say what we mean.

There’s a lot to talk about with this topic — the article above discusses how discussing violence against marginalized people or even sharing health education involving body parts creates issues when creators have to use ridiculous and vague words to even have a chance of getting their message out.

My beat is romance novels though, so today I’m going to focus on how “algospeak” is impacting romance novel discourse inside and outside the community.

The Rise of Spicy Books

Have you noticed people online and in real life calling romance novels “spicy books”? Perhaps you noticed the discourse increasingly talking about “spice level” or using the hot pepper emoji to discuss “steam” level: for example, books may be 🌶️ or they may be 🌶️🌶️🌶️🌶️🌶️ 🔥 🥵.

In the old days, we used to be able to talk about how “sexy” books were, but in algospeak terms, the issue with using “sexy” is that the word contains “sex.” Sooner than you could sing “Let’s not talk about sex, baby,” creators learned that “sexy” was out, and spicy was subbed in.

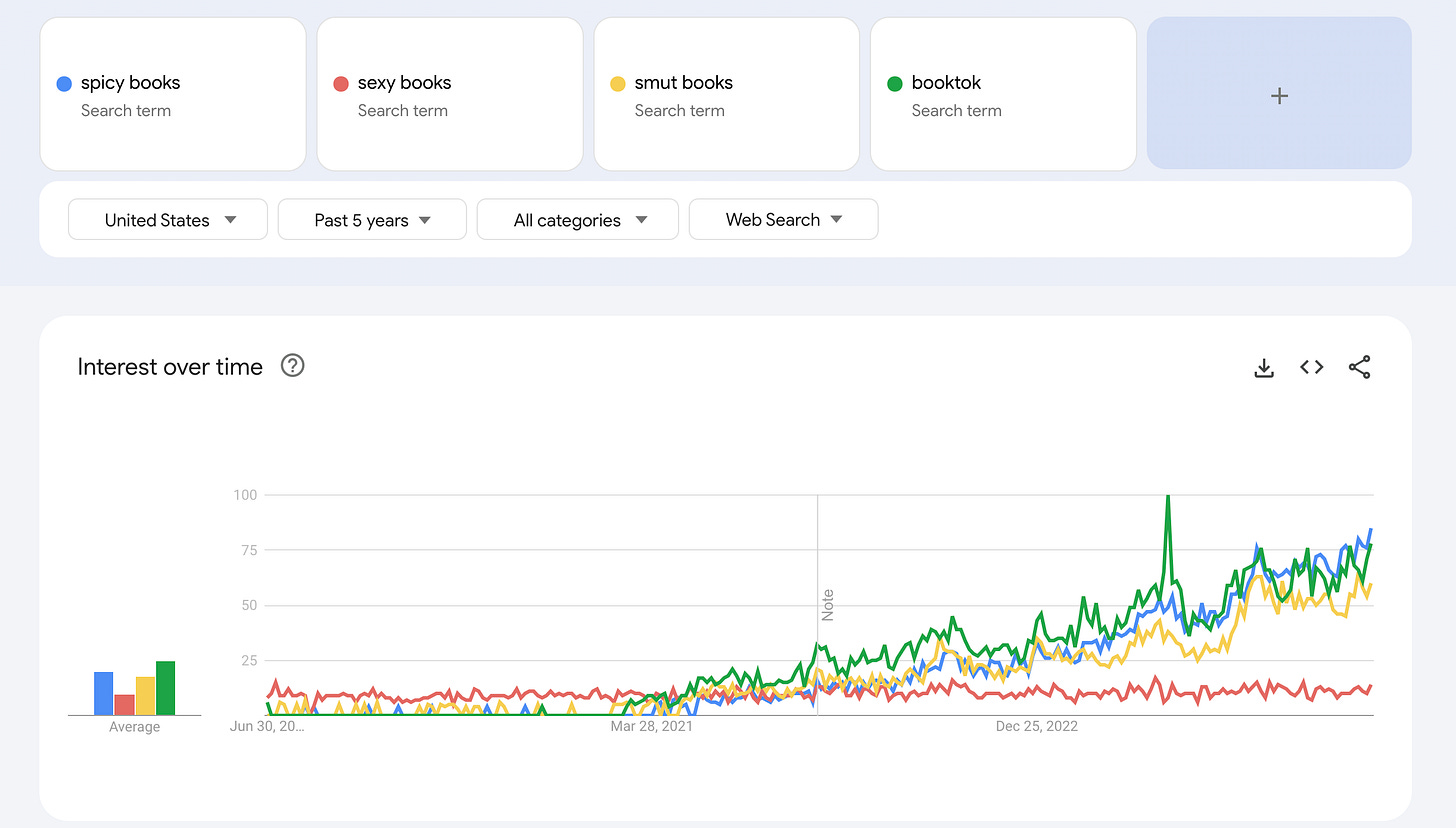

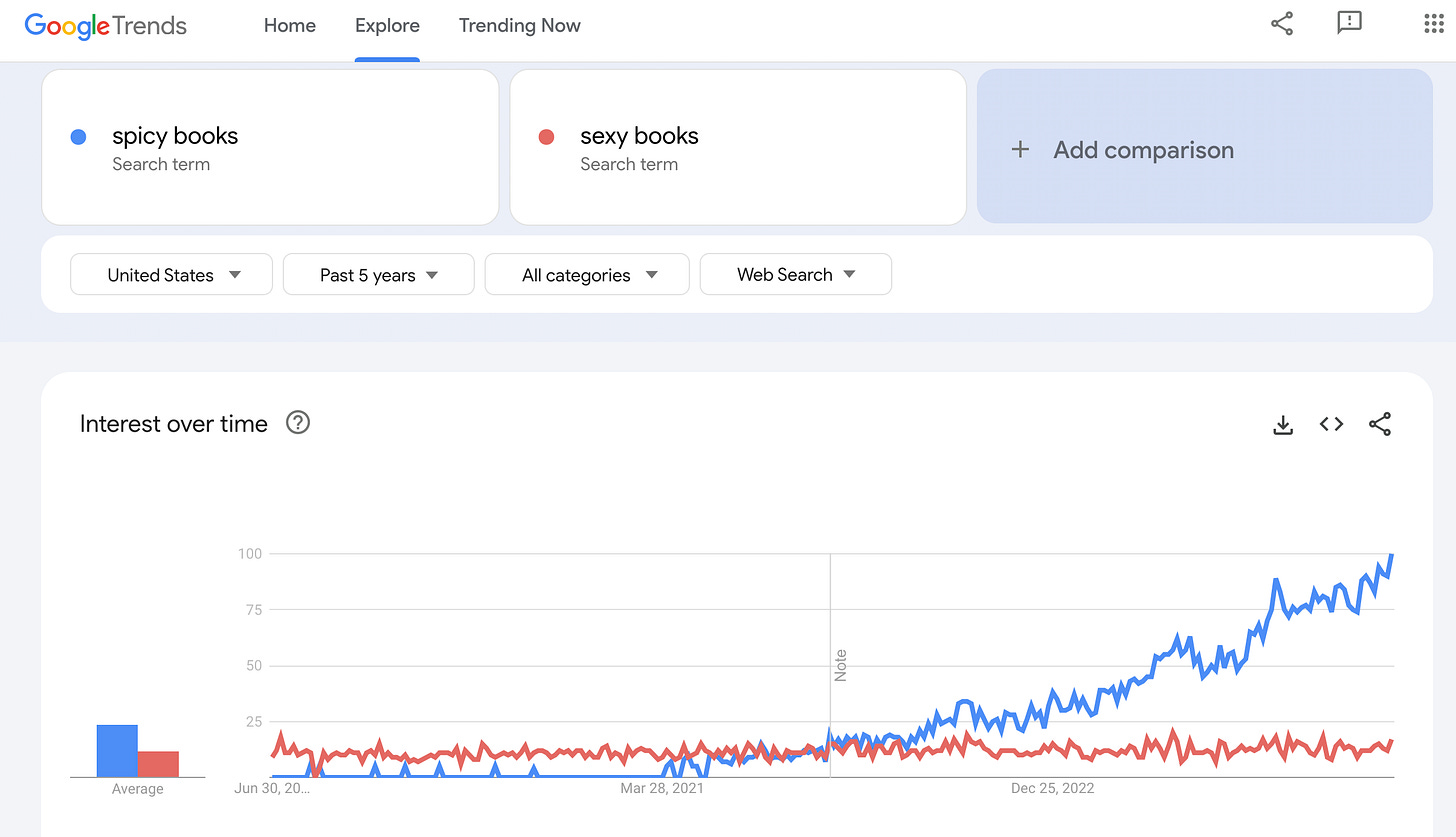

Using Google Trends1, we can see that in the past 5 years, the term “sexy books” has remained fairly stable as a web search term, however “spicy books” and “smut books” have risen from significantly less usage prior to 2021 compared with today, to being significantly more popular than “sexy books” in 2024 — following a similar trajectory with the term “booktok.”

According to Google Trends web search trends, “spicy books” as a term is the most popular it’s ever been, while “sexy books” is used only 18% as frequently in comparison.

My hypothesis is that greater usage of “spicy books” on TikTok, Instagram, etc. started bleeding into the lexicon of those platform users, which then started to impact other behaviors such as how they search for information on Google.2

Spicy Books Are In the Eye of the Beholder

The issue I have with the term “spicy books” is that it doesn’t actually seem to mean anything.

To be fair, the term “sexy book” has the same issue, if used as a descriptor — what an individual considers “sexy” is subjective, after all.

Perhaps my issue is that “spicy book” is being used to signify “romance novel,” instead of being used as a descriptor for a type of book or type of romance novel.

When “spicy book” starts to stand in for all romance novels, the descriptor of “spicy” becomes meaningless. It also creates a massive misunderstanding about what a “romance novel” is, for readers and non-readers alike.

For non-readers of romance novels, they may assume that the broad term “spicy book” to signify “romance novel” indicates that the genre, by definition, requires that a book be sexy. This isn’t the case, and flattens the genre into the stereotype that romance readers have been chafing at for decades, if not centuries.3

It reminds me of how grating it is when all romance novels from the 1980s are called “bodice rippers,” not because I don’t love bodice rippers but because bodice rippers are one very specific type of romance novel and there are many more romance novels, even from the 1980s, that are NOT bodice rippers.

For readers of romance, “spicy book” flattens our ability to have meaningful conversations about an aspect of romance novels that are helpful for finding the books we individually want to read. It impairs our ability to communicate information clearly — and that’s weird, because the romance community loves creating and debating the meaning of in-community lingo.

Creating and Debating Meaning in Community

Forming and debating in-community language to define the nuances of the books we read is a time-honored past-time for romance readers (and I imagine this is similar for other types of fan communities).

Genres seek categorization when describing their whole or their parts — think romance vs. women’s fiction (genre classifications), enemies to lovers vs. friends to lovers (tropes), and cinnamon roll vs. himbo4 (archetypes). Genres are by their very nature the result of artificially-created (and enforced) boundaries, and the categories serve to create a shared language and understanding that enables communication.

For example, nothing gets romance readers more heated than debating “heat ratings” — that is, trying to create a scale of sexual explicitness in romance novels. It’s just too subjective to ever nail down, however I think there’s much to be gained by having the conversation. In the process, individuals need to provide examples to contextualize chosen words or categories.

For example, All About Romance has been reviewing romance for decades, and has a “sensuality rating system” with definitions.

You may not agree with this, but at least there’s an attempt to articulate the difference between “Warm” and “Hot.”

Warm: Moderately explicit sensuality. Physical details are described, but are not graphically depicted. Much is left to the reader’s imagination.

Hot: More explicit sensuality. Sex is described in more graphic terms. Hot books typically have more sex scenes and are more likely to depict acts beyond intercourse.

-All About Romance, Sensuality Rating System (excerpt)

Using the above excerpted definitions, two romance readers could have a productive discussion where they make the case for a book being Warm vs. Hot. Close reading could provide evidence making a case for one or the other.

Should Words Mean Things?

Why does specificity with words, particularly those that seek to categorize, matter?

Those with first-hand experience with the romance genre and some sense of its breadth have traditionally acknowledged that there is a difference between romance novels and erotica, and between erotica and 🌽ography.

I appreciate discussing and understanding the distinctions because they help me understand the differentiating characteristics, and even more importantly, how those characteristics impact how these genres are received and used by consumers.

At the same time, I have zero patience for people who want to turn these genre classifications, particularly between romance novels and 🌽ography, into a value judgement or a spectrum of respectability.

Nonetheless, these classifications do mean something, and there are practical uses. Let me return to the term “spicy books,” which I believe is standing in for “romance novel” in current discourse.

If one discusses “spicy books” vaguely because they’re not actually allowed to say what they mean (thanks to social media algorithms/censorship), and then everyone starts repeating the word without it having a clear meaning, then we are looking at simulacra of the third order — the phrase is a copy of a copy of a copy with no original. The difference between a “spicy book” and a spicy book is meaningless — there is no difference between reality and representation.5

“Spicy books” flattens an entire genre, purporting to mean something while meaning nothing at all. Books with two gauzily described sex scenes are “spicy books” along with ones where the characters kiss once at the end, and others where the exchange of bodily fluids is creative, pervasive, and narrated by explicit dirty talk, as well as books that aren’t romance novels at all.

I would argue that the squishiness of terms allows alarmist bad actors to invoke the most exaggerated and extreme specter of a thing to characterize a broad swath of content, from the blatantly unobjectionable up to content that could reasonably warrant discussion before being exposed to certain audiences.

The dissolution of meaning enables a straight line to alarmist headlines that conflate “‘spicy’ adult fiction” with “erotic titles” that are corrupting children.

In the image above, the TikTok creator is holding “The Love Hypothesis” by Ali Hazelwood. I’m happy for anyone who enjoyed the sex scenes in this book, but filing this book under the literal subhead “erotic” is gross mischaracterization.

Guardian writers are responsible for their own shoddy reporting, of course, but these misunderstandings in meaning proliferate when The Love Hypothesis is lumped under the same hashtag as Delta of Venus.6

In this way, “spicy books” doesn’t just stand in for all romance novels, it also starts to include “erotic titles” and bad actors can further distort meaning by invoking “🌽ography,” which is often regulated by governments with minimum age restrictions, such as requiring consumers to be legal adults.

The direct result of this is imposing overzealous and badly-informed restrictions on accessing content. As an example, from the above Guardian article:

On the Waterstones online listing of Icebreaker, the first in Grace’s Maple Hill Series, the first review is by one of the shop’s booksellers and says that the novel is a “Spicy romance for readers 18+”.

In this example, we see a romance novel being implicitly categorized as 🌽ography, as indicated by the “readers 18+” note. Icebreaker may include sexually-explicit content, but that doesn’t make it 🌽ography — yet, this slippage seems closely related to the imprecise application and understanding of the term “spicy books.”

Look — the pearl clutching around “the children” consuming romance isn’t anything new. It would be exhausting to even attempt to trace it back or detail notable instances from the last decades. I’m not blaming TikTok, or that one bookseller at Waterstones, or even the author of The Guardian article.

I’m just saying — “spicy books” doesn’t mean anything, you know what I mean?

Google Trends data represent “interest over time” and all of the data is relative to the other data. Google Trends explains is like this: “Interest over time. Numbers represent search interest relative to the highest point on the chart for the given region and time. A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term. A value of 50 means that the term is half as popular. A score of 0 means there was not enough data for this term.”

Google Trends is helpful because it can show us how term popularity has changed over time in Google web searches, but it doesn’t show correlation or causation linked to usage or popularity on the social media platforms. The Google Trends data doesn’t show correlation, but it does indicate that the term “spicy books” has rapidly gained significantly greater usage, especially compared with “sexy books,” which remained flat.

I think the issue is less that the stereotype assumes that all romance novels are sexually explicit — some are, and that doesn’t make them lesser than as a form of entertainment. The issue with a stereotype is the flattening — it refuses to acknowledge the beautiful variety that is found within romance, while also shunting aside the aspects that actually do differentiate it from other genres or forms of entertainment.

I really enjoyed this Smut Report episode about Himbos. The way Erin, Holly, and Ingrid break down the archetype is fun, leads to a greater understanding of what the archetype is, why it works, and what it’s NOT. https://smutreport.com/2023/06/16/lets-talk-archetypes-himbospodcast-edition/

Invoking Baudrillard here, as I am wont to do.

If you want to hear Jodie Slaughter and I talk about how Delta of Venus by Anais Nin is both deeply unerotic, effed up, disturbing, and weird, then boy howdy do I have the episode for you…

“Perhaps my issue is that “spicy book” is being used to signify “romance novel,” instead of being used as a descriptor for a type of book or type of romance novel.”

100%! Not all of us write spice or even steam so people pick up romance novels expecting them all to burst into flame by chapter 2. The tantrum when a book “isn’t spicy” or “isn’t spicy enough” is insulting.

Great topic, Andrea.

This post makes me want to review my social media posts for the words you mentioned and compare the reach of those posts to others.

In general, our culture (U.S.) seems to struggle with nuance. Plus, many people cannot handle [content featuring] love and other intense emotions. And the dreaded S-word? Heck no! (Unless, of course, it’s a “forced entry” aka non-consensual 🍆 scene in a literary novel or movie. Then, somehow, it’s considered brilliant.)

I wonder how much of the fear around spice/heat/love/seggs is thinly masked fear of 👯♀️🙋🏻♀️💁🏻♀️💃🏻 empowerment?

Throughout history, marginalized groups have found ways to communicate in code.

But now mainstream media is catching on to the appeal of romance novels and trying to contribute to the conversation. One problem is that so many media pros don’t know the definition of a romance novel and confuse it with a romantic novel or with 🌽.