“I know it when I see it,” is a now infamous phrase that originated from a Supreme Court ruling by Potter Stewart, regarding the question of whether the material in the case was “obscene.”

The question “what is a romance novel?” tends to elicit a similar response.

Those of us who are Too Online can attest to a recurring brouhaha that happens whenever a writer boldly claims to have written a romance novel that transcends “tired” formulas by ending unhappily, or some such thing that appears to defy genre conventions to the extent that it’s not…the genre.

A common response by well-meaning romance readers is to quote some version of the RWA definition of romance fiction:

“Two basic elements comprise every romance novel: a central love story and an emotionally satisfying and optimistic ending.”

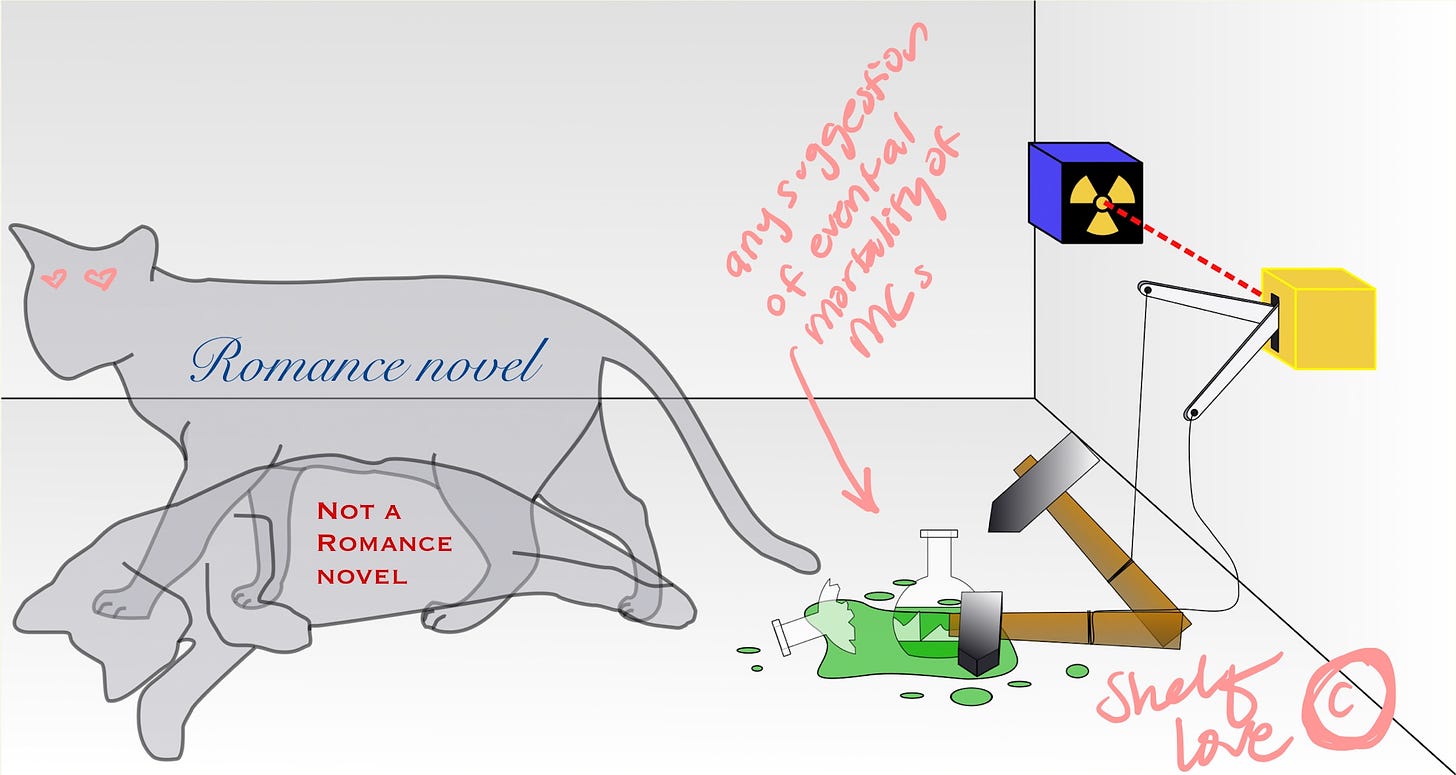

The issue with confidently using this definition as the last word is that there are so many assumptions inherent in applying it. What’s so obviously disqualifying to one reader can be invisible and unobserved to another, resulting in a Schrödinger's Cat Shouting Match (where both participants are simultaneously right and wrong).

What is a central love story? To be central, must the love story take up 51% of the pages or more? 75%? If we could agree to a percentage, how would one even calculate it? Only scenes in which the characters are together, or thinking of the object of their desire? How many scenes in a row without an interaction will we tolerate before the centrality of the love story wanes?

What is emotionally satisfying? What is optimistic?

What is the ENDING?! Is it what happens in the last scene of the story, or does it include our beliefs about what happens after the last page, based on what the story leads us to believe will happen? Does it include every possible thing we can imagine the characters will face in their lives, beyond what could be supported with textual evidence?

To me, this definition feels impossible to enforce, because of the unspoken assumptions we all bring into its application.

Most of the time the books shelved in a romance section align enough for the definition above to feel sufficient. Most of the time, the “definition” is safely tucked away but there’s no need to look too closely at its methodology.

But then there are times where I can’t QUITE place my finger on it, but it doesn’t FEEL like a romance to me. Is it just “unsuccessful,” that is, a poorly executed romance novel? When does a book rise to the level of being kicked out of the genre?

And more importantly — if there can be no clear consensus, if the definition is ultimately subjective, and dependent on a reader “knowing it when they see it,” are we leaving out other important dimensions?

Specifically: are romance novels defined purely by observable elements of a text, or by the feelings they elicit in the observer?

In effect, "I know it when I see it" can still be paraphrased and unpacked as: "I know it when I see it, and someone else will know it when they see it, but what they see and what they know may or may not be what I see and what I know, and that's okay."

“what it feels like”

“To qualify as a romance, the story must chronicle not merely the events of a courtship but what it feels like to be the object of one.”

— Janice Radway, Reading the Romance

Originally published in 1984, and written at a time when books marketed as romance novels published by major publishers were exclusively heterosexual pairings, Janice Radway’s ethnography of romance readers is still, almost 40 years later, the best, most thorough, er….ethnography, of romance readers that exists.

The first time I encountered “ethnography,” I looked it up and there’s no shame in that. Let me define it here in case this is also your first encounter or you need a refresher:

Ethnography is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. Ethnography explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject of the study.

Important to the thesis of this Substack article you find yourself reading, Radway focused on the READERS, and then backed her way into defining “The Ideal Romance” and “The Failed Romance.”

In other words: “I know it when I see it,” and “I know it when I don’t see it.”

Radway asked her 42 “Smithton” readers — all women who lived in an anonymous metro who frequented a bookstore staffed by romance influencer Dot — to rank order the importance of different narrative features in romance.

“A happy ending” was identified as the first most important feature for 22 of them, and 32 included it in the top three most important features.

Radway acknowledges that there’s a common understanding that the expected benefit of romance novels is that they raise the spirits of the reader. In other words, the process of feeling particular things during the reading experience influence their moods and bring about real change in their lived experiences.

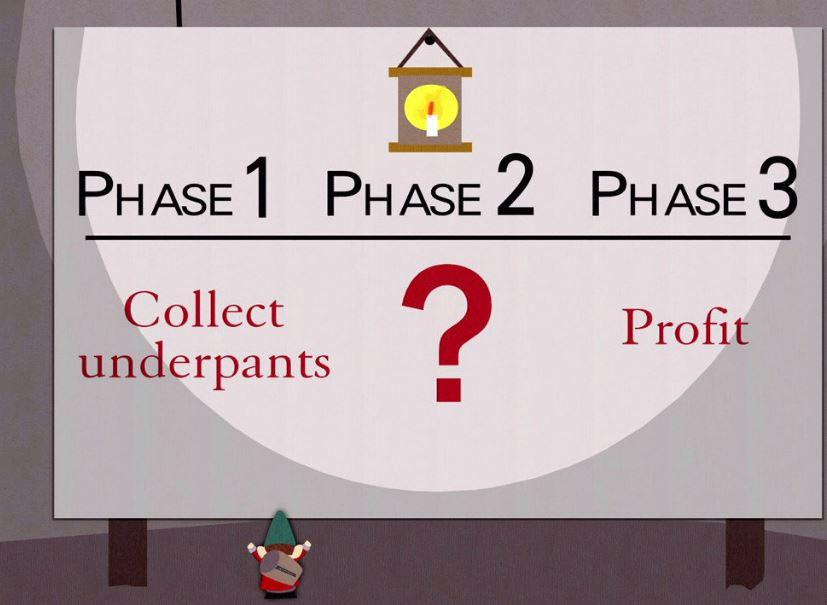

None of this is revolutionary for those of us who read romance. But let’s map out the logic of the basic definition of romance plus the basic explanation for why readers read them:

a romance novel is defined by a happy ending

?

a happy ending makes readers feel good

…WHAT makes them feel good? What makes the ending happy? It feels like we’re missing a critical piece of information here.

Cause and Affect

Thankfully for us, Radway conducted extensive interviews with her participants, which means we get to learn more about what feeling the readers expected in order to earn a happy ending.

Radway observed that while it couldn’t be defined as a defining feature for romance, many readers did not feel the ending was successful when the love story was rushed, and not depicted as a gradual process unfolding throughout the story.

For example,

“…the Smithton readers are not convinced when a hero decides within two pages of the novel’s conclusion that he had been mistaken about the heroine and that his apparent hatred is actually affection. Dot’s customers dislike such ‘about faces’; they prefer to see a hero and heroine gradually overcome distrust and suspicion and grow to love each other.”

It’s not just a central love story that defines a romance, then — it’s a central romance that is explored and resolved in a particular way that allows the reader the satisfaction of feeling like they’re a part of the romance.

It’s not just a happy ending that defines a romance, then — a happy ending is the result of feeling the romance experience is satisfying to them.

Dot’s customers acknowledge, “what they enjoy most about romance reading is the opportunity to project themselves into the story, to become the heroine, and thus to share her surprise and slowly awakening pleasure at being so closely watched by someone who finds her valuable and worthy of love.”

It’s a feeling, and while there can be some consensus on narrative elements that commonly elicit those feelings, there are also bound to be elements that break the fantasy for other readers, or prevent others from successfully projecting themselves into the story, and vice versa.

An Abrupt “About Face”

I apologize for the abrupt ending, but I’ve realized I don’t have a happy ending to resolve the ideas that I’ve folded open here. And perhaps that’s because I don’t think this is really the ending of this particular topic…

…stay tuned for more!

Further reading:

Angela Toscano collected the many definitions of romance across a variety of (primarily) scholarly sources on Teach Me Tonight

One thing that kills the HEA is when one of the MCs has behaved badly, and does not grovel or otherwise atone for their behavior. I feel like they don't deserve the HEA, and the other MC is making a bad decision by choosing them.