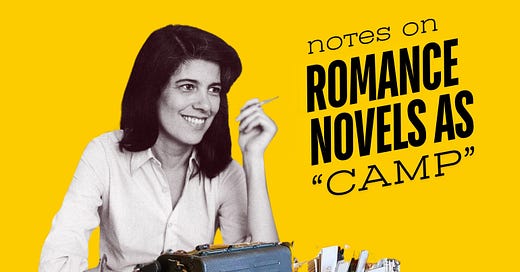

Today, I will passionately, unseriously, extravagantly, and, with a degree of style, explain how I think romance novels function as the sensibility known as Camp, referencing and riffing on Susan Sontag’s iconic 1964 jottings, “Notes on ‘Camp.’”

I will emulate Sontag’s style of notes, because I too would be embarrassed to be solemn and treatise-like on this topic.1

1. Camp is a sensibility embedded in a private code

“It is not a natural mode of sensibility, if there be any such. Indeed the essence of Camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration. And Camp is esoteric — something of a private code, a badge of identity even, among small urban cliques.”

The internet and its ability to enable communities to form and scale without regard for location has negated the requirement 60 years ago for the private code to be limited to a “small” or “urban” clique.

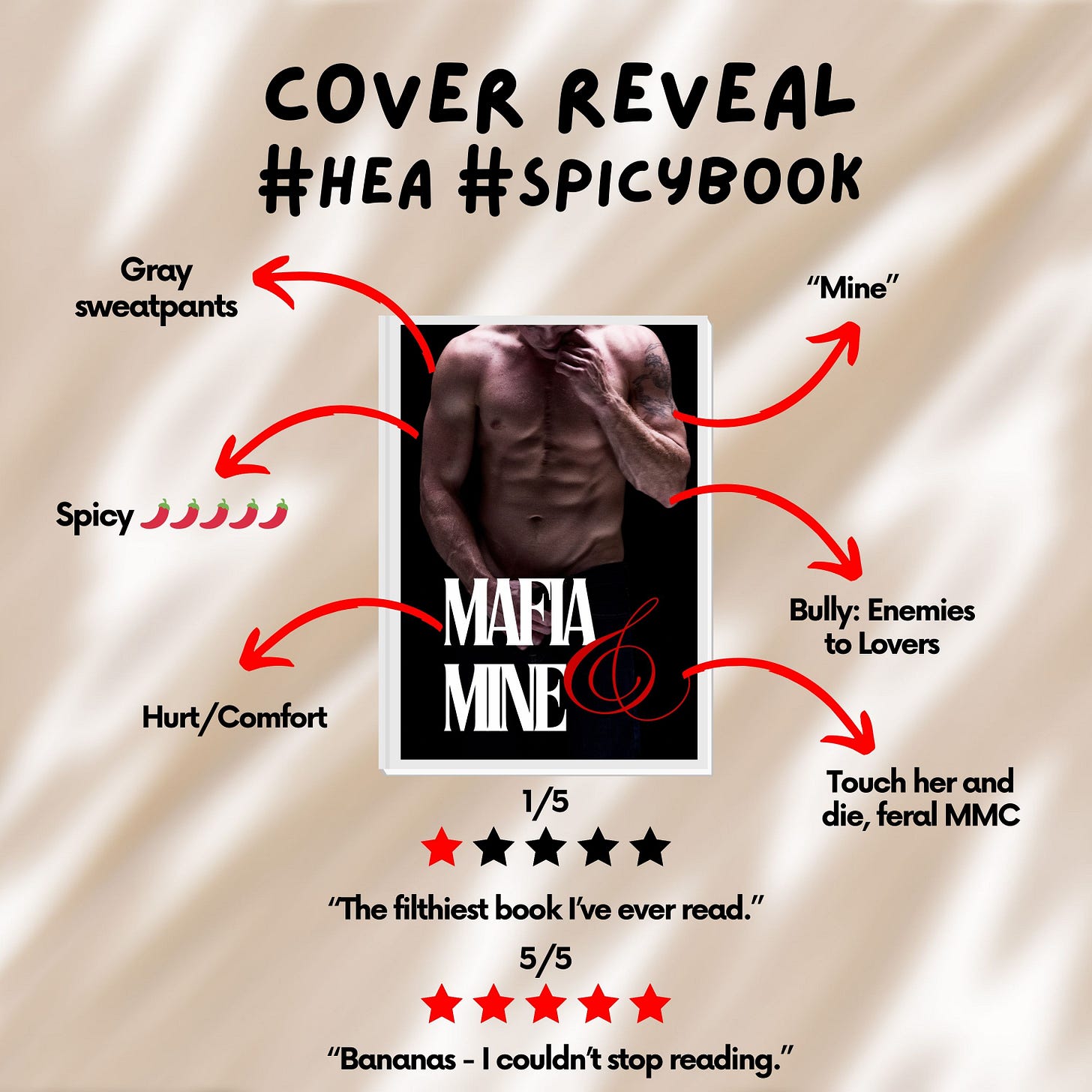

Aside from this, Sontag’s description of Camp as a sensibility for artifice and exaggeration, used as a private code that becomes an identity is an accurate way to describe the extravagant tropes, visual signifiers, and archetypes found in the romance genre and understood and appreciated by the romance-reading community.

The current style of book promotion on social media is a pointed illustration of this.

Not all romance novels or aspects of the genre are Camp, and not all members of the reading community look at the genre through the lens of Camp.

But perhaps, another way of saying this is that the defining characteristic of romance novels (to me) is that they share a sensibility and not (just) a structure. I think that sensibility is Camp. When romance novels are absent of Camp, they do not feel like romance novels to me.

Sontag describes the sensibility of Camp as being akin to “taste,” and that taste is different from subjective preference.

The art of recognizing a successful romance novel depends on understanding the sensibility of a romance novel. This requires an insider familiarity and explains why most major media platforms cannot be trusted to create a list of great romance novels without adding The Great Gatsby or The Notebook.

2. Camp dethrones seriousness

“The whole point of Camp is to dethrone the serious [and create] a new, more complex relation to ‘the serious.’ One can be serious about the frivolous, frivolous about the serious.”

Recognizing a successful romance vis a vis its Camp sensibility is not to be confused with the criteria distinguishing successful literature or subjective preferences in romance novels. When romance seeks to be taken seriously by those that lack the sensibility for romance novels, they fail as romance novels and they fail as Camp.

Normal People by Sally Rooney does not purport to be a romance novel, and yet people who lack the sensibility for romance novels believe it to be an example of a serious romance novel, which is to say, a literary romance novel.

“But there are other creative sensibilities besides the seriousness of high culture…and one cheats oneself, as a human being, if one has respect only for the style of high culture, whatever else one may do or feel on the sly.”

The sensibility of romance is Camp because it respects the seriousness of fun and affect. By existing — on store shelves, as something we do instead of something “more productive,” by being doggedly popular — it calls into question the “natural” order of value.

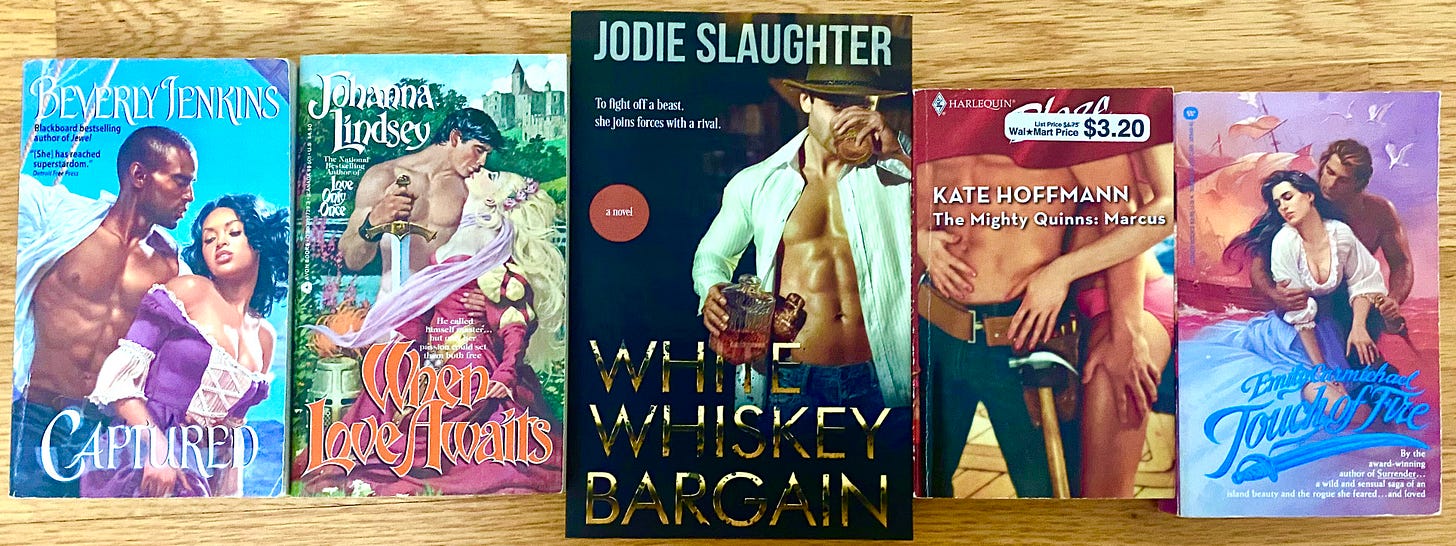

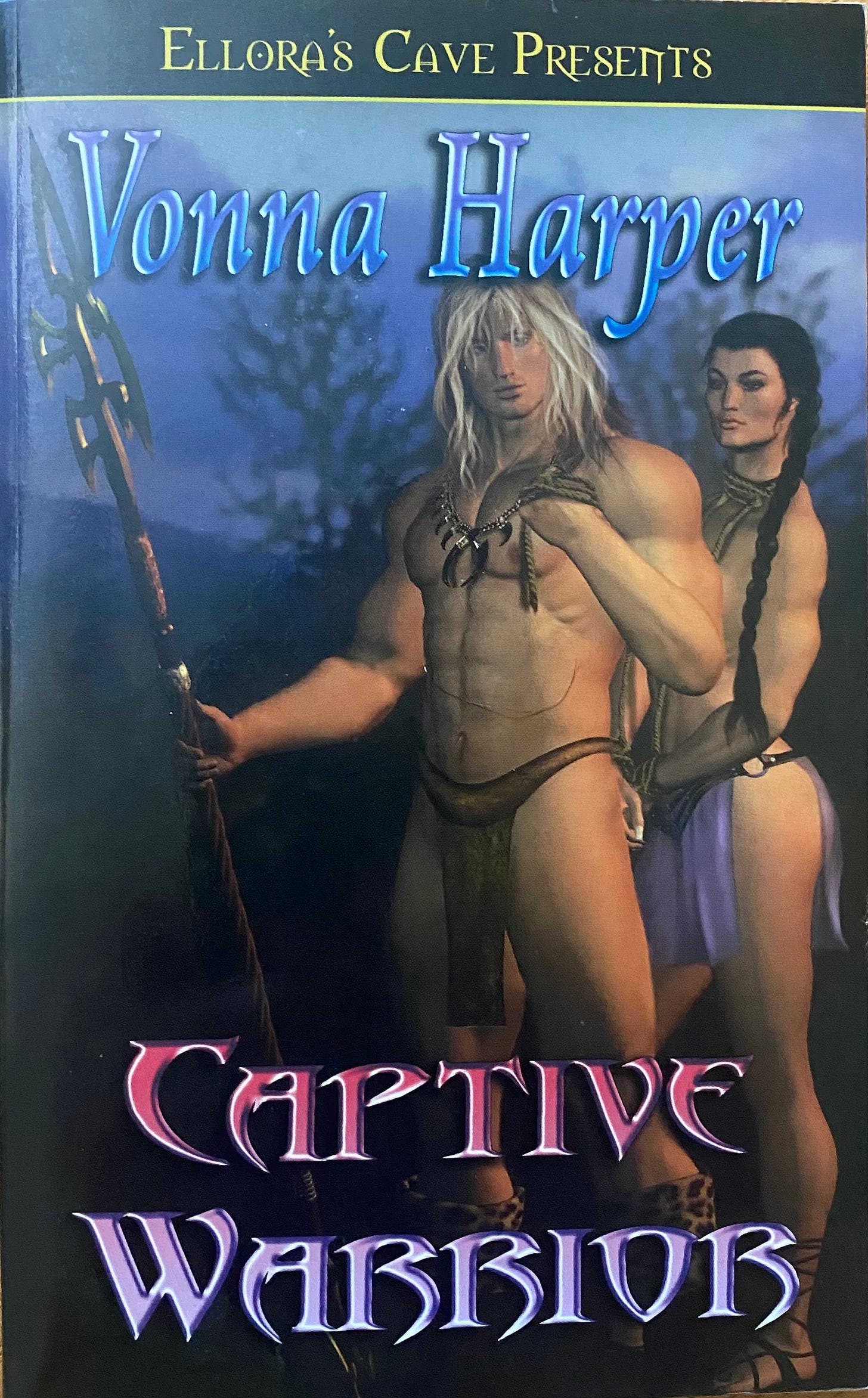

3. Random examples that are part of the canon of romance Camp:

Romance novel covers that blatantly advertise that they’re romance novels

Hot, young, single billionaires/aristocrats who are all friends

Ruggedly masculine faces with noses that appear to have been broken more than once

Barbara Cartland

Tropes: fated mates, there’s only one bed, enemies to lovers

Women that smell sweet, men that smell like horses and leather

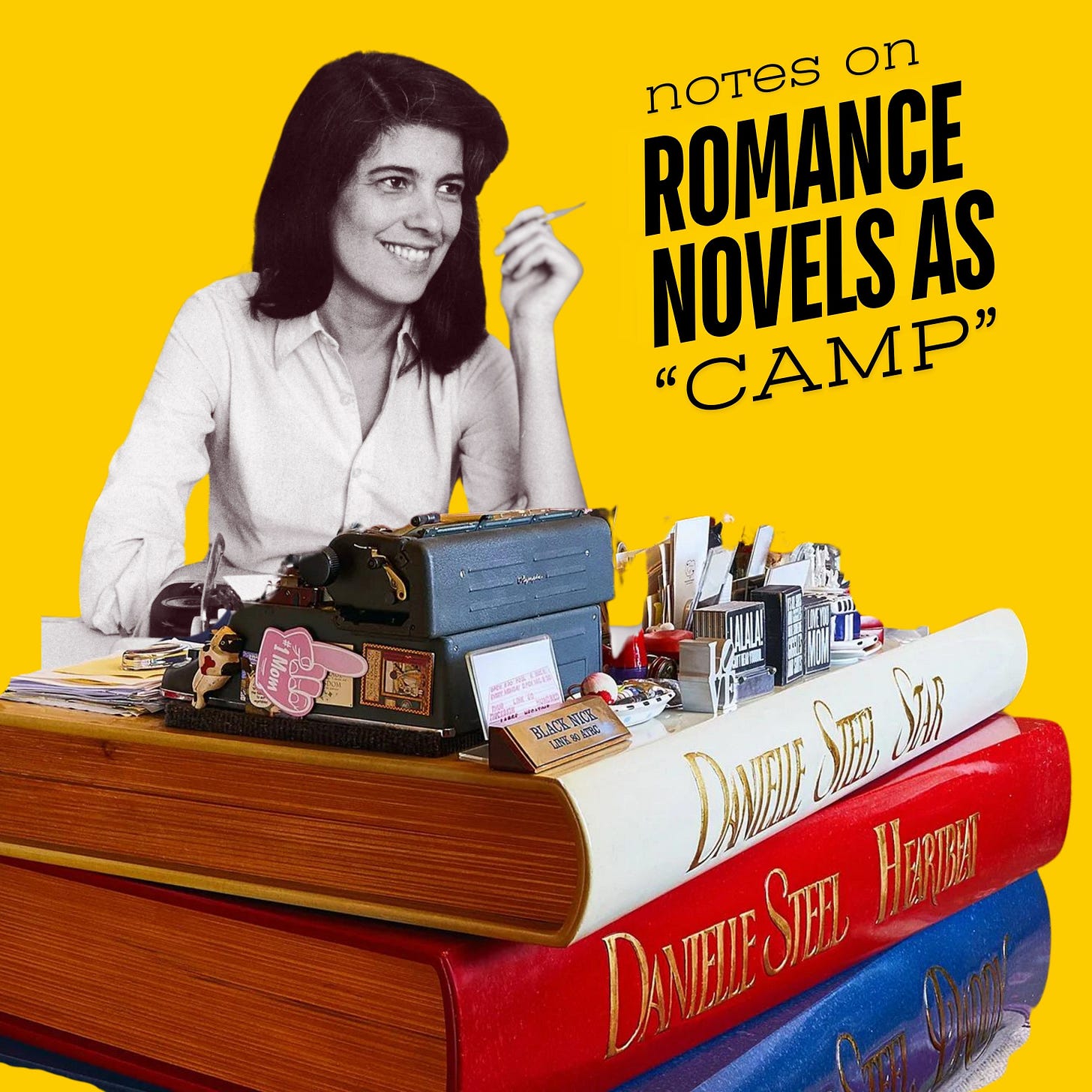

Danielle Steel’s desk

Fabio

Jessica shooting Dain in Lord of Scoundrels by Loretta Chase

Ellora’s Cave

4. Escapist fantasies are Camp

“Sometimes whole art forms become saturated with Camp,” Sontag notes, especially in cases when they are consumed in a high-spirited and unpretentious way.

While the public perception of romance novels and their readers is categorized as a paternalistic stereotype and results in pity, the private consumption of romance does tend to be high-spirited and unpretentious, as long as the reader is able to restrain any of their own internalized prejudice.

The solitary and private experience of reading a romance novel makes the genre a fertile ecosystem for Camp. They are acknowledged as “escapist fantasies,” and so their frivolity becomes their greatest defense for pleasure.

5. Romance evades reality

All fiction is artifice, but romance novels, when they are not trying to be something else, exaggerate and evade reality.

“All Camp objects, and persons, contain a large element of artifice…It is the love of the exaggerated. Camp sees everything in quotation marks. It’s not a lamp, but a ‘lamp’; not a woman, but a ‘woman.’”

In romance, every man is a “man”; the Regency period is “Regency,” the happily ever after becomes the “HEA.”

Sontag describes Camp as “the triumph of the epicene style… Life is not stylish. Neither is nature.”

Romance avoids matters of both nature and life: by riding off into the sunset, relationships forged throughout the course of a novel (and central characters) never die. Six packs come into being off page, someone else empties the chamber pot, and nobody has morning breath.

“Today’s Camp taste effaces nature, or else contradicts it outright. And the relation of Camp taste to the past is extremely sentimental.”

Romance loves colonizing the past as a way to escape the present, but remake it to satisfy the fantasies of the present with little care for the issues of the past.

6. Camp in romance plays with gender

Sontag writes that the Camp sensibility has a taste for the androgynous.

To paraphrase and expand, in romance novels what is most beautiful in virile men is the ability to be tender and emotionally competent (considered feminine traits), and what is most beautiful in feminine women is agency and intelligence (considered masculine traits).

At the same time, Sontag describes:

“a relish for the exaggeration of sexual characteristics and personality mannerisms.”

“Men” in romance novels are alpha males that stand out as the tallest, the broadest, the strongest, the most competent. Their only peers are the cohort of other romance heroes that inhabit the world. “Women” may not objectively be the “most” feminine via sexual characteristics, but to their love interest, they embody all that is desirable about “woman.”

Is it gender essentialism, is or is it playing with gender the way drag performers call attention to the performance of gender via exaggeration?

The exaggerated heteronormativity embedded in the sensibility of romance is one area that disturbs me, even as I understand the historical and cultural context that explains it and eroticizes it.

7. Romance can be both artificial and meaningful

Sontag describes the Camp sensibility as “alive to a double sense in which some things can be taken” and explains that this isn’t just the dichotomy of literal vs. symbolic meaning.

“It is the difference, rather, between the thing as meaning something, anything, and the thing as pure artifice.”

Romance readers who understand the Camp sensibility understand that the books are not real but they’re also not not real. They’re about relationships that don’t exist and that we don’t want to be part of while also articulating our desires. Even when we see the artifice of only one bed, we can still feel the frisson of excitement.

8. Romance fails when it’s too mediocre in its ambition

“Camp is art that proposes itself seriously but cannot be taken altogether seriously because it is ‘too much.’ … When something is just bad (rather than Camp), it’s often because it is too mediocre in its ambition.”

Romance celebrates excess: emotion, passion, character, plot.

Dark romance, one of the campiest sub-genres within romance, is populated by mafia dons, bikers, serial killers, and psychopaths. It is often too much, but when it fails (as a romance and as Camp) is when the violence is banal, or worse yet, hinted at but not shown. It purports to be too much but isn’t even enough.

Without passion, one gets pseudo-Camp—what is merely decorative, safe, in a word, chic.

In the age of social media, romance authors are increasingly choosing to write safe stories that seek to not offend rather than swinging for the fences. The books lack passion, not just in terms of sexuality but in terms of life.

The worst part is the false advertising. More than once, I’ve seen a book promoted as a sexy enemies to lovers and the author refuses to actually let the characters be enemies for a page. They don’t trust themselves or the readers enough to go too far.

9. Types of Camp

Sontag makes a distinction between pure “naive,” unintentional Camp and deliberate, or self-aware Camp.

“In naive, or pure, Camp, the essential element is seriousness, a seriousness that fails. Successful Camp…even when it reveals self-parody, reeks of self-love.”

You’re either all in or you’re all out — Fly…Or Die.

Fourth Wing by Rebecca Yarros is naive Camp. It’s dead serious about lacking seriousness, and it fails — but it doesn’t lack for ambition. It fails so extravagantly that it succeeds.

Iron Flame by Rebecca Yarros is trying too hard to be serious and fails, but it also lost its ambition to be fun. Yarros expended all of her extravagance in her opening salvo and there isn’t enough passion to keep the momentum.

Bet Me (and perhaps the majority of the titles) by Jennifer Crusie are self-aware Camp. The slapstick, the references, the extravagance — it’s all intentional, but it’s always loving. The cynicism in the text is for the world, not the genre.

Joan Wilder, the romance novelist in Romancing the Stone, is writing naive Camp.

Loretta Sage, the romance novelist in The Lost City, is failing at Camp…

however the movie itself succeeds as self-aware Camp.

10. The liberation of having good taste of bad taste

“…high culture has no monopoly upon refinement. Camp asserts that good taste is not simply good taste'‘ that there exists, indeed, a good taste of bad taste… [and this] can be very liberating.

Camp taste is, above all, a mode of enjoyment, of appreciations — not judgement. Camp is generous. It wants to enjoy.”

Yes, romance is ridiculous, extravagant, passionate, “too much,” unnatural, lacking seriousness.

The art of loving romance isn’t hard to master, but it does require letting go of the idea of high culture as the only cultural capital that matters.

Romance novels are Camp because how else can books that are universally agreed to be awful be so enjoyable and so loved?

If you can’t tell, I recently read Fourth Wing and you can hear a discussion about it on the podcast soon.

Recent Shelf Love episodes (you know this is a podcast, right?) are about The Hating Game (teaching the book and adaptation) with Dr. Diana Filar, Cold Hearted by Heather Guerre with Dame Jodie Slaughter (as in, slaughterhouse, and Cannibalism (but really more about consuming desire and why we want to bite chubby baby legs) with Dr. Nicola Welsh-Burke.

No, seriously though. I would love if you participated in a bit of market research. This will help me create better content. It’s hard to tell how much overlap there is between audiences…

“To snare a sensibility in words, especially one that is alive and powerful, one must be tentative and nimble. The form of jottings, rather than an essay (with its claim to a linear, consecutive argument), seems more appropriate for getting down something of this particular fugitive sensibility. It’s embarrassing to be solemn and treatise-like about Camp. One runs the risk of having, oneself, produced a very inferior piece of Camp.”

Susan Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp’” 1964 (page 2).

Naive camp is The Most Perfect description of the super popular stuff I’ve attempted to love but can’t and probably why I am a huge J. Cruisie fan. Thanks for this!

This absolutely SANG to me: “While the public perception of romance novels and their readers is categorized as a paternalistic stereotype and results in pity, the private consumption of romance does tend to be high-spirited and unpretentious, as long as the reader is able to restrain any of their own internalized prejudice.”