“Often father and daughter look down on mother (woman) together. They exchange meaningful glances when she misses a point. They agree that she is not bright as they are, cannot reason as they do. This collusion does not save the daughter from the mother’s fate.”

― Bonnie Burstow, Radical Feminist Therapy: Working in the Context of Violence

A few years ago, I bought a “Votes for Women” teapot in Newport, Rhode Island, after visiting the Marble House — the Mansion where Alva Vanderbilt held a 1909 women’s suffrage rally.

My family uses this teapot almost every day, as we like to have tea together after dinner. When I first got this teapot in 2023, it was quaint, a daily reminder of how far we’ve come. Women couldn’t just vote: they ran for president. Now, in 2025, it feels like a more serious warning that progress is not linear and that gains can be lost much more easily than they were won. Women can run for president, but it’s still inconceivable for many that they have the right to win the race.

How quickly our perception of things can change.

The Newport mansions themselves are a physical reminder of oligarchs who once ruled from palaces on the sea only to discover that they could not sustain their position on top of the world. For each Marble Palace that was preserved for today’s tours by a historical society, there is a Breakwater that was torn down before its owner was cold in the ground.

The Newport mansions are also a reminder that oligarchy isn’t a distant, quaint memory. As we exited the gardens of Marble House and walked along the Cliff Walk edging the sea coast, we passed four adjacent properties all owned by the seventh richest man in the world, a tech billionaire.

“Not Your Mother’s Romance Novel”

In the romance community, progress is framed as distancing not just from the genre’s history, but from the people, often women, who created and consumed the genre.

“Not your mother’s (insert noun here)” is a well-known phrase used to convey progress for women by stepping on the women who made the future possible.

It is the equivalent of the meaningful glance, an agreement between young women and the patriarchy that our mothers cannot reason as we do.

The rhapsodizing about how each new generation is pushing for change in the romance genre is a denigration of the tastes and trends of the previous generation, without recognizing that while cover styles and subgenre trends may come and go, we are drawn to romance for all the same reasons as our mothers’ generation.

Cultural context evolves, sure, and our media will adapt to mirror our reality. The louder parts may get quieter, but the whispers tell the same stories.

Time marches on and each new generation gets the privilege of coming of age, at which point they get to discover and “improve” and radicalize that which came before.

The sad truth about time and human mortality is that was once young and fresh becomes old and stale. Today’s twenty-something cool girls are tomorrow’s forty-something boring moms who transform into their final form as crazy old cat ladies before being relegated to dust. Whether a woman reproduces or not, she can’t escape the inevitable decline into pitiable figure: the unfuckable hag who serves as media and social foil to the new crop of young women whose choices are worthy of attention until they’re not.

If it seems like I’m cherry picking major media publication headlines, let me assure you that it would be harder to find those that contradict the narrative I’m trying to convey than ones that do.

The narrative goes like so:

“Romance is more popular than ever” (citation needed), “driven by [depending on what year it’s published] Gen Z/Millennials/Gen X/‘the youths,’” and “new romances and their readers aren’t regressive like they used to be: [insert derogative example of embarrassing fantasies of old].”

It’s not a new narrative. I’m as likely to find examples of this from the 1970s and 1980s as I am to find it in an article published this decade. For example, from The New York Times in 1983:

With the boom has come an evolution of the romance novel. Although the form has remained much the same and there are happy endings to each book, the heroine often is now the more powerful half of the relationship.

''In the early romances when the heroine looked at the hero, she shivered and shook but she didn't know why,'' Mrs. Gissony said. ''The books have come to represent a filtered-down feminism. Certainly it's not aggressive, but now women often make the first move. We have a heroine in one of our books who is an astronaut.'' …

According to editors at the conference, the average reader of the romance novel, as well as the writer, is a woman, between 25 and 40 years old, who works outside the home and reads the books for escape.

I could go on, but I’m pressed for time and Substack email length limits, and you get the picture.1

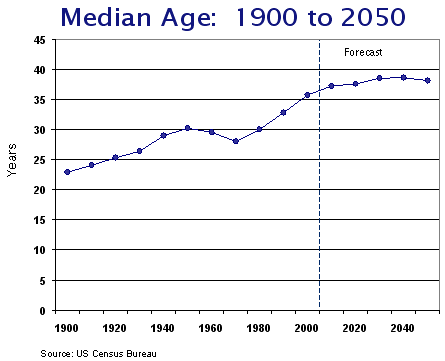

Strangely, it never occurs to anyone writing these trend pieces to consider that the median age in the US has consistently fallen between 25 and 40 years old for the past 100 years, making it far less interesting or notable that the typical romance reader is in fact just the profile of a typical woman.

I’m exactly the median age of a US citizen. I teetered into boring mom a full decade ago and if spotted in a bookstore buying romance when a lifestyle journalist visited, I wouldn’t be selected as a representative of the cool young generation clamoring to romance.

One of the benefits of age is perspective, and I have the added benefit of 25 years of reading romance and an interest in reading romances published before I was born.

I can recognize how the genre has evolved to adapt to its changing environment while also respecting that the bodice rippers of ye olde days, the ones my mother never read but could have, are just as likely to be revolutionary, prosaic, cringeworthy, regressive, and appealing as the ones published today.2

Of course our desire is to make progress — the idea that the romance genre has come a long way, baby3, is a fantasy that has been sold to us because it makes us feel good. It’s the same wishful thinking that convinces us that we’ll never get older and become the very thing we positioned ourselves as superior to: our mothers.

Happy mother’s day.

Further reading

Romance Reader Stereotype:

Actually, romance probably isn’t bigger than it ever was before, but we should understand the appeal of that narrative:

“Romance novels court changing fancies and adorable profits”

“Women’s fantasies have moved from the bedroom to the boardroom,” observes Gallen’s editor in chief, Judith Sullivan.

“They’re no longer dreaming of being kidnaped by pirates, they’re thinking about the guy in the corner office. The core fantasy is wealth, power, clothes, travel and a glamorous career. But women still don’t want to be responsible for their own pleasure.”

You can consume my entire backlist of podcasts and Substacks if you’re looking for citations, you could devote a few years to engaging in our own research, or you could choose to believe me.

Back in the 1960s, cigarette brand Virginia Slims created an iconic advertising campaign that piggybacked on the feminist and Civil Rights movement with the slogan, “You’ve come a long way, baby.” Featuring stylish and aspirational models of modern womanhood, presented “Virginia Slims as the choice for strong, independent, liberated women.”

I misread footnote #1 as 2021 bc it is the broken record that keeps repeating! *sobs

(happy mother's day, Andrea!)

This blew me away from the first quote to your last line. Thank you!