Whelmed by Romance Scholarship in Europe

I am overcome by scholarship, but here's one thing to read

I set out to write a follow up to The Romance Reader's Guide to Romance Scholarship: Part 1 and found myself completely whelmed. I assume this was a result of having recently returned from Europe.

To answer the eternal question posed by Chastity in 10 Things I Hate About You (a film I’ve spoken on at length), “can you ever just be whelmed?”

The answer is yes: whelmed can be used interchangeably with overwhelmed.

I flew across the Atlantic in order to attend and present at the International Association for the Study of Popular Romance’s 2023 conference in Birmingham, UK.

(It was an amazing experience that I will fully recap later — there will be an audio/podcast component as well, as I had the privilege of capturing the voices of attendees.)

What is Romance Scholarship 102?

You’d think that with visions of romance scholars dancing in my head (Radway, Regis, and Russ, oh my!) I’d be more ready than ever to share recommendations for Romance Scholarship 102.

Alas, no.

Having recently gorged on the delectable scholarship of so many, I find my eyes bigger than my stomach for the task at hand.

With full awareness that I am in charge of the rules, I’m empowering myself to reframe the prompt.

What follows is not Romance Scholarship 102: it’s just romance scholarship I’d like to share, loosely organized. And it’s just one thing, because turns out that’s all it takes to inspire lots of thoughts.

Romance Scholarship I’d Like To Share

What Do Critics Owe the Romance?

What Do Critics Owe the Romance? Keynote Address at the Second Annual Conference of the International Association for the Study of Popular Romance

by Pamela Regis

Pamela Regis is most famous in romance scholarship for writing A Natural History of the Romance Novel (2003), and this keynote address from 2011 provides a great overview of major works of romance scholarship up until this point.

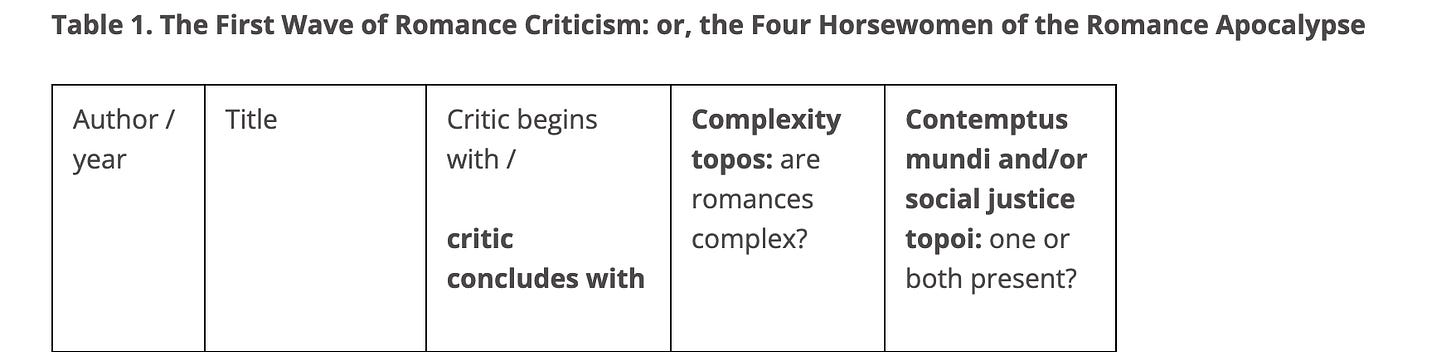

As someone who loves structure, I appreciated the tables and method of organizing her analysis.

I read this a while ago when I was first dipping my toes in to scholarship, and it helped me organize my own thoughts about the texts that Regis covers.

Upon re-reading it this week, I found myself ready to object to some of analysis in the first half.

Minutes before, I had read a persuasive response to the keynote from An Goris, Matricide in Romance Scholarship? Response to Pamela Regis’ Keynote Address,1 which points out that Regis’s literary historical approach (like all approaches) “is one which highlights certain aspects and disregards others.”

However, once I got to the latter half of the keynote, I discovered a new, deeper appreciation for how Regis answers the question: “What do critics owe the romance?”

For example:

“We owe it to the romance novel to make overt and to defend our conclusion that the romance is simple, if this is, in fact, our assessment.”

I had just been talking about this with a few fellow IASPR conference attendees on the Discord! The question “are romance texts complex or simple?” is still one that’s alive and well in modern romance discourse.

At the end of the day, I don’t think romance needs to be complex to be worthy of study, and the desire for it to be seen as complex seems like a defensiveness against a systemic prejudice that says that texts must be complex in some “literary” way to justify its study.

“We owe it to the romance novel to recognize that our study texts are probably not representative of “the romance” and to stop committing the logical fallacy known as hasty generalization.”

Regis is speaking here about making generalizations about the entire genre based on a small body of texts (usually along with the indication or implication that any selection would do because they’re all the same), but it also makes me think about a personal pet peeve of mine:

I think there’s a tendency for scholars with literature backgrounds to gravitate to and study romance texts that adhere closely to “literary” markers of quality or are “less problematic,” which means that a lot of close reading is being done on romance novels that aren’t representative of “most” romance.

This can end up elevating texts that are outliers to overrepresent the genre and reinforces “literary” standards as the correct ruler to measures romance success.

It also centers what the scholar values instead of what the audience values. I wrote about this recently, so maybe this is just top of mind for me:

Does Colleen Hoover Write Romance?

When does one become a Real Romance Reader, and not just a reader of romance? Two recent incidents prompted this question. The first was an episode recording about The Flame and The Flower this weekend…

And, Regis recognized this danger, too:

“We owe it to the romance novel to recognize that the values of its fans are not identical with the values of our discourse community.”

…and the corollary to the point above about hasty generalization:

“We owe it to the romance to stay within our evidence when we state conclusions. So, if we have not demonstrated that our study texts are representative, we must qualify our conclusions, and avoid talk about what “the romance novel” writ large is or does.”

I’m a weirdo in that I am VERY aware of overstated conclusions, especially correlation masquerading as causation…

Exhibit One:

…and yet I’m also guilty of making grand claims about romance writ large based on anecdotal evidence and my gut, with probably not enough qualifications. (“Not ALL romance obviously!”)

It’s too easy to shrug this off as “I am complex! I contain multitudes!” I’m a hypocrite, OK? Do as I say: not what I do.

For example: do yourself a favor and read Regis’s keynote and see what thoughts and ideas it inspires for you!

Read: What Do Critics Owe the Romance?

I think An Goris’s response is also really thought-provoking! I am still thinking about how Goris’s response — which, again, I found persuasive — impacts my reading of Regis’s keynote.