It’s a truth universally acknowledged that a great story must be in want of adaptation to other formats. After all, if we love it in one format, why should we not love it in another? (Ha! The gods of media laugh at this assumption!)

While this truth predates the age of film and even novels (it is, in fact, universal), for the sake of brevity and my particular interests, I’ll limit this conversation to film adaptations of romance novels published as books.

Film adaptations of romance novels reveal why the romance novel as a genre is inextricably linked to their format, the novel. By thinking through romance adaptations, we also make legible our generic expectations for romance novels themselves, tied to the distinct and predictable pleasures offered by the experience.

The History of Romance Novel Adaptations

An early example of a book legible to modern readers as a romance novel was The Sheik, a 1919 bestselling novel by E. M. Hull.1 Modern readers may also find it abhorrent, due to the orientalist and imperialist themes, to say nothing of the explicit rape of the kidnapped heroine by the hero, but that is a conversation for another day.

Modern readers may think that the popularity of the book means readers at the time weren’t aware of the problematics — but they were. Remember how 50 Shades of Grey was both a huge bestseller and also lambasted by readers and the media?

Some of the objections from the time are familiar to modern readers, while some were rooted in the cultural context of the time.

According to always excellent Hsu-Ming Teo in her comparison between the British novel and the American film:

The Sheik elicited a polarized and visceral reaction upon publication in 1919. Billie Melman (90) has claimed that its sales surpassed all other bestsellers at the time; yet while it achieved instant cult status among its mainly female readers, contemporary literary critics and the self-appointed guardians of social morality were appalled, dismissing it as “a typist’s daydream” and condemning it for its overt portrayal of sadomasochistic sexuality—a response that has been repeated by feminists throughout most of the twentieth century (Melman 90).2

It was a no-brainer that The Sheik would quickly be adapted for the celluloid screen. While film had evolved as a technology towards the end of the 19th century, commercially-available silent film had been gaining steam and was hitting a high in the 1910s.

Novel vs. Film: Different Formats, Different Choices

The Sheik, the silent film, was released in 1921 and featured Rudolph Valentino as the titular character with Agnes Ayres playing his vict… I mean, love interest, Lady Diana Mayo.

The question then, was how would the film handle the sexual violence of the original text? The romance novel’s appeal seemed closely tied to the titillation it offered audiences: it indisputably made them feel things, even if all those things weren’t uniformly or unambiguously pleasant.

But novels and films are different formats, with both different legal, commercial, and technical boundaries and opportunities to impart their meaning.

Teo’s analysis describes how the abduction mirrors the original text, but the rape is deferred in the film. Viewers educated on the novel were more likely to read between the lines of the opaque symbolism to interpret a rape where none happens on screen.

Those who were familiar with the novel inferred the rape because the following caption, “Through the dull slumber of despair—until morning tempts back a desire to live” seemed to suggest the same plot as the novel, as did Diana’s subsequent costume as a subdued Arab woman. In Kansas City, the widespread understanding that Diana had been deflowered led to the film’s ban locally (Leider 166). However, other audiences concluded that Diana was not raped.

In the era before the Hays Code, Hollywood was still subject to censorship, albeit mostly via an overwhelming number of local ordinances, which were confirmed as legal in a 1915 Supreme Court ruling that determined motion pictures were purely commerce and not art, and therefore not protected as free speech by the first amendment.3

Teo notes the impact of censorship concerns on the adaptation:

This ambiguity in interpretation [of the rape] was very much due to the fact that Lasky [the producer] wanted the film to evade the censors so that it would be as “mainstream” and popular as possible (Leider 162, 167). As Steven Caton4 has argued, the film can be interpreted as a shift from rape to romantic courtship.

Social historian Carol Dyhouse also wrote about the differences between the novel and the film in her book Heartthrobs: A History of Women and Desire (drawing on Teo’s work). Dyhouse wrote about Valentino in the context of his heartthrob status, and so it’s no surprise that the casting of a beloved actor with a pre-existing characterization in the audience’s imagination also influenced his on-screen characterization.

She also explored how the visual format created different opportunities for creating meaning:

Much of the sexual charge loaded into the original text is displaced, in the film, onto the weather: winds batter and rage, and sandstorms swirl. Rudy projects an endearing tenderness throughout.5

Where the novel had powered the audience’s imagination with prose, the film stimulated their visual senses.

The Sheik was just the start of the beautiful, and sometimes lucrative, relationship between romance novels and film adaptations of romance novels

Great Genre Expectations

Genre expectations are organically formed by readers in their own minds. (Even if an authority claims to be defining the rules, what they’re actually doing is putting into words retroactively what already exists based on sociological or textual dissection.)

Romance readers come to expect a predictable experience from romance novels after reading more than a few, and noting what’s shared between books in the genre and being able to parse out elements that are specific to a particular book.

But at the end of the day, readers are chasing a feeling, not the common features that tend to elicit those feelings. Readers don’t want a quarter inch drill: they want a quarter inch hole in their heart.6

Showing vs. Telling Feelings

In her book Making Meaning in Popular Romance Fiction,7 Jayashree Kamblé uses adaptations to illuminate what distinguishes a romance novel. Kamblé’s analysis illustrates the differences between the formats of novel and film and how that impacts the consumer's experience of the romance.

Kamblé’s thesis can be summarized as:

Romance novels: tell events and show thoughts and feelings

Romance films: show events and tell thoughts and feelings

While a novel may thus contain a description that forces readers to exclude some of the items in their mental storehouse of visuals, it leaves the final image to them. Movies can not replicate this novel trait of flexibility in adopting various narrative styles and moods in the same way. (page 7)

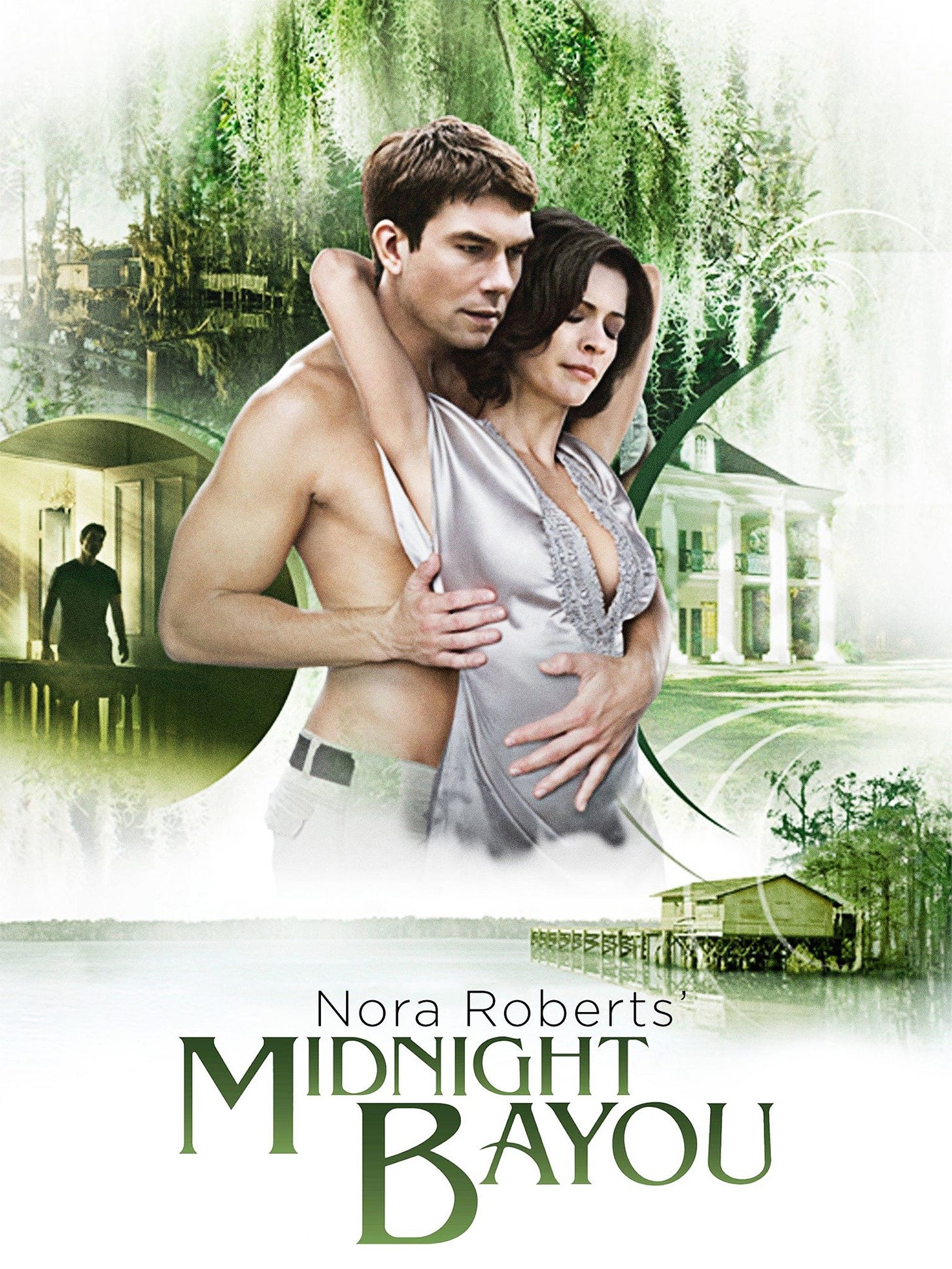

The example that she uses to illustrate this point is Nora Roberts’s 2001 book Midnight Bayou, which was adapted into a 2009 Lifetime made-for-TV movie.

What is most significantly novel about the romance novel Midnight Bayou, however, and absent in the movie text, is the use of perspectives of point of view that can tap into interiority, particularly through the narrated monologue, which is Dorrit Cohn's term for quote "a character's mental discourse in the guise of the narrator's discourse." Cohn talks about the narrated monologue as a narrative style where a character's interior voice is retained in the third person perspective that is usually employed by an omniscient narrator." (page 7)

Next, she discusses a scene with its "multiple modes of representing consciousness performs a triple function. It allows the reader access to what [the character] feels [the metaphor of being hit by a sledgehammer] and thinks [she is beautiful and familiar.]"

In an adaptation, you gain visual and auditory stimuli, and a host of related connotations — however you also lose the pleasure in thinking and feeling another person's thoughts and feelings, which the novel enables.

Can Adaptations Give That Romance Feeling?

The 2005 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice provides a good illustration of how romance films can use what Hollywood gave them to evoke the feelings a romance genre reader expects using the visual format.

Keira Knightley and Matthew McPhadden play Lizzie and Mr. Darcy, and in a memorable ball scene, they dance while having a conversation that escalates from mild to emotionally tense.

The film shows them dancing in a crowded ballroom, which we can hear and see, even as we know we’re immersed in Lizzie and Darcy’s experience by the visual and auditory focus on them amidst the orchestra and dancers.8

We can hear the emotion in their words and see it on their faces, but then the film uses the visual format to immerse us even more in the perspective and interiority of our romantic leads. Now Lizzie and Darcy are dancing alone in an empty ballroom, aware only of each other.

While the movie doesn’t literally include the interior thoughts of our protagonists, the audience is shown their feelings: they are no longer aware of anything else other than the object of their romantic desire and ire, and what we are shown mirrors that.

While a novel could show us these feelings by writing “she felt as if the world faded away and they were the only two people in the ballroom,” this film is extremely effective at showing emotions within the bounds of the format.

I think that P&P 2005 is a successful “romance adaption” because it gets as close as possible to showing the feelings that I am looking for when I open a romance novel.

What makes a successful romance adaptation?

For the sake of this post, I’m going to use this framework to define the success of a romance novel to film adaptation:

Execution: Cross-Format Genre Expectations

Does it maintain the romance novel feeling as much as possible in the film format? In other words, is it trying to meet my expectations as a romance novel reader?

Cultural Translation: Adapting to Audience Expectations

Does it use elements of an original romance novel text and translate ideas to increase relevance to the audience in a particular culture and/or time?

You’ll note I’m not that interested, personally, in the faithfullness of a film in “accurately” portraying the specific text.

Using this framework, Pride and Prejudice (2005) does an excellent job of using Execution to meet my needs as a romance novel reader who wants to feel all the longing, angst, and pining I love in romance novels.

It also works to translate the story to an audience that is two centuries removed from the world in which the novel was written, by allowing us to both immerse ourselves in a world that is different from our own but making concessions to modern sensibilities and language.

For example, Jane Austen’s text does not include any on-page kisses, however the 2005 film pulls back the curtain on their intimate relationship by creating a scene not in the novel, in which Lizzie and Darcy share a romantic moment and kiss post-marriage.

Cultural translation accomplished!

Putting the Framework into Practice…

Now that I’ve covered the historical and theoretical foundations… I realize that this post has gotten rather long. So, stay tuned for my next post on adaptations, in which I’ll talk more about recent romance novel adaptations and how successfully (in my opinion, of course) they captured that romance novel feeling.

The evolution of ideas…

I’ve thought about adaptations quite a bit over the years, and while this post is touching on some topics I’ve discussed previously, I think it’s also an evolution that is developing in new directions. Here are some threads I’m pulling on in this post:

I did an episode a few years ago that was related to the renewed chatter about the viability of romance adaptations based on the excitement for Bridgerton. In that episode, I talked about my reservations about adaptations based on how film adaptations of romance novels tend to disappoint me because I’d rather just read a romance novel! I also discussed the commercial side of adaptations, and asked “who profits from ‘diverse’ romance adaptation?”

I was also recently a guest on Pod Culture Oz talking about adaptations (more generally, but you know *I* was talking about romance!). In thinking about what I was going to share I came up with the framework that I’ve presented here. I’m looking forward to stress testing how useful it is as I continue this exploration in talking about specific texts!

I finally released an episode about The Flame and the Flower that I recorded in May, and as I was writing this post today I realized that some of the things I worked through there about what readers were thinking in 1972 was coming through in The Sheik section.

Increasingly, I’ve been thinking about how there’s a tendency for modern audiences to think that readers (and people more generally) of the past are basically aliens who were completely oblivious to the “problematics” that bother us today.

Shortly after I recorded that episode, I actually wrote this Substack post that continues my ongoing journey to explore reader expectations and how reality is, like, subjective, man.

Closing Thoughts

I hope you enjoyed this post!

Now that summer is over, I’d like to get into a more consistent schedule with posting (and podcasting), but I’m also trying to be gentle with myself, remembering that this is fun and not one more obligation, and focusing on quality over quantity.

The Sheik is discussed at length in Hsu-Ming Teo’s Desert Passions: Orientalism and Romance Novels. Whoa!mance also did a series of podcasts on desert romance, including an episode on The Sheik.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mutual_Film_Corp._v._Industrial_Commission_of_Ohio , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Film_censorship_in_the_United_States

Caton, Stephen C. “The Sheik: Instabilities of Race and Gender in Transatlantic Popular Culture of the Early 1920s.” In Noble Dreams Wicked Pleasures: Orientalism in America, 1870-1930. Ed. Holly Edwards. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000. Print.

Heartthrobs, by Carol Dyhouse, page 28 https://global.oup.com/academic/product/heartthrobs-9780198765837?cc=us&lang=en&#

This is a riff on a common marketing-ism from Harvard Business School Professor Theodore Levitt: “People don't want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!" I say this at least once a week at work, because it never fails to capture the crucial idea that audiences don’t want features, they want benefits. https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/what-customers-want-from-your-products

Kamblé, Jayashree. (2014). Making meaning in popular romance fiction: An epistemology. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1057/9781137395054

As I searched for gifs, I stumbled on this blog post that includes many more moments from the movie that could be discussed: check it out!

You really nailed it with the P&P example they "showed" emotions in a way that so many romance movies just don't get right. The Darcy Hand Flex is iconic because it evokes so much feeling!!

Loved this article! In the same way that thinking about adaptations helps us to reflect on romance novel expectations, I felt like this article made me reflect on romcom movies beyond adaptations & some of your points made me think about what’s missing from the current romcom releases. Can’t wait for the post on contemporary adaptations!!