Who Owns Romance Reader Data?

What happened to romance reader surveys? Audience research in the age of the data economy.

Have you ever wondered who holds all the romance reader data? I have been thinking about this a lot, especially in light of BookTok’s potential/impending demise.

Romance publishers used to collect a lot of data from their readers, and this was especially true in the incredibly competitive, disruptive era of the “Romance Wars” in the early 1980s. (More on this later!)

Who owns romance reader data in 2025? That would be Amazon, TikTok, Meta, Google…

You get the picture. All of these companies — whether you think of them as retailers, search engines, or social media platforms — are essentially data companies.

Data is power: it’s the ability to predict, to personalize, and promote. Data is power, and power is control.

Major media and publishing media platforms claim that BookTok is a huge reason why romance is selling more print copies in recent years.1

Huge, if true, because that means that a primary source of data about romance readers is a black box to publishers, and the platform influencing them is one that is singularly focused on keeping people scrolling on the platform instead of buying and reading books.

What happened to romance reader surveys and audience research by publishers?! And, oopsie, was it kind of a mistake for publishers to abdicate control of their reader data?

Know Thy Audience

It’s a bit of a jump scare when I’m operating in the context of “Shelf Love” Andrea and realize it would be helpful to tap into “professional marketer” Andrea. It turns out that the LinkedIn page version of me has a lot to say about data, audience research, and romance publishing.2

The key to a good strategy period is knowing your audience. Marketing is not about selling things to anyone who will buy it — it’s about connecting a product with the people who find value in your product.

The best products come from insights about not just who the product is for and what they say they want, but understanding what benefits your target audience is seeking.

Romance Publishers’ War on Data

Data about romance readers is a valuable competitive advantage. This was never more clear to romance publishers than in the early 1980s.

For most of the 1970s, Harlequin (the dominant publisher of romance novels in North America at the time) worked with Simon & Schuster to handle distribution in America. In 1978, Harlequin notified S&S that they would handle it themselves going forward. Simon & Schuster wasn’t happy to lose their piece of the romance supply chain pie, and responded by launching Silhouette romance in 1980 to give Harlequin some competition for once.

Thus began “The Romance Wars,” a term coined by Vivien Lee Jennings in a 1984 Publishers Weekly article.

What’s notable about this period is that it was a period of huge capital investment to gain market share, which also resulted in growing the overall market. There was an explosion of new romance publishing imprints, category lines, and growth in retail store space and in the public consciousness.3

[If your ears are perking up because this sounds like how the current romance renaissance is playing out, with the “newfound acceptance for romance” and an explosion of romance bookstores, you get an A.]

Harlequin and Silhouette were at each others’ throats, throwing millions of dollars at advertising in an attempt to claim more market share, but pretty much every paperback publisher threw their hat in the ring, too.

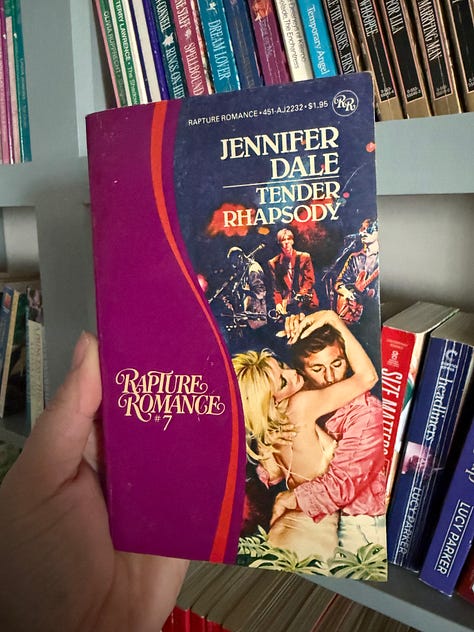

Each new category line and imprint needed to stake out a distinct position in the market along lines of subgenre, level of on-page sensuality, hero and heroine archetypes, and cover style.

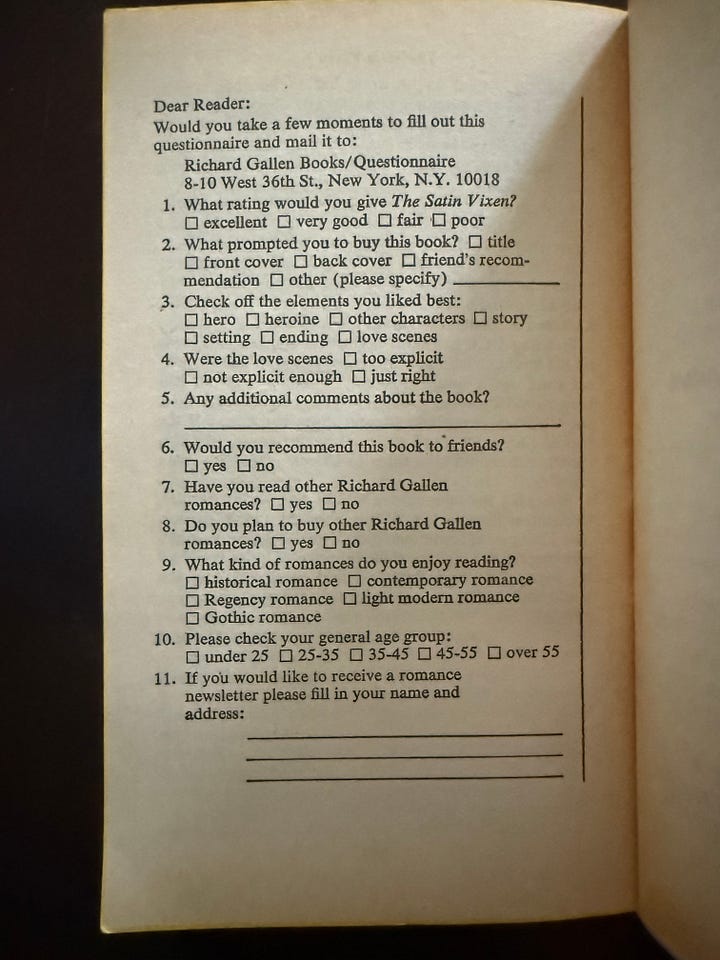

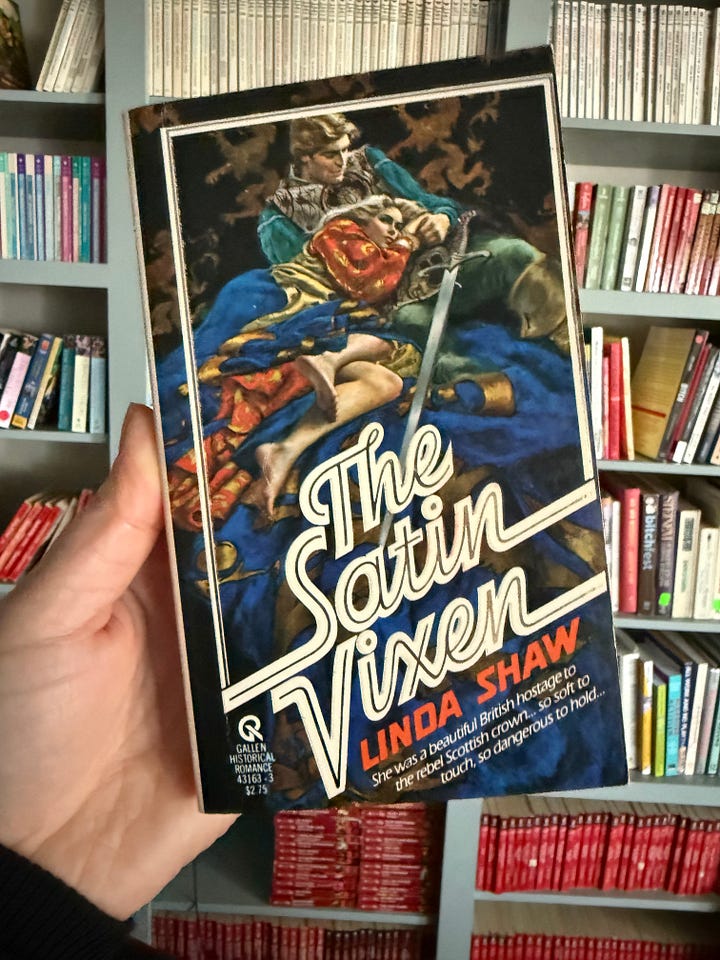

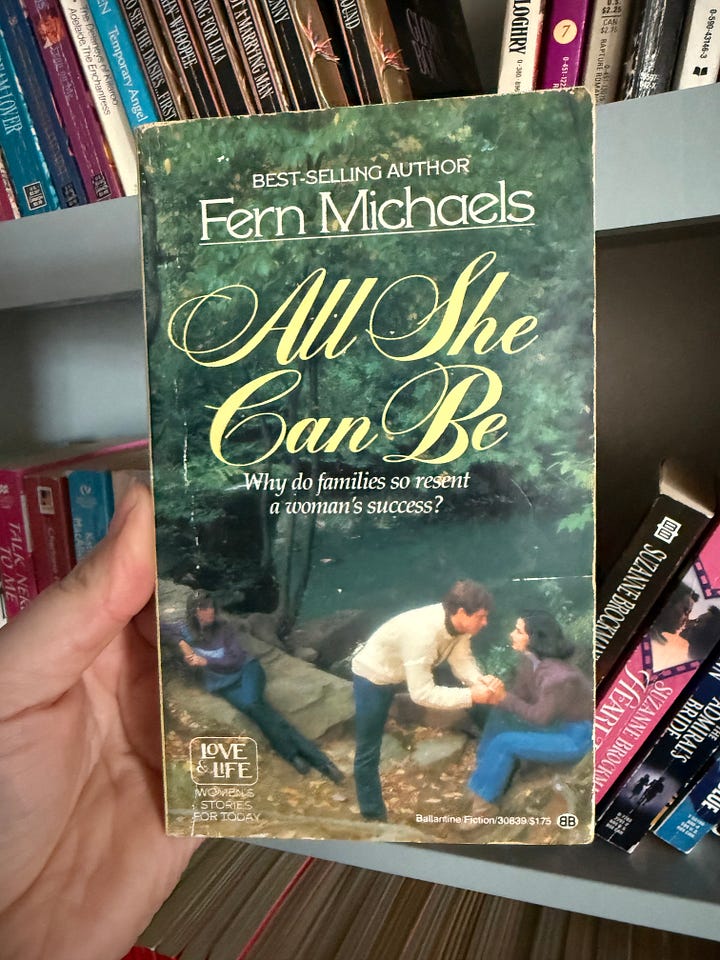

This was a bit of educated sociological guesswork on the part of editors (for example, Vivian Stephens did her own informal study of romance buyers before pitching the sexy-for-its-time Dell Candlelight Ecstasy), but most lines tested their hypothesis with focus groups prior to publication (especially Harlequin and Silhouette) and reader surveys after publication, found in the pages of the books themselves. These surveys would provide invaluable information about who was reading their books, how they bought them, and what they liked or disliked about the book, category line, or elements of the story.

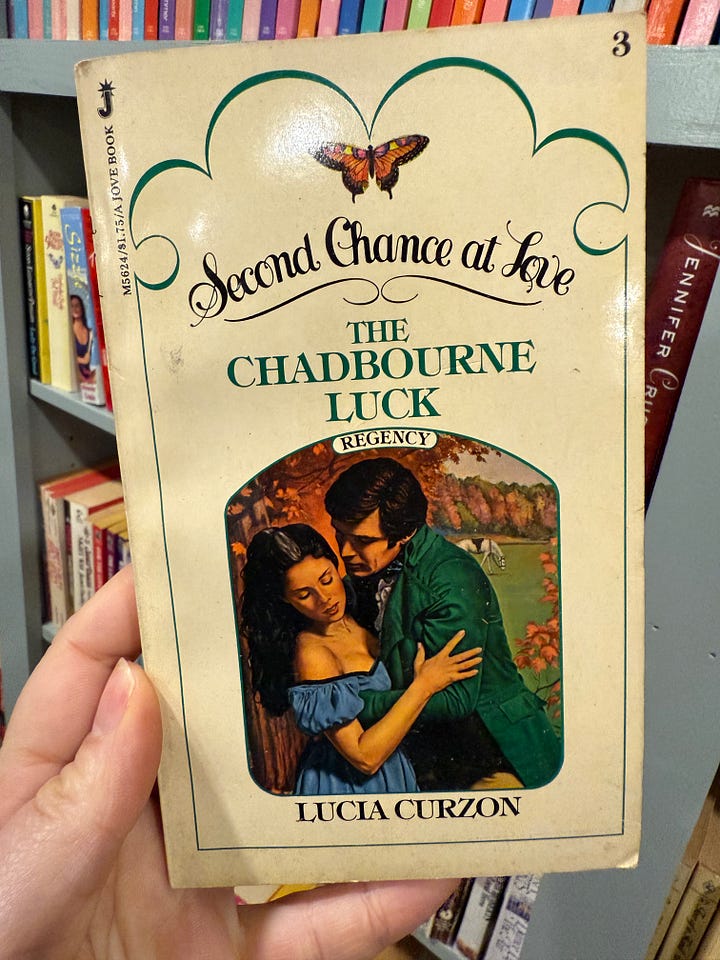

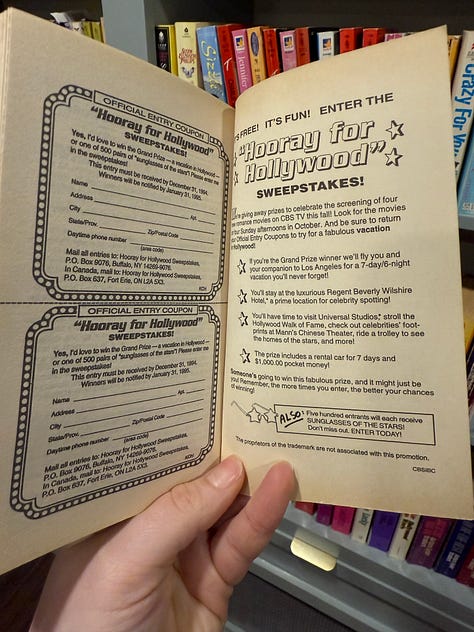

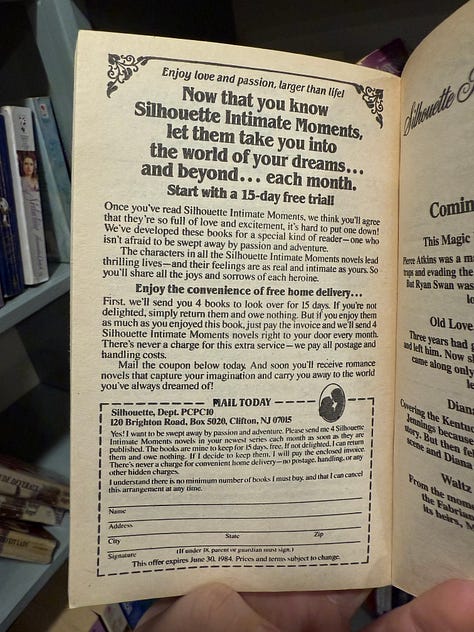

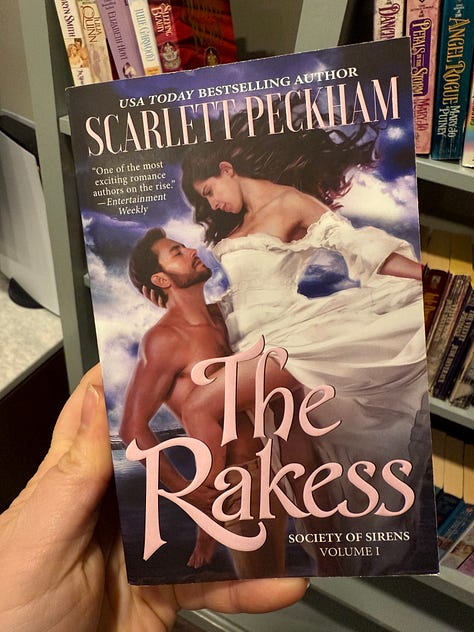

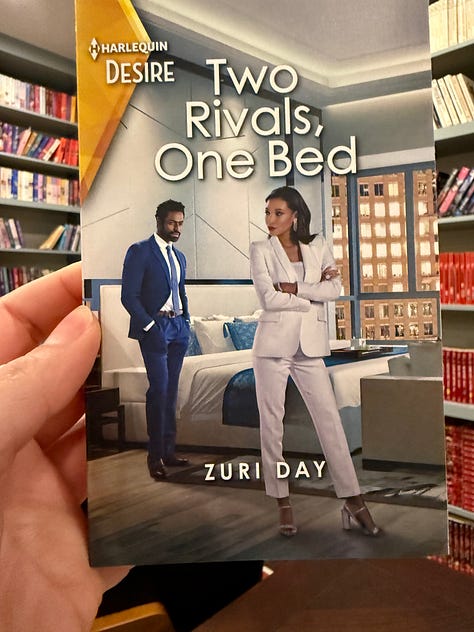

I have 1,737 romance novels4, so I grabbed a few examples:

(Ironically, all of the surveys above are for unsuccessful or short-lived lines — data doesn’t guarantee success.)

Other tools to gather and maintain/control romance reader audience data included mail-order subscription lists, which also cut out a third-party retailer and guaranteed repeat sales, as well as romance reader newsletters and mailing lists. All of those sweepstakes offers in old paperbacks were a way to collect data about their audience so they could market more effectively to them.

I don’t have any insider information on this, but as a Professional Marketer™ I would speculate that these lists of readers and their data were leveraged for additional marketing or reader research.

For example, direct mail offers could be sent to readers’ addresses once collected for a no-obligation sweepstakes, or they could understand metros where readers were concentrated and could strategically plan author tours or bookstore signings.

Codes embedded in the response cards would likely be tied to specific books, thus enabling publishers to get some understanding of which titles were successfully converting new loyal readers, or which books and authors appealed to specific readers.

Publishers Give Up on Reader Data?

It kind of seems like, somewhere along the way, publishers gave up on collecting romance reader data.5

From my perspective, it seems like publishers are looking at social media stats to “understand” the market, as if a trending hashtag equals a meaningful insight. There doesn’t seem to be any sense of audience segmentation and targeting different books to different audiences. It seems like publishers gave up on building useful email marketing lists and instead push readers to follow them or authors on social media.

Romance publishers are not using the physical real estate they control to attempt to gather data on romance readers. I don’t have any data on this, but I would imagine that Harlequin’s mail-order subscriber circulation has reduced dramatically, especially among younger readers, leading to even more reliance on third-party retail sites (physical and digital) that control sales and reader data.

Even if publishers encourage social media connections, we all know by now that individuals and companies do not “own” that data, right? The platforms can limit access to people who opt in, charge you to even show them your content, dictate terms of service, and can choose to close your account down completely if they want to.

Data is Power: Data is Control

Let’s come back to those tech giants that control all of our data generally, but pertinent to the content of this newsletter, also control the data about romance readers and the romance market.

What are their incentives? How do they make money and create value?

On any social media platform, you are the product. Your attention is what is being sold to advertisers. Why did Amazon acquire Goodreads? Not to make the platform better! It was to get your data.

TikTok doesn’t sell books: TikTok sells access to you…in other words, your data. You’re data.

TikTok wants you to spend as much time on the platform as possible, endlessly scrolling book content where you’re building your TBR and liking pictures of color-coordinated shelves and book stacks, and maybe also engaging with interesting or rage-bait discourse. Some of this is fun, or relaxing, or helping create a feeling of community.

TikTok does NOT want you to leave TikTok to read a book. Maybe you succeed in doing so, but that is not TikTok’s goal. The only way they will use romance reader data is to keep you on TikTok.6 They certainly won’t be sharing anything with publishers to help them understand what’s really resonating with readers so they can acquire the right books and connect them with the right readers.

And so now, publishers are standing on the outside, just like us, trying to read the tea leaves of trends based on the noise, but potentially missing the signal.

Publishers still have data on number of copies sold, of course, but there’s a big difference between buying a book and reading it or enjoying it. Amazon knows how much of an eBook we read before giving up, but publishers don’t.

Purely my opinion here, but I think that traditional publishing’s output also shows that they don’t know what readers want anymore, and are perhaps confused about who their target audience is and where to focus their energy.

…but I don’t have the data on that, so who could say?

Misc. and Sundry

I’ve been toiling away on a beast of a post for the better part of 2 months. (Not this one.) If I’m honest with myself, the ambition of that post is more aligned with a book than a Substack post, so I decided to put it aside for today and tackle something more bite-sized. (Well…I tried anyway.)

I finished my built in bookshelves and catalogued my entire romance and romance scholarship collection!

As I was writing this, this post from Kyla (“human-centric economic analysis”) came through about the evolution of value creation. It’s interesting in the context of the post you just read…

It pains me to write this — if you’ve been here for a while you know that I have a lot of thoughts about romance market data. It is actually credible that print sales of romance have gone up in recent years, however that does not necessarily translate to the entire genre sales in all formats, and the growth is only compared with 1-2 years of previous sales, not a longer time scale.

My point is: do not extrapolate from this statement that 1. there’s actually any causal relationship between TikTok and romance sales (it is an observed correlation), and 2. that one decontextualized data point proves that romance is more popular than ever.

For more on this:

For context: I have a master’s degree in Integrated Marketing Communication, taught marketing at the college level, and have worked in marketing for over 10 years after transitioning from my early career in magazine publishing. My specialty is content strategy and data analysis. I know this may be a huge surprise given the footnote above.

This period of investment and growth was followed by a cooldown period when the oversaturation led to audience fatigue. Readers felt that quality was diminishing — turns out printing more romance wasn’t the same as printing money. Harlequin bought out Silhouette, thus ending the fighting between mommy and daddy, many lines died out, and the market entered a new phase of stability and maturity.

This is an accurate count. I recently catalogued my entire collection. I really like data!!

There has been a massive amount of disruption to publishing in the digital age. It would take a book and more insider knowledge than I have to examine the ways publishers lost ground either through their own myopia or through forces beyond their control.

And also to influence what you see and don’t see! I really don’t have time to get into algorithms and how easily they can be manipulated to control access to information and shape narratives…

Data and marketing and sales and I are not super well acquainted, so this question may not be completely consistent with the piece, but I’m curious to understand the impact on readers. If publishing companies don’t have direct access to the data, could it be said that we are essentially having broken conversation wherein the publishers aren’t meeting reader expectations/wants and readers aren’t able to fully communicate that want? In terms of practical impact, what are we seeing readers experience? (Also, if this question is way off base or if I missed the answer within the piece - I apologize!).

As a data analyst and a romantasy writer, I am appalled the publishers have abdicated control over their own data.