Becoming Desirable: Transformation vs. Makeovers in Romance

Why I'm still thinking about The Charm School by Susan Wiggs

I first read The Charm School by Susan Wiggs when it came out in 1999, and I don’t think a year has gone by since when I don’t think about it.

Back then, I was a teen who haunted the library, paying close attention to new releases in the “new fiction” rack at the front of the adult library room. I’d often take home 10-15 books, mostly romance novels.

The stories I devoured in every free minute allowed me to both cope with the authoritarian household I was stuck in, as well as fantasize about my escape plan by imagining ways of being that were not accessible or modeled to me in my lived experience.

Fairy tale retellings were irresistible to me (unsurprisingly), and The Charm School was one of a few historical romances that Wiggs published at the time that played with fairy tale motifs. The Charm School was a play on the Ugly Duckling tale1, and The Firebrand explored the Beauty and the Beast motif. Maybe she also wrote others, but these are the two that have stuck with me through the years.

I first understood The Charm School as a “makeover” story, and while I understand why that fantasy would be particularly appealing to me as a young person, over time I started to worry that it was a harmful fantasy.

I won’t bury the lead: I have come to the conclusion that The Charm School is actually a transformation story, and that there’s an important distinction between makeovers and transformations.2

Let’s talk about it.

The Charm School

The Charm School is about Isadora Peabody, a wealthy bespectacled bookworm who feels out of place in Boston society and in her accomplished family. It’s 1851 — she’s supposed to be focusing on finding a suitable husband, not learning new languages and vocally supporting abolition.

Isadora is described as an Ugly Duckling, which is even more stark given she’s embedded in a family of Beautiful People:

Peering over the thick lenses of her rimless spectacles, she saw herself for exactly what she was. Her hair was the color of a mud puddle. Her eyes lacked the pure clear blue so prized by her parents and so evident in her siblings. She had none of the gifts of laughter and beauty her brothers and sisters possessed in such abundance…

[Isadora was] dark where the others were fair, pallid where the others were fashionably pale, round where the others were angular, tall where the others were petite.

Isadora is hopelessly in love with Chad Easterbrook, the handsome and vapid son of a prominent Boston shipping family. Too bad he is completely oblivious and uninterested.

Isadora’s life is pretty bleak, despite her family’s wealth and social privilege. She’s an outcast who can’t just opt out, forced to endure cruelty from her peers and siblings, pity and disapproval from her parents, with no friends or confidants to provide relief from the constant barrage.

At a society party, Chad’s father tells Isadora that one of his ships, The Silver Swan, has just made record time and record profits under the helm of brash Southerner, sea captain Ryan Calhoun.

Ryan is the black sheep of his own family, but for different reasons: born into a wealthy Southern family that enslaved people, he rejected their way of life by attending Harvard and as soon as they were in the North, freeing Journey, his childhood friend.

Ryan’s ship has earned Mr. Easterbrook a tidy sum, but Calhoun is also a little outrageous and unconventional, and has returned to shore without a translator and navigator. Mr. Easterbrook threatens to not hire Ryan for the next journey if he can’t shape up and find a replacement.

Isadora is in a dark place after a steady stream of humiliations. She remembers how her Aunt Button, the one family member who loved and appreciated her for her true self, taught her to lead with her strengths, and also taught her to dream of adventure. Their favorite destination to read about was Rio de Janeiro, which just so happens to be the destination of Easterbrook’s ship’s next journey.

And so, Isadora finagles her way onto Ryan Calhoun’s ship as the newest member of his motley crew, serving in the role of translator and navigator — the true selling point, though, is she promises to report back to Mr. Easterbrook about Ryan’s activities, which he quickly figures out.

As soon as they are at sea, Isadora’s transformation begins: on a ship full of outcasts, she thrives. Free from social censure, her curiosity and openness earns her friends eager to teach her to tie knots, climb rigging, dance on a ship deck, and most of all, she begins to learn self-confidence.

Ryan has secrets related to ship activities that he must protect, and so at first he’s wary and hostile towards Isadora. Yet, he still finds himself drawn to her and recognizes her as a kindred spirit who has coped differently with not fitting in.

Isadora’s transformation happens steadily and organically. She set out on the journey to simply escape, not to Eat. Pray. Love. her way across the Atlantic. Her relationship with Ryan is important, but the sum of the impact of her other relationships have an even greater impact as she recognizes that she was not the problem: she was a fish who’d been living out of water.

She recognizes that she was not the problem: she was a fish who’d been living out of water.

Her physical transformation results from being happy, from being with people who love her as she is, and from worrying less about social rules, not more.

Yes, Ryan throws her spectacles overboard — but he’s learned she sees better without them and she’s only wearing them because her mother worried she’d hurt her eyes with too much reading.

For 200 pages of the book and months of her journey, she doesn’t look in a mirror, and while we get hints about her physical transformation through Ryan’s observations, his love for her is clearly unrelated to her beauty.

When she does finally see herself in a full-length mirror upon her return to Boston, she is stunned by how her internal transformation has also emerged as a physical transformation:

The ugly duckling had become a swan.

She wasn’t pudgy and pale, but fit and strong, thanks to the Doctor’s galley rations and an active life on shipboard. A mass of sun-gilt curls framed her astonished, almost elegant-looking face. Sun and wind had turned her pallor to a vivid gold hue, unconventional yet curiously attractive. The daring dress and dancing shoes completed the picture of a bold beauty, unknowingly transformed in ways she knew went far deeper than looks alone. She realized that it was not so much her looks but her very deepest inner self that had changed.

The Transformation as an Empowering Tale

While Isadora is physically transformed, she has not transformed into the pale, delicate, and petite model of physical desirability she used to compare herself to. She has transformed into the external manifestation of her inner self, which is a version of beauty for which she had no reference.

While Boston society is drawn to her transformed appearance, she knows she still does not conform to the requirements for social desirability but as a result of her transformation, she no longer cares. For example, she’s become an even more vocal and active abolitionist, and after spending months aboard a ship, she’s still too unconventional to be the perfect society miss.

When Chad proposes, it becomes crystal clear the things she thought she wanted had no meaning. She didn’t love Chad because she didn’t know Chad: he represented a fantasy of love and acceptance by people in the only world she knew.

The Charm School is a story about Isadora transforming into her true self, and love and acceptance created the environment under which she could begin that transformation.

Transformation vs. Makeover

Transformation stories are about identity and becoming desirable, but so are makeover stories. In romance stories, both types of stories often explore which aspects of identity are desirable and which are undesirable, and provide models for the audience.

In my opinion, there’s a difference between a transformation and a makeover, and these differences are important mediating factors when it comes to the impact of the narrative arc on readers.

Transformations begin with an internal change/action, and those changes result in external changes that others can observe and respond to.

Makeovers begin with an external change/action, which causes others to respond differently, resulting (supposedly) in an internal change.

To illustrate the differences, I’d like to bring in a second piece of “romantic” media that came out the same year as The Charm School to illustrate makeover story arcs: She’s All That.

Social Desirability: Becoming the Prom Queen

She’s All That is a Pygmalion-inspired teen romcom that came out in January 1999.3

The inciting incident of the story begins when super cool high school jock Zack (Freddie Prinze Jr.) faces public humiliation when he is dumped by high school it-girl Taylor Vaughn.

Why is Zack so peeved? He doesn’t seem to care about Taylor all that much, rather he cares about what she represents: he must possess the coolest girl in school to maintain his social position as the coolest guy in school.

Bruised from the loss of his social equal mate, Zack boasts to his pals Paul Walker and Preston that Taylor’s desirability is an illusion:

“Strip away all that attitude and make-up, and basically all you have is a C-minus GPA with a Wonder Bra.”

Paul Walker proposes a bet, and Zack agrees. The terms? Paul picks the girl, and Zack has six weeks to turn her into the prom queen.

Passing over girls who are, in order, blowing bubbles4, “fat,” and picking a wedgie, Paul Walker gleefully finds the most helpless case of all: Laney Boggs.

Zack protests:

“Fat I can handle. Weird boobs, bad personality, maybe some sort of fungus. Scary and inaccessible is another story.”

Laney proves just how scary she is by being singularly unimpressed and dismissive of Zack’s attempts to initiate contact, especially since his smooth moves include acknowledging her brother by calling him a name that is not only NOT his name, but also an ableist slur!

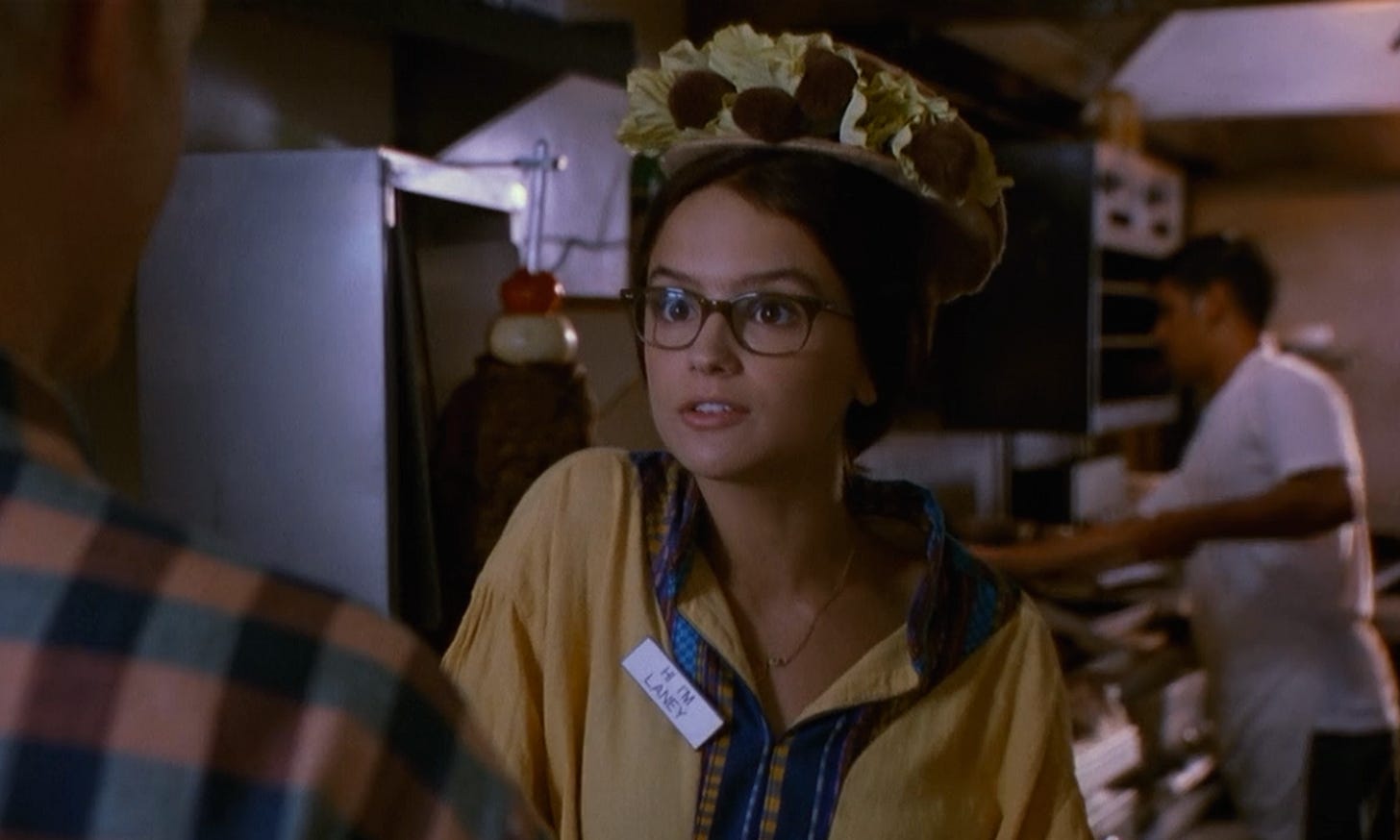

As we get to know our protagonist Laney (Rachael Leigh Cook), we learn she is totally fine being a weirdo art kid whose fashion choices are limited by financial resources, practicality, and lack of desire to dress for the popular kid gaze.

Is Laney unattractive and unfashionable or is she just a lower-middle-class teen with a part-time job who needs to apply herself to her chosen profession if she wants to get a scholarship to go to art school?

(Spoiler: it’s the latter, but this movie thinks it’s the former.)

There’s an attempt to frame Laney’s choices and indifference to fitting in as “a problem”: she can’t create great art because she’s so focused on intellectualizing meaning instead of expressing her authentic inner self. Does she need to care more about what the popular kids at school think about her, or does she need therapy to deal with her mother’s death?

(Spoiler: it’s the latter, but this movie thinks it’s the former.)

Zack’s dogged determination to spend time with Laney and coach her on social desirability leads to scenes where he shares his wisdom on being a socially-desirable woman:

“Would it hurt you to smile once in a while?”

“Forget CNN!”

“You ever think about contacts? Because your eyes are really... beautiful.”

“Hack. Y. Sack.”5

Laney is a reluctant participant in her makeover, however Zack has a bet to win and he knows just how to win it: abuse his power as high school royalty by pressing the junior varsity soccer team into service taking over Laney’s oppressive domestic duties while he relaxes on the couch and have his make-up obsessed younger sister Mac (Anna Paquin) come over, tweeze Laney’s eyebrows, give her a haircut, remove her glasses, and pour her into a slinky red dress that displays her bangin’ bod.

When the romantic acoustic strains of Sixpence None The Richer’s “Kiss Me” waft in, you know that this is a turning point in the relationship between Zack and Laney. He may have been appreciating her personality a little bit before, but suddenly he’s aware of her as a sexually (and socially) desirable partner.6

When Laney transforms into a socially desirable romantic partner, she is no longer treated with contempt — she becomes an object to possess, and therefore someone to be envied.

Exhibit 1: Envied for possessing powerful male attention.

Exhibit 2: Envied for authentic creative expression.

The Makeover as Cautionary Tale

Makeover stories are usually cautionary tales: stick with the people who appreciated your “true self” and not just your “hot self.”

“I made that bet before I really knew you, Laney,” Zack says.

These messages are usually undercut by an ending where the made-over character (usually a woman, quelle surprise) retains the most impactful aspects of the physical makeover, even if she ends up integrating aspects of her true self into her appearance and thus creating a more “authentic” version of her fashionable self.

Even once Zack realizes his bet (and his friendship with Paul Walker, character name irrelevant) was shallow, and he pays the price of losing by walking his graduation ceremony naked7, when he throws that soccer ball that was preserving his modesty Laney’s glasses are long gone and she’s noticeably “hotter” than she was in her quirky art kid drag.

I guess she got over her distaste of touching her eyeballs every day so that men can better appreciate her beautiful eyes.

In She’s All That, experiencing social desirability is mostly positive for Laney. She enjoys being acknowledged by people who wouldn’t give her the time of day before, although she learns that being visible incites envy from jealous haters. Social desirability still has value, even if the audience understands that certain people’s opinions don’t and shouldn’t matter to Laney.

Look, I still love She’s All That: it’s entertaining, and it does have some interesting social commentary embedded within it. Nonetheless, Laney’s makeover is both deeply pleasurable and messy when you stop to consider the ultimate message for the audience.

The Pleasures of Change

I think the idea that transformations or makeovers are harmful stems from the idea that we should be loved for who we are, and that we don’t need to change. Our culture bombards us with non-stop messages telling us we should change, and here’s what you should be, and here’s what you should do to make it happen.

Yet, because of those cultural messages, there is pleasure to be found in a fantasy where we can change.

There is also tension with our inherent desire to be loved as we are, and to have been good enough all along.

The Ugly Duckling is a story about a swan raised among ducklings, in a social environment in which one is measured against the wrong indicators of value.

The titular character was an ugly duckling, but a beautiful swan. The conflict was one of perspective and categorization, and how that impacts one’s own sense of identity.

By changing perspective, the ugly duckling is able to transform effortlessly.

The Fantasy of Acceptance

The Charm School is a meditation on acceptance. Wouldn’t it be lovely to have been good enough all along?

I want to transform, yet be myself.

Love me for who I am, and I will be able to let go of the things that hold me back. Accept me even if I don’t change to fit in.

Aboard The Silver Swan, there exists a fantasy space where we can become the true self we were all along, and oh, it’s beautiful.

I have been working on this on and off for a month — at some point I had to make the decision to stop having so much fun describing She’s All That and finding the perfect screen shots because the point was to talk about The Charm School!

There’s actually a lot more to say about The Charm School, especially when it comes to how it handles discussions of slavery, the North’s complicity in profiting from enslavement in the South, and how central abolition and freeing/reuniting one particular family was to the plot of the book.

I hope to circle back in the future and discuss this in the context of historical romance!

“Ugly Duckling” fairy tale was first written by Hans Christian Andersen in 1843.

I know this sounds like a convenient reframing, but in this case, I think the simple conclusion was actually concealing a more interesting answer.

Catherine Coulter, on the cover quote for the original version of The Charm School, says that it’s a blend between The Ugly Duckling and My Fair Lady. MFL has its roots in the Pygmalion story. I don’t think The Charm School actually has a Pygmalion element, so I respectfully disagree with Coulter on this one.

To this day, not sure what socially-undesirable trait blowing bubbles reveals.

I choose to believe that the “never let it drop!” hacky sack routine is actually about the unrealistic societal expectations placed on women to always be perfect, and not just about Zack’s individual circumstance of a disapproving dad.

Is it coincidence that the venn diagram of sexual and social desirability is a circle? Discuss…

As far as bets go, I suppose this one is supposed to be humiliating (in the movie world) rather than jail time for public indecency (in the real world). Given everyone seems to appreciate Zack’s banging soccer bod, it’s a final example that shows how poorly-conceived Paul Walker’s terms were. And yes, I refuse to look up Paul Walker’s character’s name. 2 Late, 2 Lazy, Rest in Peace my blond surfer Adonis.

I am definitely going to read this book! This is so fascinating to think through. As a lover of strong internal arcs, it's no surprise that I would also love transformation stories. That also fits in with my former social work career. The makeover story is a strong fantasy but it doesn't have any power if it isn't paired with inward transformation.

Love this! The contrast between transforming to conform to society’s desirable standards vs transforming to become more true to yourself is really interesting.