Colonizing History: Historical Romance

The inconvenient truths that conflict with romantic fantasy worlds

Popular romance fiction has colonized the colonizer: Regency England. At the same time, the romance readers’ romantic imagination of history has been colonized by the Regency.

New readers of romance who are asked to describe “historical romance” may automatically find themselves thinking of Bridgerton, Pride & Prejudice, and the plethora of books dominating store shelves with covers featuring ladies in empire-waist gowns with cap sleeves falling provocatively off a creamy shoulder.

In other words: Regency romance set in England, which is but one slice of 9 years out of the vastness of time, in one country out of hundreds.

But historical romance hasn’t always been dominated by books set in the Regency.

Why did the audience gravitate to the Regency specifically? Is it less about what the Regency setting offers, lush and plushly confected as it is, and more about what can be erased from visibility without readers’ detection?

In this post, I’ll explore two related observations:

The first is that by reading older historical romances that are often called “problematic,” readers witness historical events and contexts that they may find uncomfortable, especially when the characters they’re put in the position of inhabiting don’t behave in an unambiguously “heroic” way.

The second is that Regency England as presented in romance, via collective and evolving world-building across romance texts, is a colonial project that displaces the original inconvenient histories by occupying the space with sanitized fantasies that can be exploited for modern audiences’ comfort.

A brief history of the Regency romance

The popularity of the Regency period in romance is usually credited to two influential authors, and I’ll throw in a third who should be included due to the sheer number of Regency and Regency-adjacent work she put out into the world:

Jane Austen (1775-1817)

Austen lived through and set her books in the Regency period (1811-1820), so at the time she was writing contemporary romance.

Austen is often credited as writing the proto-popular romance novels that contemporary authors use as a model and inspiration.

Georgette Heyer (1902-1974)

Heyer’s writing career began in 1921, but she wrote her first Regency, the aptly titled Regency Buck, in 1935, and was inspired by Austen’s contemporary novels of the period.

Heyer prided herself in her Regency research, and in her time also accused other authors (cough Barbara Cartland cough) of using her books as the source of their own “research.”

Many Regency romances from our century explicitly draw on Heyer’s research and world-building, which is NOT GREAT given how Heyer infused her work with the cultural and personal baggage of her own time, including anti-semitism.

Barbara Cartland (1901-2000)

A contemporary of Heyer who was much more prolific (there are claims of 723 books written in her lifetime) and much less fussy about research (cough maybe “borrowing” from Heyer cough).

As Cartland was a notorious fame monger (in contrast to Heyer’s reputation as a recluse who shunned the spotlight), and she also lived a quarter century longer than Heyer, Cartland’s influence looms large in romance. She had lots of opinions about what romance novels should and should not include, and was famously pro-virgin and anti-sex in romance.1

50 years of historical romance

Regencies are historical romances, but prior to the last 25 years or so, they were generally classified as a distinct sub-genre that was not conflated with “historical romance.”

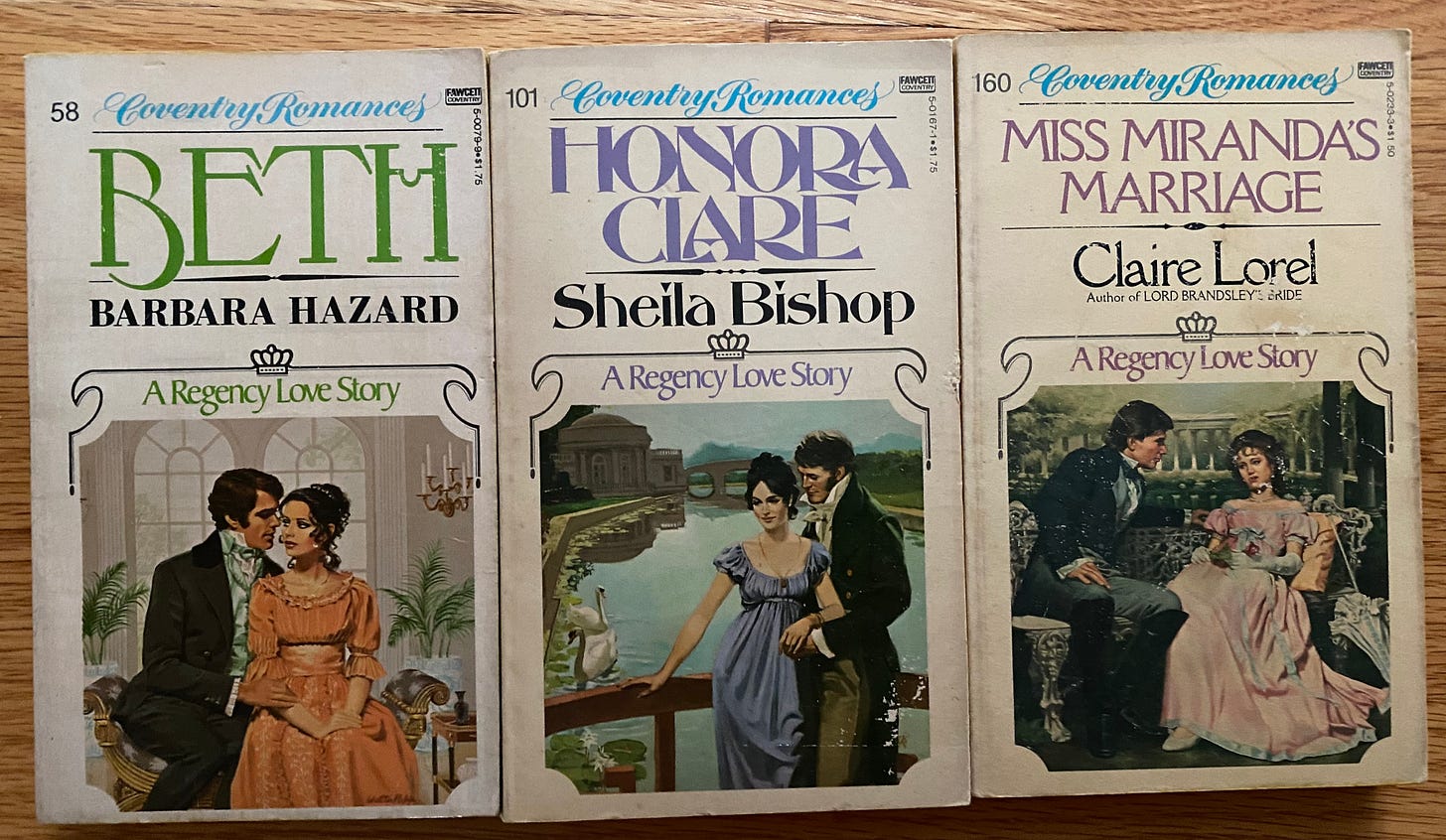

The 1970s were a boom for erotic historical romance that solidified the formula that a happily ever after was a prerequisite in a sexy tale (along with monogamy).2 Regencies as a defined sub-genre had been around since at least the 1930s, but there had been booms and busts — by the 1970s, the genre was considered to be and was packaged as a formulaic commodity.

In the 1980s, there was a surge of contemporary category romances during the Romance Wars.3 To give a sense of where things stood for the Regency in the 1980s, let’s go to a contemporary source.

In Kathryn Falk’s 1983 first edition of How to Write a Romance and Get it Published, Falk spends several chapters explaining the intricacies of “Category Romances” (which were primarily or exclusively contemporary romances), and then a full chapter on “Historical Romances,” but spares just one section of a chapter about “The Other Romance Genres” to discuss Regencies.

Falk cites Heyer and Austen, as well as Barbara Cartland, as prime examples of Regency authors, and notes that the books tended to be short, in contrast with the tomes of erotic historicals that were popular in the 1970s.

Periods & places in historical romance: the way it used to be

When I peruse my shelves of historical romance, especially single title paperbacks from the 1970s through 1990s, I find a wide array of historical periods and places represented — although, just as today (explicitly not saying more so), the majority of “places” were predominantly populated with white people or privileged the experiences of the white characters in a predominantly non-white space.

For example, let’s look at some popular and influential single-title romance authors publishing in the 1970s through 1990s:4

Roberta Gellis was known for her meticulously-researched medieval romances.

Kathleen Woodiwiss tromped through settings from the antebellum South in the United States to 1066 England.

Bertrice Small wrote about the Ottoman empire and her characters traveled between Turkey and Scotland in the 15th century, among other settings.

Johanna Lindsey refused to settle in any particular locale and time (to say nothing of the time traveling within books), and wrote 19th century American Westerns, Viking romance, as well as 19th century British historicals.

And yes, she wrote some books that took place in the Regency, but it certainly wasn’t her sole or majority focus.

This breadth of time periods and places was also seen in historical category romance series:

Sunfire, a series of historical romances for teens in the mid-1980s , focused on American settings, but still brought teen lovers together in a variety of time periods, including the 1600s and the Salem Witch Trials, 1912 on the Titanic, New York City in 1888, and 1867 Alaska.

I could go on, but even anecdotally, you can see great breadth of settings and time periods.

Regency invasion

So, let’s assume that my sense is correct that historical romance in the 1970s and 1980s, into the 1990s, was more diverse in terms of time periods and places represented. Where do we find ourselves today?

The current crop of historical romances feels like 75% or more are set in Regency England.

Feelings, or perceptions if you prefer, aren’t always reliable, so I did a brief quantitative study where I went through the first 3 pages of digital review copies for romance on Edelweiss (in other words, the newest-available books).

I looked at every historical romance (27 total) and found:

63% were Regency (17/27)

30% were Victorian (8/27)

<4% - 1 was Gilded Age

<4% - 1 was from the 1600s

All were set in England.

Duke this, Earl that, Baron the other. There’s a preoccupation with the most privileged echelons of class and wealth (although increasingly we’re assured that these .1%-ers are not just the idle rich, they’re ALSO successful capitalists — but that’s a topic for another day).

A survey in 2018 by Jennifer Hallock found that over 90% of romance readers called Regency one of their favorite historical periods, with just under 28% enjoying Medieval Europe and 5% enjoying the Cold War.5

Hallock’s research explores both reader preference for the Regency and its commercial popularity, as well as the ahistorical elements of most contemporary, 20th century Regencies and how they specifically serve to bolster and explain the popularity.

In this context, she is using “chronotope” as a way to talk about how the tropes in Regency romance come to represent the actual Regency period for readers.6

The chronotope is selectively inaccurate when realism endangers the happily-ever-after. Can you have a happily-ever-after with a slaveowner?… The popular chronotope of 19th century Britain avoids such issues by erasing these uncomfortable aspects of history from the story.

Jennifer Hallock, History Ever After, Part I: The Fabricated Chronotopes (2018)

I’ll come back to the discussion of the specific ways in which the Regency period is made more palatable than it actually was later, but first: what happened? Why did Regencies set in England edge out most other time periods and settings?

Our problematic past

Look, I’m not a history buff. For example, most of what I know about the Revolutionary War comes from popular culture (Time Enough for Drums, Hamilton, and 1776) and middle- and high-school history textbooks.

I’m guessing I’m not an outlier here, in learning about history primarily from fiction, movies, TV shows, and now, increasingly, edutainment podcasts.

I feel historians shuddering here, when I say I “learn” history from these sources. At the very least I’m learning about things in history, meaning I’m hearing about events and time periods’ existence to which I would otherwise be completely oblivious.

One thing I do know is that the past is littered with violence and suffering. You know, unlike today, where we all live in harmony and peace and never hurt our fellow humans… wait a second.

“History” is often framed as a linear progression towards a better future, in which we currently reside. Maybe the world isn’t perfect, but we’re obviously getting better. Right?

The atrocities of the past were produced by people utterly foreign to us, and through the safe distance of time, we are able to sit safe in the knowledge that we would never do such things. We are fundamentally different, having learned from the bad, bad things our ancestors did (even better if it was someone else’s ancestors, adding another layer of blamelessness).

But do we have any right to claim the moral high ground? Or are we just sitting in a very comfortable position where we aren’t confronted with truly difficult choices, or can convince ourselves that we aren’t making choices?

I found myself asking these uncomfortable questions recently as I re-read a romance I first read as a teen, over two decades ago: Fierce Eden by Jennifer Blake, originally published in 1985.

The villain/hero binary

Fierce Eden begins in 1729 in the area currently known as Louisiana, USA. It centers on the events and the aftermath of the Natchez Revolt at Fort Rosalie on November 28, 1729.

The Natchez killed the majority of the inhabitants of the fort, approximately 230 people, and the book doesn’t shy away from exploring, as the story unfolds, the motivations that contextualize the violence against the settler colonial French by the displaced and oppressed indigenous people, the Natchez.

Our protagonist is Elise Laffont, a beautiful 25-year-old French widow who at the beginning of the story is the enslaver of three Black people who are forced to work her small subsistence farm.

The book follows her romance with Reynaud Chevalier, “the son of a French nobleman and a Natchez princess.” Reynaud is also an enslaver, both in his “French” context as a land-owner of a prosperous Louisiana estate as well as in the context of the Natchez, with whom he and Elise live for at least half of the novel.

Holy shit, you, modern romance reader, may be saying to yourself. These characters are irredeemable, the only useful function for this book as kindling.

At first glance, one could and should question why this story centers the perspective of Elise, a French woman who begins the novel believing in some stereotypical ideas about the indigenous people even if she is more respectful of the cultural differences compared with her fellow colonizers. (It’s a low bar.)

Reynaud had tried to warn the arrogant commander of the fort of the imminent uprising, but of course this warning was ignored. Elise manages to narrowly escape becoming a casualty, but witnesses the death of many of her neighbors as she flees to the woods.

Reynaud takes on a small group of survivors in exchange for the nightly “bed-warming favors” of the beautiful widow, which he primarily puts forth as the condition to spite the assholes in the party who continue to cast aspersions on his motives and character despite him planning on helping them with no expectation of payment in return.

Reynaud isn’t a rapist, which is refreshing. He knows that her fellow survivors coerced her into accepting the stated conditions of his help, and he quickly realizes that Elise is scared to death of any sexual advances. A turning point in his gentling towards her is realizing that her aversion to him is not because he’s racialized as other (despite his French aristocratic father), but because of her own trauma at the hands of men.

Elise: problematique

Let’s focus on Elise. She’s, er….problematic.

Why would we want to inhabit her perspective throughout the narrative? Why should we feel anything but disgust for Elise? She’s a colonizer and an enslaver.

Yes, she is both of those things. Therefore it should be easy to place her in the “villain” category. She’s clearly a monster.

But Elise isn’t here by choice as a way to enrich herself. The binary of “villain” or “hero” presumes that people are either all bad or all good, or that there’s no nuance in considering the motivations and alternatives available for people who do objectively bad things.

Elise was falsely imprisoned in France by her jealous stepmother, and is transported at 15 to the Louisiana territory as a “bride” with other “criminal” women.7 Not only is she a literal child, she doesn’t even get to choose her husband once they arrive — her beauty is consistently a liability as she’s hand-picked as the wife (aka sex slave) for a violent drunk who’s owed political favors. We know that he violently rapes and assaults her for years.

She’s still a colonizer. That’s unambiguously wrong.

But what is she supposed to do? She’s a victim of circumstances beyond her control. Once her husband dies, she can’t go back to France — even if she could afford passage, she has no means to survive in France and could also be thrown back in jail for “escaping” her sentence in Louisiana.

She’s still an enslaver. That makes her evil…right? Discomfort accelerates.

There’s definitely a way to read this book as slavery apologia — it’s told from the perspective of the enslavers and there is zero problematizing by the text about the enslavement of Black Africans in a system of chattel slavery and minimal examination of the enslavement of indigenous people by both the French and the Natchez.

We can’t pretend like the author isn’t playing a part in shaping the narrative and our perception of the choices made by the main characters. The book positions Elise’s treatment of her “servants” as different from the more villainous characters within the narrative, ignoring the inherent violence of chattel slavery and encouraging us to read her as a benevolent boss.

But what do we want Elise to do, to show that she’s not a villain? Can we acknowledge that while she maintains privilege in this situation as a property-owning white woman that she is also a victim?

Elise inherited the farm and the enslaved people when her husband died, and it’s not a flourishing estate. I’m not sure if Elise even has the power to free the enslaved people, but if she did she would certainly be consigning herself to death, and likely them as well.

This situation isn’t purely confected. It’s a historical fact that throughout history, people found themselves in situations where through no deliberate action of their own, they became enslavers. Every point after that they are making choices, but it’s naive to position these choices as without harsh consequences.

What would you (I) do?

Fiction that transports us asks us to put ourselves in the shoes of the protagonist, and experience the world through their eyes.

On the one hand, it’s quite easy to immerse myself in Elise’s perspective and see the world through her eyes. I see the complications of the world, I understand how she’s come to believe what she does about the world, and I understand the choices she makes within her understanding of what choices are available to her.

But when I come back to the world I live in, the world in which I would never, as if that speaks to an inherent goodness or moral rightness on my part, instead of a result of the fact that I live in a world in which I don’t have to make those choices…

It’s uncomfortable. It’s horrifying: not because I read about Elise doing it, but because I’m no longer sure I wouldn’t do it, too.

Old skool, problematic romance

I feel like I need to be 800% clear that I’m not trying to argue that Fierce Eden isn’t problematic. It is problematic, to the hilt.

It’s also a very compelling romance.

It’s also very transporting, and I came away with a much deeper understanding of a time period and culture I knew very little about.

The book goes deep into the culture of the Natchez, and presents Natchez characters as individuals with their own differing motivations and characteristics (i.e. the opposite of a stereotype).

Despite the Natchez killing literally an entire fort of French people, including children, Elise, and the narrative, does not demonize the indigenous people as a group. While Elise is realistically traumatized, she does not turn that trauma into an excuse to dehumanize them based on their race or nationality, even before she spends an extended period of time living in the Natchez community.

I enjoyed this problematic book.

I enjoyed this problematic book.

There, I said it.

I enjoyed it, both the first time I read it 20+ years ago and also as a 36-year-old woman in 2023 who’s learned a lot about more about critically engaging with texts.

I know I’m not supposed to like it.

I’m supposed to shudder at this book’s existence, brand it as racist, consign it to romance’s problematic past, and talk about how I’m so glad that romance is better now. Because after all, we are on that slow march of progress towards everything getting better: a linear path up and to the right.

The thing is, I’m not sure that stripping away the problematics is making historical romance, in this case, better so much as it’s allowing readers to look away from history, and allow us to maintain the comfortable fantasy that people who do bad things are evil monsters, and therefore we would never.

The Regency: a safe space for escape?

If we want to avoid having to look at any problematic history, why not create a place where that unpleasantness doesn’t exist? Or at least where we can pretend it doesn’t exist?

Our idea of the Regency is mostly made up (hence Hallock’s use of “chronotope”), but we imagine we understand what it was like, because the texts we consume repeatedly erase the inconvenient truths that would disrupt the fantasy of unproblematic wealth and privilege.

It helps that our education system aids and abets this agenda, by woefully neglecting to educate most of us about how closely colonialism, capitalism, and white supremacy are tied together.

Hallock covers some of the historical inaccuracies that get brought up the most in romance discourse:

Everyone (who’s worth talking about) is titled (or will be by the end of the story) — about half of the top-selling romances in a 6-month period in 2017-2018 had Duke, Duchess, Marquess, or Earl in THE TITLE.

Nobody (heroic) has syphilis despite 8-15% of the general population having it at the time, and romance heroes being notorious for sleeping around indiscriminately.

I’ve also seen discourse about how convenient it is that the protagonists have a potentially ahistorical view of and access to bathing, and they often have straight, shiny white teeth despite eating lots of sugar in a time before modern dentistry and orthodontics.

Everyone is handsome/beautiful, the idle rich aristocrats have 6-pack abdomens as a result of riding horses, and their worldviews are decidedly modern.

These are the innocuous inaccuracies.

The more insidious inaccuracies have to do with what is hidden from view completely, not what is just improved upon.

Everyone is rich, but nobody talks about where the money comes from

Slavery was outlawed in England in 1807 — just before the Regency period! That doesn’t mean people in the Regency had clean hands when it came to the exploitation of people of all races.

Wealth accumulated in this period was likely to be the result of investments in colonial activities such as subjugation of India to control trade and resources, plantations in the West Indies that exploited enslaved people to harvest sugar in brutal conditions, and profiting directly from the Atlantic slave trade.

This doesn’t even get into exploitation on British soil of tenants under feudalism and harsh working conditions in coal mines, or the Highland Clearances in Scotland.

There’s recent research that shows that many of the advances in technology and necessary resources that fueled the industrial revolution are tied to slavery: “The forces set in motion by the slave and plantation trades seeped into almost every aspect of the economy and society.”8

(Sorry to inform you of this: the new vogue of Victorian industrialists don’t get to wash their hands of the problematics, either.)

Land-owning Regency heroes are diligent landlords who put the good of their tenant farmers above their own pleasures, who work just as hard at their desks dictating correspondence to their secretaries as the workers do in the field, who deserve seats in Parliament deciding the fate of an entire country not due to the nature of their birth because they too understand the plight of the common man… and on and on.

We are never confronted with the inconvenient truths of how the Regency sausage is made because the meat grinding room doesn’t even exist. The sausages just exist.

An unproblematic space doesn’t exist

There are a million ways in which the collective world building of Regency romances create a supposed safe space in which we never have to stare too long into the abyss, and we certainly never find ourselves uncomfortable.

I think the gradual invasion and reshaping of Regency England to be historical space that can be deemed “unproblematic” shows our discomfort with the inconvenient truths of history.

As the Regency era was invaded by our romantic fantasies, romance readers and writers have colonized the historical space to become a sanitized and confected playground. Its purpose is to meet our need for an “unproblematic” space to play out the conflicts that are central for white women while marginalizing any conflict that could center the conflicts for other people.

This is why most Regencies focus our attention on gender inequality and the unfairness of marriage as the sole choice for economic security for women. It narrows the scope of the story to the focus on the impacts of the cisheteropatriarchy on white women, but often sidesteps attempts at intersectional understandings of oppression.

So many suffragettes, so few abolitionists.

And yes, you can certainly find outliers. I’m speaking in comically broad strokes because I think it’s disingenuous to shield the majority behind a few unrepresentative examples that allow us to preserve the fantasy that we’re getting better.

If I close my eyes, the monster disappears

I’m not saying you can’t have your escape, that we should wallow in misery.

But let’s be real: looking away is for our own comfort, and we don’t get to pat ourselves on the back for it. We don’t get to say that the stories we consume are getting better and less racist or less problematic just because we’ve stripped them of anything that makes us uncomfortable.

I think I’d much rather read about characters who are existing in a more complicated world, because their worlds are complicated in ways our own worlds are complicated.

We want simple worlds because we’d like to believe that we are blameless in our own worlds. We are all casually cruel in our self-serving focus on our own concerns and our indifference to problems that are too big for us to individually make a dent in.

This allows us to maintain the fantasy not just that we’re the heroes, but that it’s impossible for us to be the villains.

When we look away, it doesn’t make the bad things stop. It just allows us to stop caring.

I will not write an essay about Cartland. I will not write an essay about Cartland.

In an attempt to be brief and keep things moving, I’m massively oversimplifying quite a few things here.

What I’m gesturing at is that earlier historical romances that verged on the erotic, such as Forever Amber by Kathleen Winsor (1944) and Angélique by Seargeanne Golon (11 novels between 1957 and 1985), often had heroines who engaged in multiple affairs with many men, which provided many possibilities for titillation.

Even if the books ended with the heroine in or pursuing a monogamous relationship with a lover, the driving force of the narrative was not the formation of the couple, which would be expected in today’s historical romances.

I’ve tried reading other historical epics of the pre-1972 era, but found them so depressing and cruel that I tapped out before being able to construe a proper understanding of what they were doing.

I promise to dedicate a post to this in the near future, as I realize that despite my intense research into this period, I haven’t spoken about it much on Substack or in the podcast feed.

It’s hard to put a hard dividing line to delineate where things started shifting towards the Regency - that will have to be an investigation for another day.

My anecdotal experience is that starting in the mid-1980s, it became more common to find single-title historical romance set in the Regency. In the mid-1990s, historical Western American romances had quite a moment. By the time the Western American fad was not longer the rage, the market seemed to increasingly move towards Regency.

This is not nearly comprehensive, but I looked up a few household names to give context:

Some examples of authors who began writing single title Regency in the 1990s include Julia Quinn (1995), Eloisa James (1999), and Connie Brockway (1994).

Some authors still popular today got their start slightly earlier, in the mid-1980s. Lisa Kleypas first started publishing romance in 1987, and many of her earliest works were set in the Regency period. Mary Balogh (1985) and Loretta Chase (1987) also began writing Regency-set romances in the 1980s.

Catherine Coulter stands out to me as an author who made the jump from the earlier period of category-length Regencies, first publishing in 1978, to writing single-title Regencies in the mid-1980s, although she also wrote in other time periods in the 1980s and 1990s, and started writing contemporary FBI thrillers in the 1990s.

I’d recommend you read Hallock’s 3-part series on her blog, in which she covers research she presented at a IASPR conference: http://www.jenniferhallock.com/2018/06/27/history-ever-after-part-one/

In this context, she defines “chronotope” as a blend between The Literary Encyclopedia definition and her own expansion of the meaning: “‘A term taken over by Mikhail Bakhtin from 1920s science to describe the manner in which literature represents time and space.’ I am adding geography and ethnicity to this construct.” http://www.jenniferhallock.com/2018/06/27/history-ever-after-part-one/

This really happened. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/19/books/review/mutinous-women-joan-dejean.html#:~:text=Many%20were%20guilty%20of%20no,wilderness%20of%20French%20colonial%20Louisiana.

Slavery, Capitalism and the Industrial Revolution by Maxine Berg and Pat Hudson (https://bookshop.org/p/books/slavery-capitalism-and-the-industrial-revolution-pat-hudson/19633298?ean=9781509552689) - listen to a great podcast episode with them here: https://newbooksnetwork.com/slavery-capitalism-and-the-industrial-revolution

A very thought-provoking read. Like you, most of what I know of History is through media. But I feel like not much of it, especially in my region, shows the many shades of grey. It's either tragic or sanitized. I am learning so much from your articles. Cheers from the edge of the Atlantic.

I love my Regencies but this really made me think about why.