Gender All The Way Down: The Romance Genre

Moonstruck Madness and the androgynous woman-child "brat" in romance novels

I started this essay thinking I was going to talk about brats in romance novels, and then realized that a woman is considered a brat, in other words a “badly-behaved child,” when she exhibits masculine-coded traits without the benefits of gender privilege.

Le sigh. Why does it always seem to come back around to gender?

It’s hard to discuss romance novels without talking about gender, or risk feeling like I’m omitting a crucial point if I don’t address gender.

But, to only study romance through the lens of gender feels reductive, repetitive, and boring. Why does it seem I (we?) can never get away from it?

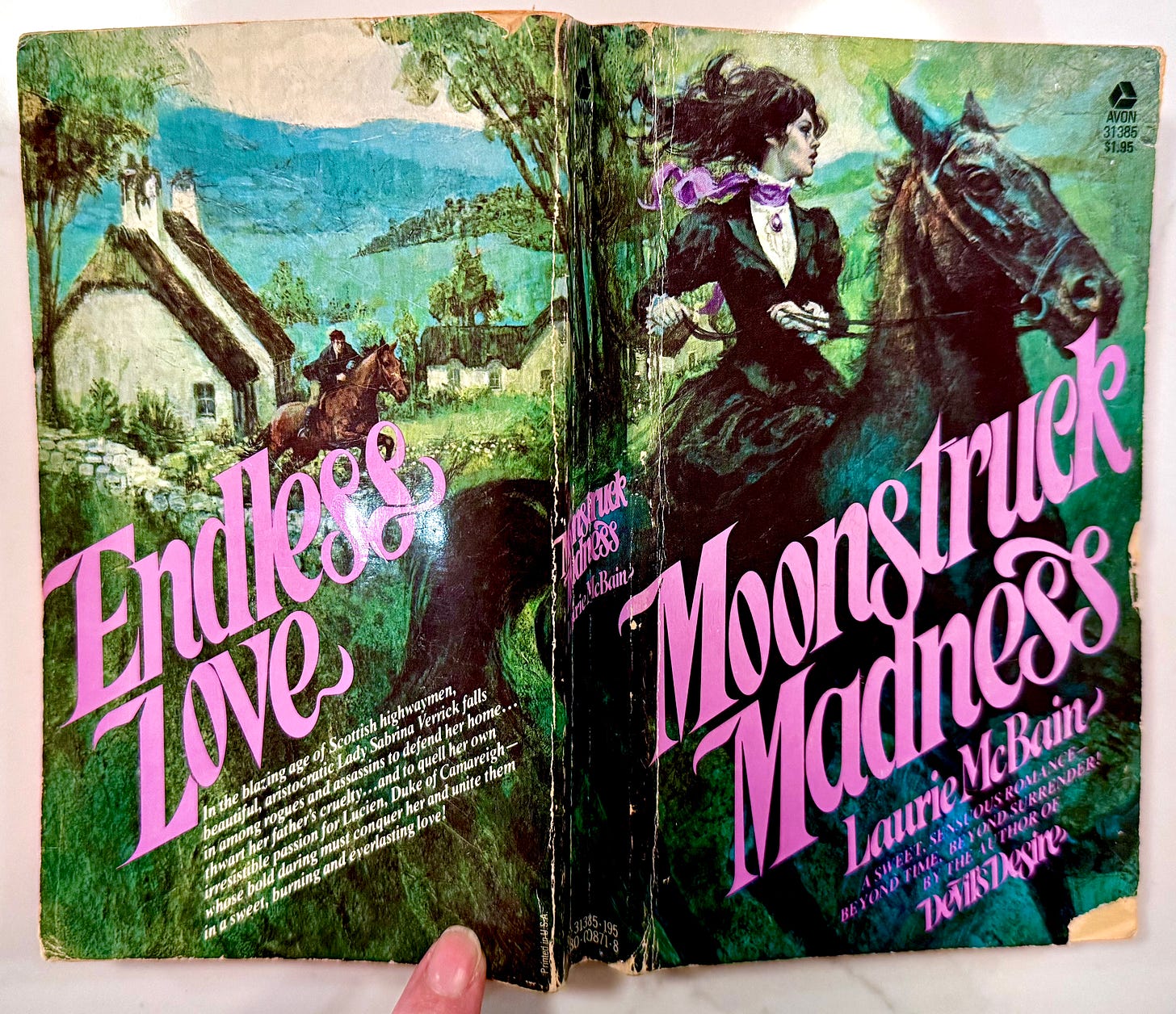

Over the course of a few posts, I’d like to talk about Moonstruck Madness by Laurie McBain, a bestselling romance novel published in 1977 by Avon, the obsession with exploring gender in romance (by authors, readers, and scholars), and the challenge of understanding ourselves through our desires.

Part 1. Moonstruck Madness by Laurie McBain

Moonstruck Madness debuted on the New York Times Mass Market Paperback Bestseller List at #3 on February 27, 1977, the same week Carrie by Stephen King listed at #7. MM bounced up to #2 in March and remaining on the list throughout 1977. A year after its debut, New York Magazine reported there were 1.8 million copies in print.

I mentioned McBain briefly in my last post about bestsellers (Why is Fourth Wing Popular?), as she was one of the bestselling “erotic historical romance” authors of the 1970s.1 McBain’s first novel, Devil’s Desire, was published when she was just 26, and became a bestseller.

Moonstruck Madness was McBain’s second book — I’d seen it written about with high praise in contemporary sources, so it seemed like a good place to start as I set out to better understand the appeal of the erotic historical romance of the 1970s.

The plot

Sabrina is a half-English/half-Scottish girl who grew up in Scotland with her grandfather, the chieftain of a clan that takes heavy losses at the 1746 Battle of Culloden. She narrowly escapes the massacre, fleeing to their dilapidated family manor in England with her siblings and aunt.

Abandoned financially and emotionally by their destitute but titled English father, Sabrina hatches a plan to become a highwayman named Bonnie Charlie, masquerading as a dapper Robin Hood-eque Scotsman to steal from the rich to support her family and eventually the locals. She doesn’t join with highwaymen - she is the highwayman, and recruits and leads a loyal crew. The story opens a few years into the scheme when Sabrina is 17.2

Lucien is a golden-haired Duke™ with a sexy/scary scar on one cheek, passing through the countryside where Sabrina lives. He first meets Sabrina as Bonnie Charlie and he is pissed that he has to sit by and be robbed. He vows to put an end to Bonnie Charlie and sets a trap, which Sabrina falls into.

Lucien is ready to kill Bonnie Charlie until he runs the bandit’s shoulder through with his sword3 and discovers that he’s a she — a raven-haired, violet-eyed beauty, in fact. Overcome with lust, I mean, paternalism, he nurses her wounds and tries to get her to reveal her identity so he can help keep her out of trouble, while she plots her escape.

In adjacent scenes, they both silently vow to seduce the other to achieve their goals. After a false start where the virginal Sabrina gets cold feet, they have a mutually-pleasurable and consenting sexual experience that ends with Lucien vowing to set Sabrina up as his mistress so he can “take care of her.”

Sabrina has no desire to be taken care of by a man when she can do it on her own, and easily escapes.

Lucien has to marry soon or else he’ll lose his inheritance to his terrible cousin, per his grandmother’s decree. Conveniently, to prevent Lucien’s inheritance, his terrible cousin kills his fiance Blanche and also tries to kill Lucien multiple times.

Sabrina’s father returns from Italy and decides to capitalize on his daughters’ beauty by marrying them off to the highest bidder. After Lucien realizes Blanche is probably dead, and spots Sabrina at a ball — revealing she’s of his class and actually a suitable marriage partner for him — everything falls into place for him to force her into marrying him (to appease her father, meet the requirements for his inheritance, and also because she’s pregnant!).

More drama ensues — the book is longer than it needs to be — and Sabrina resists Lucien’s domination until the end, slipping through his fingers so frequently that he seems to forget to be mad about it.

Sabrina, the brat

Sabrina isn’t called a brat, but she’s coded as a brat. Everyone loves her anyway — they acknowledge that she’s a product of her trauma and circumstances. She’s outspoken and aggressive, independent and confident, defiant, strong, and determined.

As I mentioned in my introduction: her brattiness tends to be attributed to childishness and poor behavior by some characters in the text. But when you take a look at the attributes above — aren’t those just masculine-coded traits? When she’s in drag as Bonnie Charlie, don’t those same traits transform her into the epitome of masculinity?

What I found particularly interesting is how McBain writes Lucien’s response to Sabrina’s brazen, often reckless actions and her cross-dressing evening activities in contrast with his fiance Blanche, who is ultra-feminine and displays no masculine-coded traits. Early in the text, Lucien indicates that Blanche, handpicked by his grandmother the Duchess (an archetypical tough old bird), is put off by his scar:

The Duchess snorted. "In my day— Well, that's past, but the fancy pieces strutting about today have no spirit. A lot of lace and pretty bows are all they are made of. No sense of adventure in them," she complained contemptuously, then catching Lucien's smile demanded, "Well, what are you grinning about?'

"Oh, just that I wish you and a certain person could've had the opportunity of meeting."

"A woman, eh?" the Duchess guessed.

"Very much so; however, I've seen her wield a rapier, sit a horse and scare the wits from twelve men so well that you might be doubtful of her sex."

The Duchess chuckled. "Sounds like quite a woman.”

—Moonstruck Madness, Laurie McBain (page 172)

Y’all — Lucien clearly loves that Sabrina’s a badass. The language he uses indicates her badassery and swagger are masculine traits at odds with her womanhood, but the Duchess sees no conflict with these attributes being praised in a woman.

Sabrina’s “masculine” swagger is a running joke in their marriage, and they continuously poke at how it defies gender norms:

"Shall we have a daughter or a son, I wonder?"

Sabrina gave him a provocative look. "You wouldn't allow me to have anything but a son, so he can swagger along in your disreputable footsteps."

Lucien's chest rumbled with laughter as he returned her look archly. "Me, swagger? I have seldom seen a pair of female hips swagger so! Be careful or the child will be come seasick."

Sabrina giggled happily…

—Moonstruck Madness, Laurie McBain (page 302)

Sabrina is not transformed by her marriage or pregnancy into a docile wife.

I forgot to mention earlier (oops) that she loses her memory for a bit, and therefore doesn’t remember why she’s angry at Lucien and resisting their father-enforced engagement, allowing them to marry and be blissfully happy for a while.

…until Sabrina’s memory returns, and she’s more pissed than ever that he overrode her free will and autonomy and took advantage of her when she was vulnerable. Lucien understands he did her dirty, especially as he’s madly in love with her and knows her well enough to understand why she sees this as the ultimate deal breaker.

As a result, he initially doesn’t lash out at her defiance and anger, continuing to view her brattiness (i.e. display of both feminine- and masculine-coded traits) with fondness:

Lucien laughed at the Duchess’s surprised face. “…Never have I met such an obstinate chit as Sabrina.”

“I can see you shall have your hands full managing your Duchess, Lucien, for once she has defied you and gotten away with it, you will never have complete control of her again—unless she wishes it, of course,” the Dowager Duchess advised with a glint in her eye.

“Defy me?" Lucien asked incredulously, giving Sabrina a sardonic glance. "She wouldn't think of doing such a thing, would you, Sabrina, my love?"

Sabrina clenched her hands beneath the folds of her gown. "Think of defying you, Lucien," she said with a sweet smile. "Why, I've never given it a thought—I just do it."

Lucien held up his hands in surrender. "You see, Grandmère, I haven't a chance.”

…The Duchess smiled, thoroughly enjoying herself.4

—Moonstruck Madness, Laurie McBain (page 344)

McBain is very aware of hegemonic gender roles, and she uses her characters’ responses to Sabrina’s performance of both ideal masculinity and ideal femininity to trouble the gender binary: what if Sabrina is feminine AND masculine, rather than feminine OR masculine?

In other words, Sabrina is androgynous. I’ve always interpreted “androgyny” to mean an absence of overt gender performance, but I looked it up and it turns out it’s defined by displaying (or identifying with) multiple genders.

Psychological androgyne

The erotic historical romances of the late 1970s were “perhaps the most significant evolutionary generation in the history of the romance novel,” according to Carol Thurston, in her 1987 scholarly work The Romance Revolution. She describes them as portraying “a specific kind of love, one that frees respect and the right of self-determination from gender” (Thurston 86).

Thurston believed that this was the driving force behind an increasing number of readers’ interest in these romances in this period.

The heroine—by definition the paragon of virtue — cares about herself, about her own wants, needs, and goals in life, yet she is never depicted as selfish… The result is that the customary happy ending now is possible only through the heroine’s emergence as an autonomous individual, no longer defined solely in terms of her relationship to a man.

—The Romance Revolution, Carol Thurston (86)

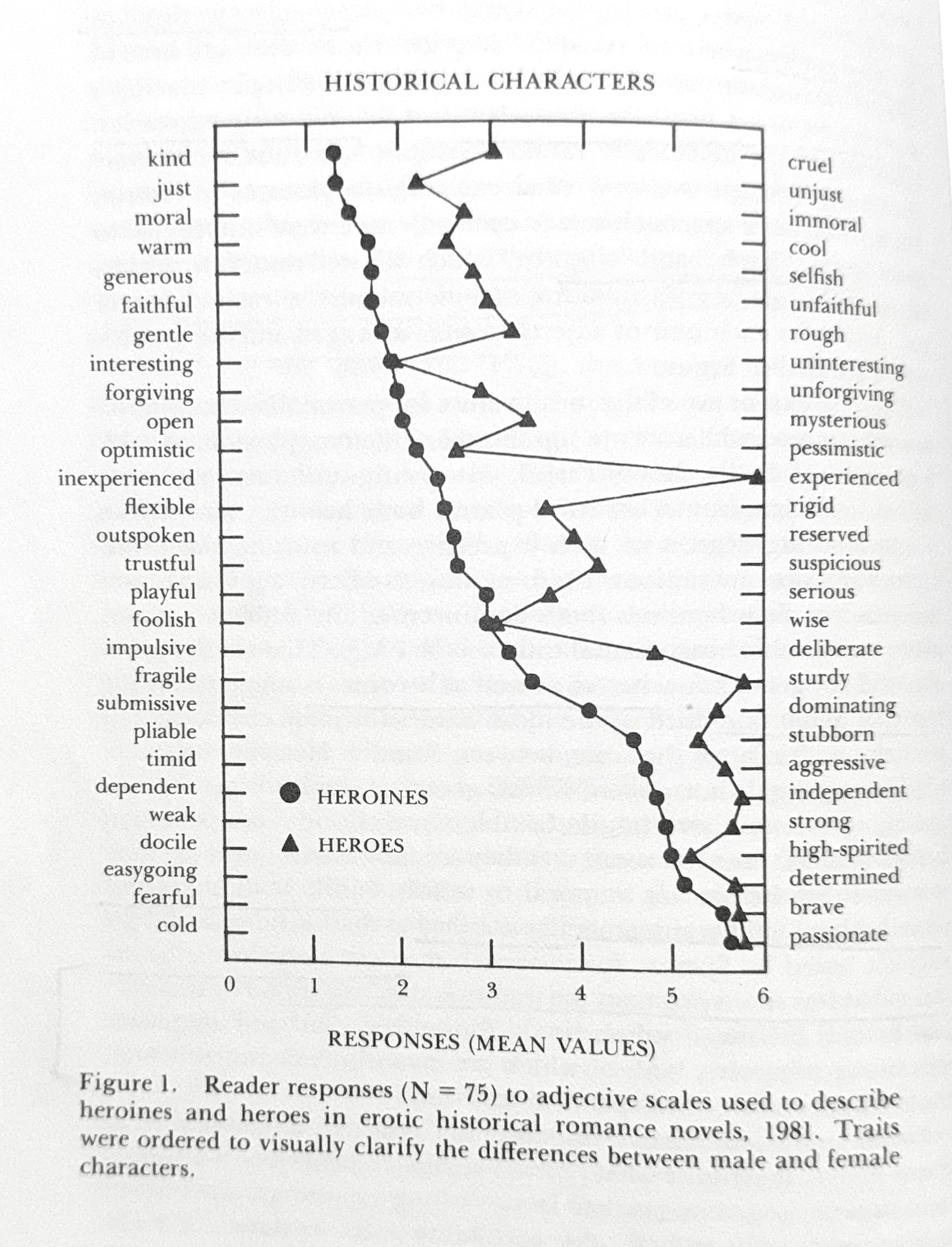

Thurston’s hypothesis was based on research she did with 75 romance readers, asking them to rate how romance heroes and heroines in books from from 1972-1981 adhered to stereotypical gender roles. She leveraged Sandra Bem’s Sex Role Inventory (BSRI) tool for the measurement.

Bem’s work suggested that: “subjects who score high on both dimensions [masculine- and feminine-coded traits] are considered psychologically androgynous… individuals with the highest levels of both feminine and masculine personality traits have higher levels of self-esteem and are exceptionally well-adjusted” (Thurston, 82).5

The prevailing theory in psychology prior to this was that the most masculine men and the most feminine women would have higher self-esteem/mental health, neglecting to consider the impact of also displaying traits prized in the “opposite” gender in a binary gender model.

Thurston’s work found that, among the the books studied published between 1972 and 1981, it wasn’t just about enabling the heroines to achieve well-adjusted psychological androgyny — the heroes also acquired the feminine-coded traits in addition to their masculine-coded traits:

The men with whom these women fall in love are strong-willed but not invincible, physically or emotionally. They are sensitive and capable of showing emotions — exhibiting the very traits they admire in women— if not in the beginning then through learning, loving, and understanding.

—The Romance Revolution, Carol Thurston (86-87)

Moonstruck Madness was published smack in the middle of this period, and Sabrina and Lucien epitomize the phenomenon Thurston is describing. Lucien’s emotional growth comes with learning that loving an androgynous partner means that he must also evolve his own beliefs and behaviors, and perhaps reevaluate his idea that Sabrina is acting like a brat, i.e. a badly-behaved child.

The woman-child brat

Earlier, I mentioned that Lucien is initially patient with Sabrina and her anger once she learns he took advantage of her temporary memory loss to maneuver her into marriage. Sabrina holds on to her stubbornness and desire for independence (masculine-coded traits), even as she begins to acknowledge she’s not helping matters and wishes they could resolve the rift between them.

To be fair, she has her pride: he made a fool of her, and she fears he was laughing at her declarations of love, wishing her to once again be an “acquiescent, loving bride.” It’s not like Lucien ever apologizes or atones, although he does try to give her space and time to cool down.

His patience wanes after a year when Sabrina angrily confronts him with a rumor that he’s been unfaithful — it’s not true, but he cynically implies it may be.

Lucien stared at Sabrina's angry face. "I thought time would change things between us. That maybe with the birth of our child you might soften a little, but no, you're just as tough as ever, aren't you, Sabrina? I'm beginning to think it really isn't worth it. I doubt you'll ever grow up."

Sabrina stared at his back as he walked to the door, feeling like calling out for him to stop, when he turned and said, "I believe I will take your advice. A change of scene would do me good. I begin to grow tired of your frowning face and sulking moods. I want a woman, not a little girl."

—Moonstruck Madness, Laurie McBain (page 353)

Lucien, frustrated with Sabrina’s refusal to forgive him before he’s ever apologized, equates Sabrina’s stubborn yet righteous anger with childishness. He’s ready to move on, but she continues to hold him accountable for his actions.

According to Lucien, a “woman” would do all of the emotional work to repair the rift that he created. A “woman” would be kind, generous, forgiving, putting his emotional needs and desires before her own selfish — “childish!” — desire for him to atone.

Lucien’s paternalism is showing — his emotional needs are logical and valid, but her emotional needs (particularly when they conflict with his) are irrational and childish. He knows what’s best because he’s the adult in this relationship.6

Strangely, Lucien’s emotional growth arc is more visible to the reader than to Sabrina. Lucien acknowledges emotional vulnerability and that he’s been going about this all wrong in a scene with his brother-in-law as they dash across Scotland to rescue Sabrina, late in the third act.

"She never will be completely docile, Lucien. She's a high-strung little filly and will always rebel," Terence warned him. "But then, that is why you love her, isn't it?" he asked, unable to see the Duke's face in the darkness, but hearing his indrawn breath at the suddenness of the remark. "You do, don't you? You've just been too stubborn to admit it."

"Not too stubborn, Terence, just too unsure of myself. I fell in love with that little vixen long ago, but by the time I realized it, I'd already committed the mistake of my life—I married Sabrina under false pretenses. Can you imagine she'd believe me if I'd told her after she remembered that I'd married her to inherit Camareigh that I'd suddenly found out that I really loved her?

“…I suppose in my inexperience [with love] I handled Sabrina wrong… I hoped she would forget the old hurts. …I’ve never been a coward about anything — at least not until then. I found I couldn’t face Sabrina.”

—Moonstruck Madness, Laurie McBain (page 382-3)

Lucien has clearly loved her because she’s not docile the entire time, but it takes him a while to figure out that loving a “high-strung little filly” means he can’t dominate or bully her into doing what he wants. He must respect both her autonomy as an adult to make her own choices, and acknowledge the validity of her emotions even if they’re inconvenient.

He knows his mistake has created a trap — he loves her but she won’t believe him, and she (inconveniently) refuses to forget what he did — but the solution (…apologizing) eludes him.

Moonstruck Madness has a lot of interesting things going on, but it doesn’t quite stick the landing, in my opinion. While the reader sees Lucien’s emotional vulnerability and understands his regret, his apology to Sabrina feels rushed and anticlimactic.

In the final scene, the lovers reunite after Lucien saves her from a random villain. Sabrina shows her soft belly first, saying to hell with wasting time not being together — she loves him! Lucien finally — on the literal final page — asks for forgiveness:

“I love you, Sabrina, and I will not live without you. Do you think you can find it in your heart to forgive me?” he asked gravely, his eyes clinging to hers, waiting for an answer.

—Moonstruck Madness, Laurie McBain (page 396)

The evolution of the romance genre has refined the expectation in readers for more extensive groveling, that’s for sure, but in combination with the earlier scene with Terence, Lucien’s emotional growth is legible to the reader and we understand that this was the true impediment to their happily ever after, not Sabrina letting go of her “childishness” to become a “woman.”

The accusation that Sabrina is a child, not a woman, says more about Lucien’s own stunted emotional maturity. By accessing and integrating more feminine-coded traits, such as emotional vulnerability, flexibility, and submission (by allowing her emotional needs to be important), in addition to his pre-existing masculine-coded traits, Lucien achieves his own ascendancy into psychological androgyne.

Sabrina may be considered a brat by the culture at large as a result of being a woman displaying both masculine- and feminine-coded traits, but the happily ever after is achieved when both the reader and the hero no longer see her as a badly-behaved child.

Gender all the way down

Gender is a central theme in Moonstruck Madness by Laurie McBain, and a central theme in scholarship about romance, including The Romance Revolution by Carol Thurston, which focuses on gender as the primary lens through which it studied books like Moonstruck Madness and its readers.

Moonstruck Madness was published 47 years ago, and Thurston’s book was published 37 years ago — yet I don’t feel the discourse in and about romance novels has strayed far from these shores.

Could it be that we keep coming back to gender because the romance genre is about gender all the way down?

In my next post, I’ll finally get to the bottom of this question, and why it’s so hard to understand ourselves through our desires.7

A few other posts on the web about Laurie McBain and Moonstruck Madness that you may enjoy:

Sweet Savage Flame Review of Moonstruck Madness - SSF is a great resource for anyone interested in vintage romance.

Laurie McBain: Revisiting the career of a bestselling historical romance writer

McBain was one of the original “Avon Ladies” — the moniker given to the authors discovered and published by Avon editor Nancy Coffey following on the success of Kathleen Woodiwiss.

Ug, yeah, it’s weird that she’s 17 at the start of her relationship with Lucien. I don’t think his age is ever mentioned but I believe he’s in his early 30s. This feels like one of those books where the age is slapped on as a convention of the genre, even though she doesn’t ever act 17, in my opinion.

…hehe. Ran her through with his sword…

It felt a bit gratuitous to include the entire exchange here, but it’s so fun, so here it is:

The Dowager Duchess nodded her head thoughtfully,

"You may not believe it now, for obviously the angers are still burning hotly, but some day this will be a good marriage. You take my word for it. You both have spirit and passionate natures, but my only worry is that you will kill each other off first. Please don't, at least not until after the birth of my great-grandson."

"Never fear, Grandmère, Sabrina is a survivor. She may look delicate and demure, but don't let her refined demeanor fool you, she's as tough as leather beneath her velvet and lace."

The Duchess smiled, thoroughly enjoying herself."

Later, Bem went on to recategorize the former “feminine”-coded traits as “expressive” and the “masculine”-coded traits as “instrumental.” To me, this sounds very similar to how the Stereotype Content Model (Susan Fiske, et. al) categorizes stereotyped groups as having either high or low warmth (social cooperation) and competence (ability to follow through on intention). I’ve leveraged Stereotype Content Model to talk about stereotypes about romance readers.

Ironically, he is the only legal adult in the marriage. I think she’s still 17 when they marry, although she’s 18 at this point in the novel. I am not a legal scholar, but some light Googling suggests that the age of majority at this time in England was 21, meaning even at 18 Sabrina was not considered an adult who could consent to marriage without her father’s approval.

Overpromise, underdeliver.

wow wow wow, I *love* the level of analysis and detail that went into this essay! kudos! IMO the romance genre gets overlooked because 1)misogyny 2)the formulaic arcs. But the best romance stories dramatize the complications of how two complex, individual characters can possibly come together, equally & amorously. This is difficult stuff (!!). I wouldn't say gender is the "main" component of conflict in romance novels, but since we live in a society where power is stratified by gender, of course it comes up frequently as a thematic obstacle/learning opportunity for many characters.

(Aside: I would be happy to recommend some queer romances where gender is secondary/unimportant to the plot.)

This is such an interesting topic and post, Andrea! ♡ I'm kind of curious about your thoughts on the emergence and inclination toward more gender-essentialist worldbuilding and dynamics in more recent romances (mostly of the fantasy variety, though some contemporaries seem to be dipping their toes I this too), because in my mind it feels like an evolution of this "gender all the way down" concept you're touching on. If it's gender all the way down, then heightening that and taking it to fantastical biological extremes kind of makes sense to me, at least in theory, though I don't know that it's always (or even often) done intentionally.

I also found myself nodding along to your mention of male grovelling being something readers have sort of grown to want -- it is something I have actually come to dislike because I feel like it's less interested these days in engaging with the gendered expectations it perhaps emerged from. What it's more interested in or what it's actually in service of, I can't say (and this very well could be just a me thing!) but I tend to come away from it feeling like it's done to an unhealthy degree, which then makes me wonder at the security of their Happy For Now 😂